Monday, Dec 06, 2021

RISK-BASED SUPERVISION OF CROSS BORDER GROUPS

DECEMBER 2021

INTRODUCTION[1]

Toronto Centre has consistently promoted risk-based supervision (RBS) as the most efficient and effective approach for financial supervisors [2]. The starting point in RBS is a thorough and detailed knowledge of individual supervised firms - the business they are doing, their control and management structures, and their financial resources. Where an individual firm is part of a wider group it is necessary to establish a similar level of understanding about the group as a whole. This enables the supervisor to develop a comprehensive understanding of potential risks and to intervene to require the firm to address them.

Explanations and illustrations of RBS tend, for reasons of simplicity, to be set in the context of a single institution in a single jurisdiction undertaking a single activity – often banking or insurance. In reality, however, supervisors are often faced with more complex structures.

- Many financial firms operate cross border. Such operations may be relatively straightforward involving branches, or more complex involving a range of structures such as subsidiaries and joint ventures.

- Many firms also operate as conglomerates – either within their home jurisdiction or cross border. Conglomerates are defined as groups of companies under common control or dominant influence, including financial holding companies, which conduct material activities in at least two of the banking, securities or insurance sectors. Some conglomerates also include non-financial entities or entities which undertake financial activities but are not regulated in some or any of the jurisdictions in which they operate. Toronto Centre and others have published extensive material on the supervision of conglomerates [3]. This Toronto Centre Note examines the issues involved in the supervision of cross border financial firms including conglomerates and sets out some principles that supervisors should follow when faced with such structures.

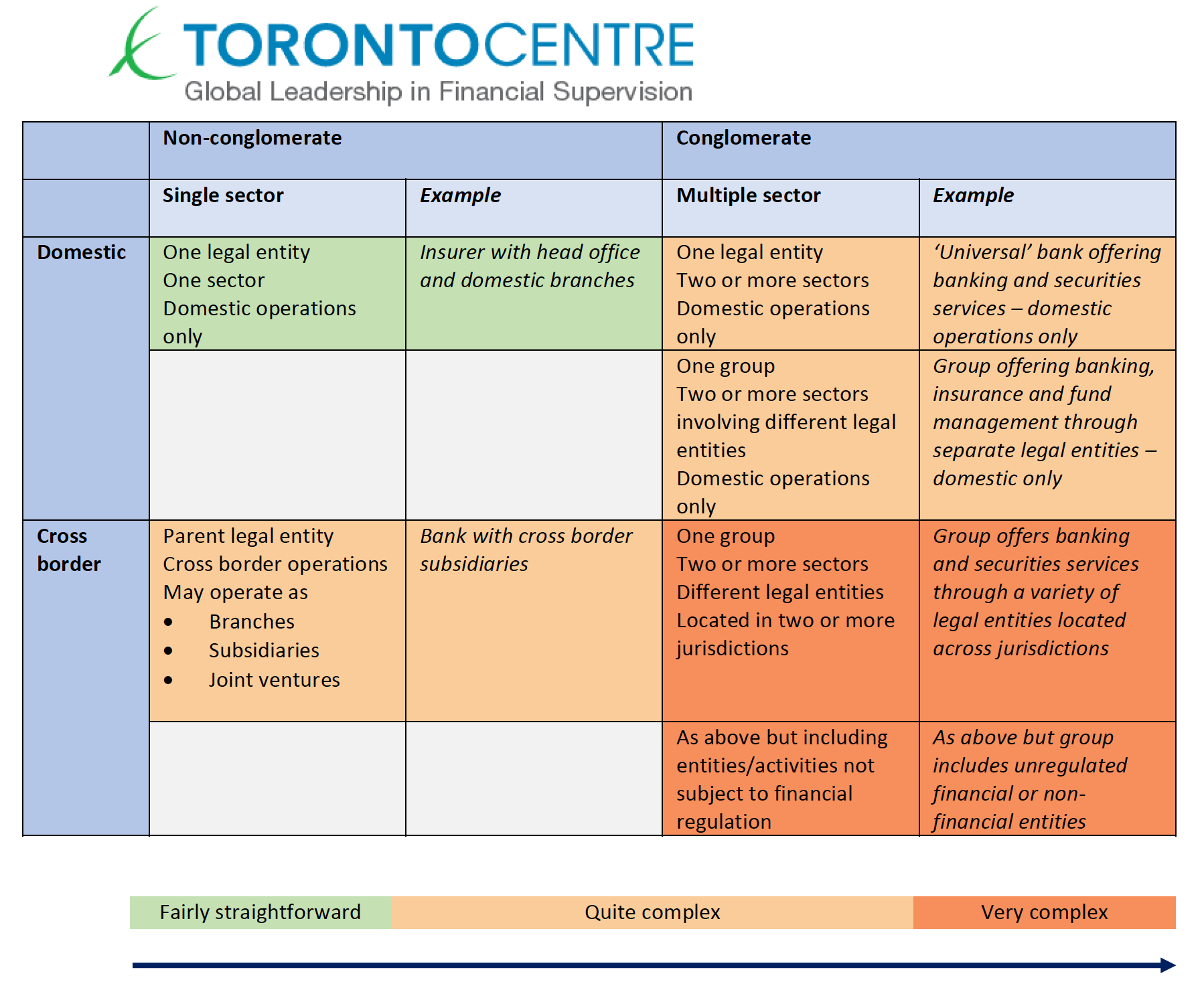

Levels of complexity

The table below illustrates how the supervisory challenge increases as firms’ structures become more complex. The complexity is greatest where conglomerates operate across national borders and is compounded where the nature or extent of regulation differs markedly in the countries or sectors involved, or where a group contains entities that are not subject to financial regulation at all.

The extent to which firms are able to put in place complex structures will, in practice, depend on legal and regulatory constraints which, in the case of cross border groups, may be imposed by home or host authorities. Firms in some jurisdiction may not be allowed to offer products from different sectors at all, while others may be allowed to do so but with restrictions on the legal structures involved.

Complex structures pose a challenge for both conduct and prudential supervision. In practice, conduct supervision (aimed at avoiding harm to consumers of financial services from firms’ misconduct) tends to be a host country responsibility. However, in carrying out this responsibility host supervisors will need to take a close interest in group-wide culture and controls over areas such as sales practices.

However complex the structure and operations of a financial firm or group, the aims of risk-based supervision remain the same. These are to have a full understanding of the risks being run by the supervised entity or group of which it is part and how well these are controlled. Supervisors also need to assess the adequacy of financial resources. In some cases supervisors may judge that the group is too large or complex to be effectively managed or supervised. The over-arching purpose of this supervisory activity is to support timely and effective intervention to address significant risks. In the case of firms or groups with cross border activities this will require collaboration with others.

Corporate structures: single sector (non-conglomerate)

This section looks at the commonest structures for cross border activity. For purposes of simplicity it examines these from the point of view of firms operating in only one sector. In practice many firms or groups operate across borders in multiple sectors, making them cross border conglomerates. These are looked at in a later section.

Branches

Supervisors are very familiar with the idea that financial firms operate through branch networks within their jurisdictions. From a legal, financial and governance standpoint, branches are effectively indistinguishable from the parent firm:

- Branches have no separate legal ‘personality’ but are part of the same legal entity as the parent. Anyone entering into litigation for example would not normally take legal action against a branch but against the parent institution.

- While there may be some local responsibility for minor financial issues such as operating expenses, branches have no separate financial standing. Funds deposited with a bank branch or contracts entered into with an insurance branch directly impact the parent institution’s balance sheet. Branches accordingly do not have meaningful balance sheets of their own and neither do they hold capital. They will implement controls such as customer take-on procedures; lending, underwriting or transactions limits; and anti-money laundering checks; all of which are necessary to preserve the integrity of the parent balance sheet. But these control mechanisms will be developed and monitored centrally.

- Branches will have their own ‘local’ management structures – such as a branch manager for example – but aside from this they are subject to the high-level control, management and governance arrangements in the parent. The controls they operate are centrally devised and monitored; they are subject to firm-wide high-level control structures (such as risk management and internal audit); and they do not have their own senior managements or boards.

Similar broad principles apply to cross border branches as to domestic ones. The ‘host’ supervisor in which the branch is situated may have some local responsibilities – for example in respect of conduct issues, controls over financial crime or in some cases liquidity [4]. Some host supervisors also impose asset maintenance requirements –a requirement that funds are held in the host jurisdiction equivalent to a proportion of the branch’s liabilities. These funds play a similar role to local capital but beyond being a proportion of its liabilities, the requirements are not generally aligned with the risks embodied in the branch’s business.

Notwithstanding any financial and other requirements that may be placed on branches it is generally not meaningful to seek to supervise a branch in isolation and the ‘home’ supervisor will include it as part of their consolidated oversight of the firm as a whole. Even in those areas for which the host supervisor retains responsibility, it is wise for it to establish close contact with the home supervisor both to share its findings - in respect of AML controls for example - and to seek a group-wide perspective on risk and control issues.

For supervisors the main risk from overseas branches arises from an ‘agency’ issue. Branches may be remote geographically and hard to monitor by both the parent institution and the home supervisor. They are nevertheless in the privileged position of making use of the parent’s balance sheet, a situation which may be abused if controls over the branch’s activities are deficient.

Subsidiaries

Subsidiaries by contrast are separate legal entities in that they are incorporated in their country of operation. This gives them an independent legal personality and means that they are subject to broadly the same financial and governance requirements as any other legal entity in the jurisdiction. They have separate balance sheets and are required to have their own management and governance arrangements [5]. Because they are distinct entities it is meaningful and necessary for the host authority to supervise subsidiaries, which are incorporated and have the same legal and accounting status as locally domiciled firms.

Notwithstanding this legal separation there remain, in reality, indissoluble links between subsidiaries and parents. Issues such as financial strength (group capital and liquidity), management and governance and reputational risk cannot be considered in isolation from the perspective of either the subsidiary or the parent. It is therefore necessary and desirable for the host supervisor to maintain close contact with the home supervisor. The interactions between subsidiaries and parents and the challenges they pose for supervisors have given rise to established approaches to consolidated and conglomerate supervision.

Branches or subsidiaries?

In some jurisdictions the nature of operations undertaken by overseas-domiciled institutions is prescribed in regulation. Some host supervisors insist that operations undertaken in their jurisdiction take the form of subsidiaries on the grounds that this gives them control over a ring-fenced local entity. Others may allow branches but on restricted terms such as a provision that the branches do not do business with retail customers.

In contrast, some other host supervisors may not allow subsidiaries at all, insisting that operations, particularly of banks, in their jurisdiction take place through branches. Even where subsidiaries are not prohibited there may be a strong preference for branches. This reflects a view that the viability of any subsidiary is, de facto, dependent on that of the parent and hence to a large extent on home country supervision so that the apparent autonomy provided by the existence of a subsidiary may, in reality, be illusory.

Where a choice of branches or subsidiaries is permitted, financial firms will choose between these on a range of (usually economic) factors such as capital efficiency or tax issues.

The importance of reputation

Subsidiaries, by dint of their legal separation from parents, are to some extent insulated from them. In theory a subsidiary could fail while the parent remained a going concern. It is also theoretically possible (but much harder to imagine) the opposite of this - the subsidiary remaining a going concern in the event of the failure of the parent.

In practice however this insulation is highly imperfect mainly because of the effects of contagion and reputational damage. This is particularly acute in the case in banking where the business model and in particular the maintenance of liquidity are critically reliant on confidence. In reality, the knowledge that ‘(parent) Bank X has failed’ may create an insurmountable loss of confidence in the overseas subsidiaries of Bank X, particularly where these have the same name. Similarly, the failure of a subsidiary of Bank X may have serious reputational repercussions for the parent. These reputational risks are also present but may be less acute in other sectors. Supervisors need to remain mindful of these limitations of subsidiary structures and of their implications.

It may be very difficult for a subsidiary to remain in business in the event of the failure of a parent. A more likely – albeit relatively positive – outcome may be that a subsidiary with a separate balance sheet and adequate self-standing capital can at least be sold (in whole as a going concern or in part) in such circumstances. Such a ‘market solution’ may reduce potential instability in the host jurisdiction.

Parent institutions may behave unpredictably in the event of subsidiaries coming under pressure. There are many recorded instances of parents stepping in to provide financial support to subsidiaries even where there was no formal or legal obligation to do so [6]. The absence of any formal obligation means that the support represents an unforeseeable but nevertheless real potential drain on the parent. This is known as ‘step in’ risk [7]. In other cases parent institutions have not, contrary to expectations, provided support to failing subsidiaries. In general both home and host supervisors should be cautious in making assumptions about potential intra-group support.

|

Other structures

Some firms operate cross border through representative offices. Where such structures are permitted it is usually on the basis that they are merely a channel for introducing customers to the firm. They are accordingly not allowed to do any business directly with customers. As such they are of little supervisory significance [8].

Other firms operate as joint ventures. An insurer in country X for example may decide to invest jointly with an insurer (or, if permitted, an entity from a different sector) in country Y in a venture designed to exploit synergies or the opportunities afforded by a larger market. Such an arrangement of any significance will usually involve the creation of subsidiaries so that the challenge for home and host supervisors is to understand fully the nature of the joint venture and, critically, its implications for the financial soundness and stability of the parent. This will depend partly on the size and nature of the parent firm’s investment.

A serious challenge for supervisors is the incursion into their jurisdiction of internet or tech-based companies which offer financial products or services without any meaningful presence in the country. Such entities may pose all the conventional risks associated with financial products – conduct risk, money laundering or financial crime and even in some cases risks to financial stability. Where the product or service being offered is regulated and therefore requires authorisation this in principle gives the host regulator some powers, although exercising these may be a challenge. In practice the host supervisor may have few or no powers to ensure that risks are effectively managed. If the provider is regulated in an identifiable home jurisdiction, the host may seek reassurance that the risks are being addressed or offer to collaborate in this. But in the absence of any direct powers, hosts may have few options other than to rely on the education of consumers in the risks involved. These problems become much more acute if the activity such as the operation of a retail payments system by a non-bank has a potential impact on supervisory objectives but is not subject to regulation in the home and/or host jurisdiction [9].

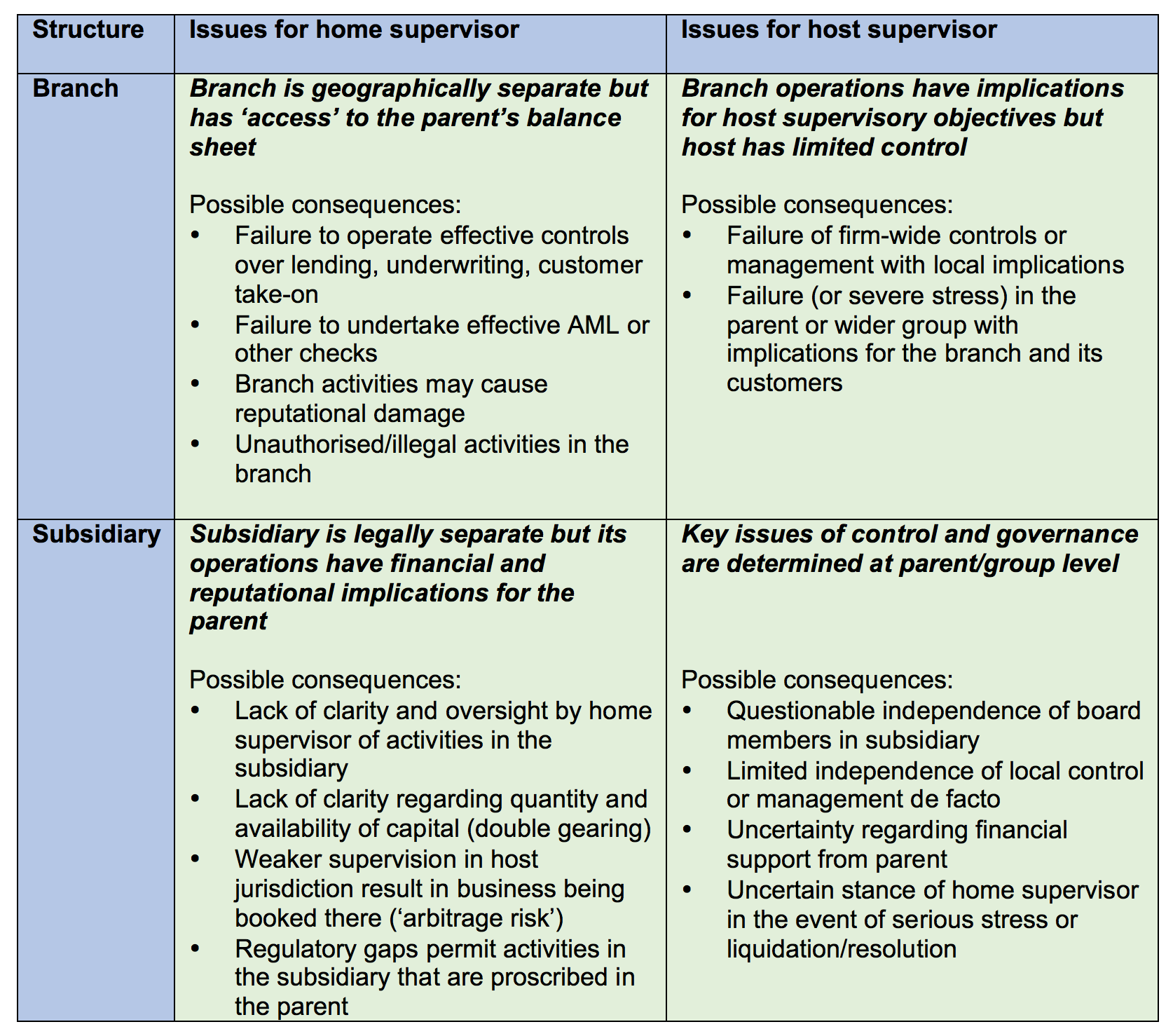

Summary of risks from cross border operations

In order to assess and ultimately to mitigate risks to their objectives, supervisors need to have a clear and thorough understanding of the firm’s business and vulnerabilities. This task is inevitably more complicated when firms operate cross border. The table summarizes some of the main issues for both home and host supervisors.

|

Consolidated supervision of cross border groups

An earlier Toronto Centre Note set out a number of issues in the consolidated supervision of international groups – that is, the development of a comprehensive oversight of groups and the risks they pose [10]. It is more difficult for home or consolidated supervisors to get a grip on the structure, activities and modus operandi of such groups than it is for wholly domestic ones. The earlier Note identified four particular types of risk associated with such groups. The first three of these can also be found in domestic groups, but they are more acute in the case of cross border ones.

- Transparency risk. It may be difficult for supervisors to understand the structure or mode of operation of a group. Home supervisors may fail to have a comprehensive oversight of the group’s financial resources and be unable to reassure themselves that capital is genuinely available when it is needed – there is no ‘double gearing’

- Contagion risk. The crystallisation of risks elsewhere in the group may compromise the stability of the parent or the group as a whole

- Autonomy risk. Boards and managements of subsidiaries may comprise individuals appointed from the parent who may lack independence and be subject to conflicts of interest

- Arbitrage risk. It may be possible for groups to exploit differences in regulatory or supervisory standards in different jurisdictions in which they are active. In some cases activities in host countries may be unregulated, creating a risk of ‘dark corners’ [11].

Cross border operations also raise potentially difficult issues of ‘mind and management’. Supervisors must be able to identify where the key drivers of strategy, management and direction in a group are located and which individuals are involved. The expectation is that these will typically be located in the parent firm or head office, but this may not always be the case where groups undertake cross border activities and the true location may in practice be hard to discern. The drivers of a specific business activity may sometimes be located outside the home jurisdiction, particularly if that activity is not undertaken in the home country. In some extreme cases a group’s whole de facto mind and management may be located outside of the home jurisdiction.

There may also be issues of the suitability of a cross border firm’s controllers or managers. Most supervisors require controllers of financial firms to be approved subject to ‘fit and proper’ requirements but are familiar with the potential problem of control actually being exerted by persons or institutions who may have no formal standing in respect of the group and are therefore not captured by the usual arrangements. This potential problem is compounded in the case of cross border groups.

These and other challenges underline the importance of information sharing and coordination among home and host supervisors, all of whom will have specific or local knowledge that can be used to build up a more complete picture of the cross border group and its operations than will be available to any individual supervisor.

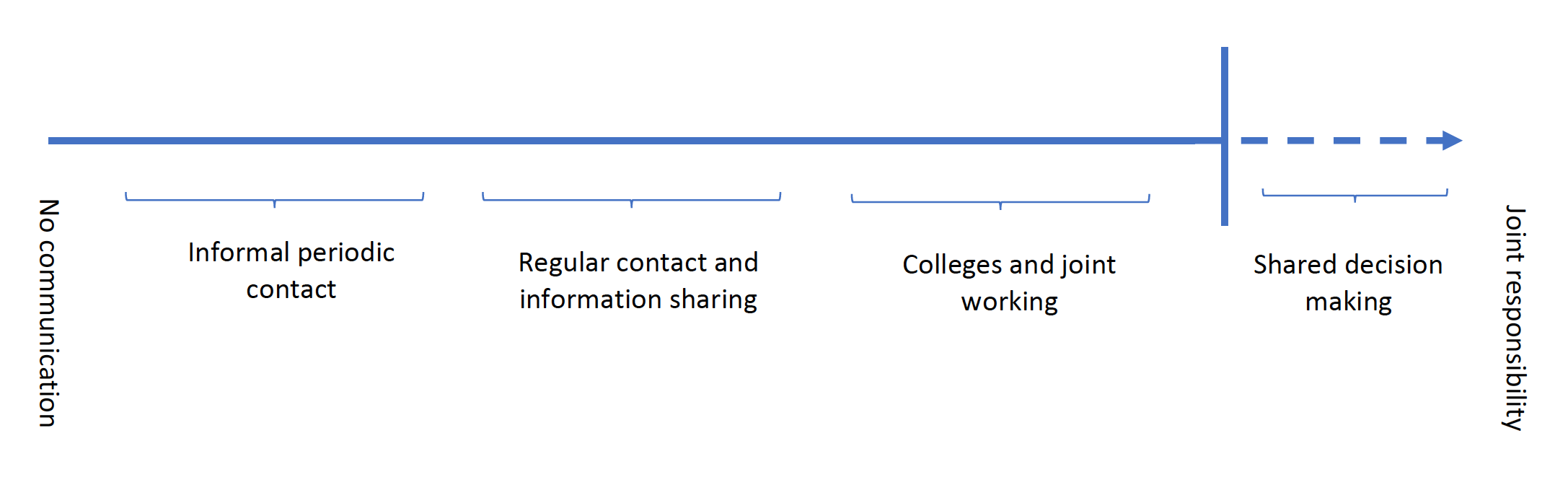

Supervisory collaboration

Effective communication between home and host supervisors is key to understanding the totality of a firm’s cross border activities, and to identifying and mitigating the risks it is running. While this may appear self-evident, there are cases in which even rudimentary contact does not take place.

The following diagram outlines the stages in supervisory collaboration.

- Even informal periodic contact represents an immeasurable improvement on no communication at all. Supervisors should aim to get to know the relevant staff, at all levels, who are engaged in the supervision of their firms in counterpart organizations. This may involve no more than picking up the phone or sending an email which may be a pre-cursor to video or (Covid permitting) a face-to-face meeting. While these points are rather obvious, they are worth making because some supervisors (home and host) do not, for whatever reasons, undertake even this basic level of contact.

- A natural evolution from this informal contact is the establishment of more regular contacts – perhaps quarterly or annually – between home and host supervisors. These may simply involve a discussion of ‘top of mind’ issues in respect of the firm involved. At this point the supervisors may wish to consider the arrangements underlying the sharing of information.

o Much supervisory information tends, in its nature, to be confidential. Supervisors should establish legal ‘gateways’ which enable them to share information for legitimate supervisory purposes. If such provisions do not exist in the legislation underpinning supervision they should be introduced as a matter of priority.

o Many supervisors will at this point wish to consider introducing memoranda of understanding (MoUs) to place information exchanges on a more regular footing. MoUs have significant limitations. They have no legal force and neither place an obligation on parties to share information nor give them ‘rights’ in terms of seeking it [12]. Notwithstanding these limitations MoUs are surprisingly useful as a statement of intent to share information and as an aide memoire concerning the type and nature of information to be shared – including in some cases confidential material where supervisors are willing and able to provide it.

- More formal arrangements for sharing information and perspectives on risk are supervisory colleges. These are permanent but flexible groups of (home and host) supervisors with an interest in a particular firm or group who meet on a regular basis to discuss developments. These are discussed in detail below.

- Colleges should also promote joint working where supervisors either share information – for example on supervisory assessments – or undertake joint visits. A straightforward version of this is where a home supervisor is visiting an overseas branch or subsidiary and invites the host supervisor to join the visit. A less common version is where a home supervisor invites a host supervisor to join in a supervisory visit to the parent. Because the scope of such visits may go much wider than the firm’s overseas operations this may raise some issues of confidentiality and ‘need to know’. In practice however it is possible to overcome such problems if the will exists to do so.

- For completeness it is worth considering the most ‘extreme’ version of cross border collaboration – shared or joint responsibility. Most supervisors will have very limited scope for doing this. The legislation underpinning supervision requires national supervisory bodies to undertake necessary supervisory tasks. Joint working or information exchange can support national supervisors in doing this through allowing better informed decision making. It is also possible – and generally desirable – for supervision to be coordinated so that the separate and independent actions of supervisors can be consistent and mutually reinforcing. But none of this can supplant national responsibilities. Supervisory decisions and actions can only be taken nationally; they cannot be shared or delegated and national authorities are accountable for them. Only in the most unusual circumstances – typically where supervision is undertaken by a supra-national body (as is the case for major institutions in the EU) – can national authority be subsumed in this way.

Operation of supervisory colleges

Colleges exist to promote information exchange and cooperation/collaboration among supervisors. They should aim to develop a common understanding of the risks in internationally active groups, agreement on any necessary supervisory intervention and a degree of coordination and consistency in implementing this They also provide a platform for communicating consistent supervisory messages both among college members and to the group.

They are permanent but flexible structures whose leadership, composition and agendas need to reflect the size and complexity of the group on which they are focused and which can be adjusted as circumstances change. It will normally fall to the home supervisor to convene colleges, determine the agenda and coordinate any follow up work.

In order to achieve the necessary level of oversight, college members need to share information promptly and to the maximum extent permitted under the relevant gateways and under any arrangements set out in any MoUs. This needs to respect any confidentiality provisions, but to be effective colleges need to be approached in a spirit which emphasizes a willingness to share information to the maximum extent possible – not one which sees confidentiality as an insuperable barrier. Different supervisory approaches or accounting standards need to be understood but need not be a significant barrier to exchanges of views and information. A list of ‘standard’ agenda items for a college is included in the Annex.

There is an established body of international standards on how supervisory colleges should operate to greatest effect. The Joint Forum has set out a number of principles for the operation of colleges [13]. A number of practical issues frequently arise however, especially in connection with membership and coverage.

Who should be included in colleges?

In principle, organizers of colleges should consider including any host supervisor wherever: a) the operations of a group (subsidiary or branch) are significant in that host country; and/or b) the operations in that country are significant to the risk profile of the group as a whole. In practice however there are a number of problems associated with this.

- Too many participants. The effectiveness of any meeting tends to be inversely correlated with the number of participants and colleges are no exception to this. Where a group has operations in many jurisdictions the inclusion of all host supervisors meeting the above criteria, while desirable, may limit the effectiveness of the college. In such cases home supervisors should give careful consideration to alternative or complementary structures. It might be possible for example to put in place a ‘core’ college consisting of the key supervisors and decision makers and complement this with meetings of a larger group in which the emphasis is more explicitly on information flow from the core group.

- ‘Variable geometry’. The composition of colleges or the complementary structures described above need not be fixed. As the circumstances of a group change – for example because of the changing impact of ‘external’ – macroeconomic, macroprudential or political – risks, the membership of the college may be adjusted to reflect that, either on a temporary or permanent basis.

- Home/host asymmetry. The operations of cross border groups often create what might be termed ‘asymmetries of impact’. An example of this is where a subsidiary is judged to be high impact or even of systemic importance in a host country even though its operations may not be of great significance for the group as a whole. In these circumstances the subsidiary, its operations and its risks will be a major concern for the host supervisor but probably less so for the home supervisor. College chairs need to be sensitive to these issues and ask themselves two questions: a) is it really the case that the subsidiary is of minor significance for the group as a whole? And if so, b) what provision can be made to provide the host supervisor with the information and support needed even if they are not part of the main college or are minor players in it?

How can host supervisors increase their effectiveness?

Host supervisors may sometimes feel that they are being ignored or marginalized in college arrangements. While there are no easy answers, this section offers some advice in dealing with this problem.

- Speak up. Host supervisors from small countries may feel marginalized or even intimidated in the presence of home or larger host authorities. But it they need information or support beyond a routine ‘read out’ from the college they should make this known. Examples could be information about how money laundering controls operate at a group-wide level or how host operations might be affected by the implementation of group-wide recovery plans. Such matters can be raised in advance, with a request that they are placed on the agenda either for the main college or any complementary structure, or at least be the subject of a bilateral discussion. Similarly, hosts should flag any matters arising from their supervision which may have a bearing on the understanding or supervision of the group [14].

- Be realistic and explain why you need something. Host supervisors of small parts of a group will not generally be key participants in college arrangements and need to recognize this. Where they do have legitimate needs for information or support they are more likely to be listened to if the reasons for this are set out in a clear and focused way.

- Consider what can you offer. Any dialogue is likely to be more effective if both parties are able to bring something to the discussion. While the home supervisor will always be the dominant partner, they may not be aware of the high impact of the subsidiary in a host country, of differences in supervisory approach or coverage in the host, or developments which may have wider significance to an assessment of group-wide risks, governance or culture.

|

Illustration: Being heard as a host Securities company X has its head office in country A. It operates in 25 countries globally through subsidiaries, one of which is located in country B. Subsidiary B accounts for only 3% of the group’s global income. However it is one of only two securities firms in country B where securities firms are key to the government’s campaign to increase the amount of private sector saving for retirement. Colleges in the past have consisted largely of Supervisor A reporting on X’s annual performance and providing an outline of its supervisory program for the year ahead. Two other host supervisors from countries in which X has a large presence have then been asked to report on developments there. Supervisor B has taken part by video link. On this occasion supervisor B has a number of issues they would like to raise, namely:

When supervisor A calls an annual college, supervisor B might consider making representations to supervisor A ahead of the meeting in the following way:

|

Business as usual or crisis management?

There is an important distinction in principle between colleges as facilitators of ‘business as usual’ supervision and crisis management. This is a complex area and the following principles need to be borne in mind.

- Recovery planning is concerned with how firms would recover from severe stress to continue as going concerns. This is predominantly a matter for firms’ management but one in which supervisors take a close interest. Supervisory colleges should, accordingly, always discuss recovery planning as part of ‘business as usual’ supervision [15].

- Resolution planning is concerned with the arrangements for dealing with high impact or systemic financial institutions once they have failed or are failing [16].

o Resolution planning requires the creation of a resolution authority with the necessary powers and tools. This authority rather than the supervisor is responsible for resolution planning.

o Resolution authorities for groups which are judged to be systemically systemic (SIBs) should have convened separate crisis management groups (CMGs) to discuss resolution planning [17].

o The general assumption is that non-systemic institutions would not be subject to special resolution arrangements but, in the event of failure, would be dealt with using normal liquidation procedures. In such cases it may be appropriate for either the supervisory college or a group of resolution authorities to consider arrangements for general ‘failure management’.

In light of the above, while it is not possible or desirable to specify exactly how international coordination would work in all cases, it is possible to identify a number of imperatives:

- Supervisory colleges should discuss all ‘business as usual’ matters, including recovery planning.

- CMGs should discuss resolvability and resolution planning for SIBs.

- Where both colleges and CMGs exist for a firm or group there needs to be communication and coordination between these, notwithstanding their separate formal responsibilities.

- Where this demarcation is not clear cut this needs to be addressed. In the meantime, one of the existing coordination structures needs to discuss failure arrangements and it needs to be clear where that responsibility lies. In such cases the substance (that someone is looking at this) is more important than the form (who that is).

|

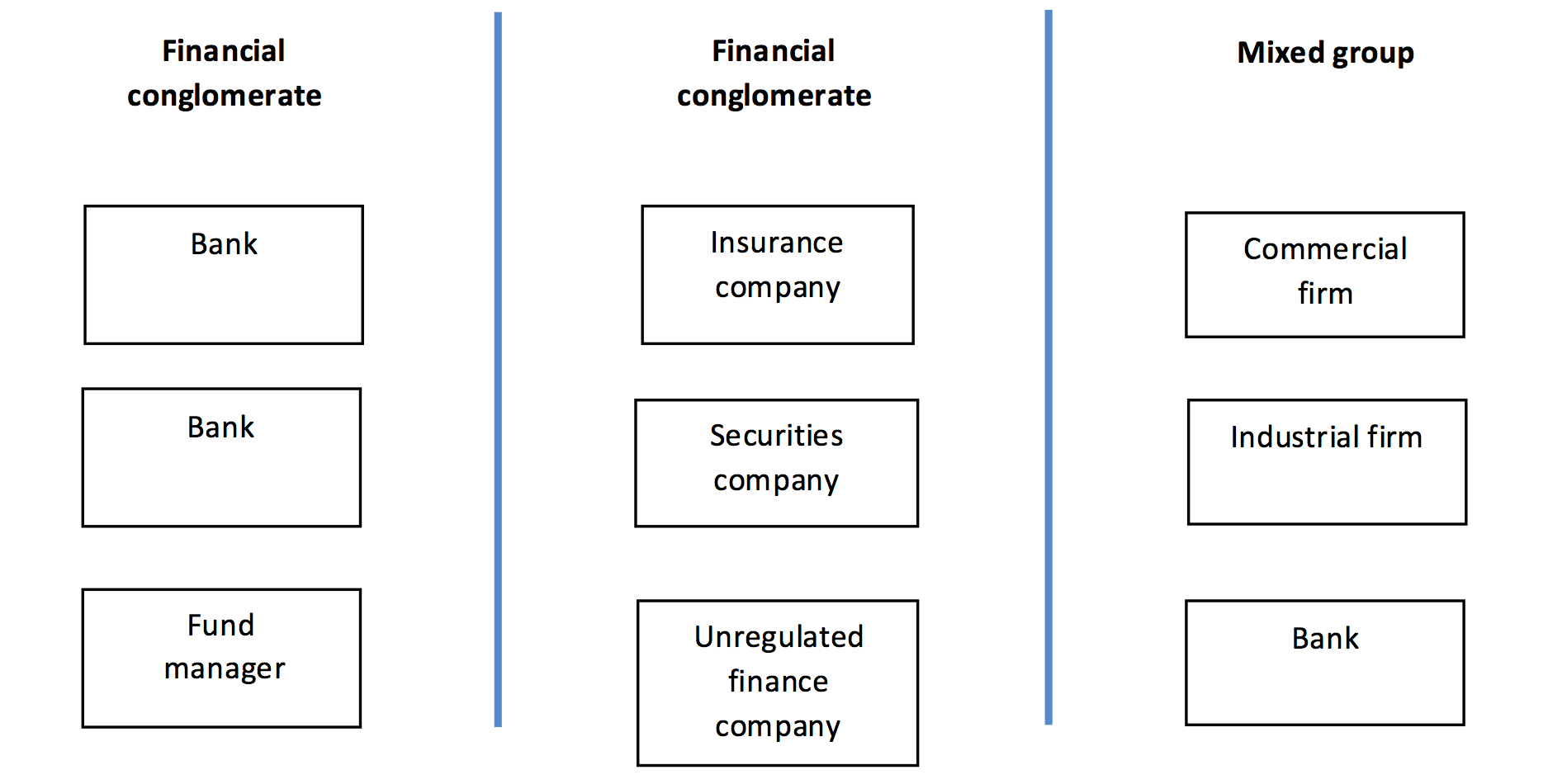

Supervision of cross border and cross sector groups (conglomerates)

The above sections focused principally on supervisory arrangements for firms that have cross border operations in a single sector such as banking, insurance, securities or fund management. Many firms which operate across borders also operate in multiple sectors – potentially (and to the extent permitted by local regulation) including some which are unregulated - making them cross border conglomerates. Most of the issues set out in the earlier sections apply equally to conglomerates and this section focuses specifically on issues arising from firms operating across sectors. The (much simplified) diagram below shows a number of possible structures involving both cross-sector and cross-border businesses.

The form that financial groups take is frequently dictated by regulatory rules in the countries in which they operate. These tend to be particularly restrictive where the conglomerate contains a bank, reflecting concerns that this may be susceptible to various types of contagion from elsewhere in the group. In a number of countries financial conglomerates are either prohibited altogether or allowed only on the basis that there is strict separation or ‘ring fencing’ of the non-bank elements. It is also common for there to be a prohibition on banks owning or being owned by industrial or commercial firms, because such firms are not subject to financial regulation and may be judged to be a source of contamination which may undermine the bank’s financial health.

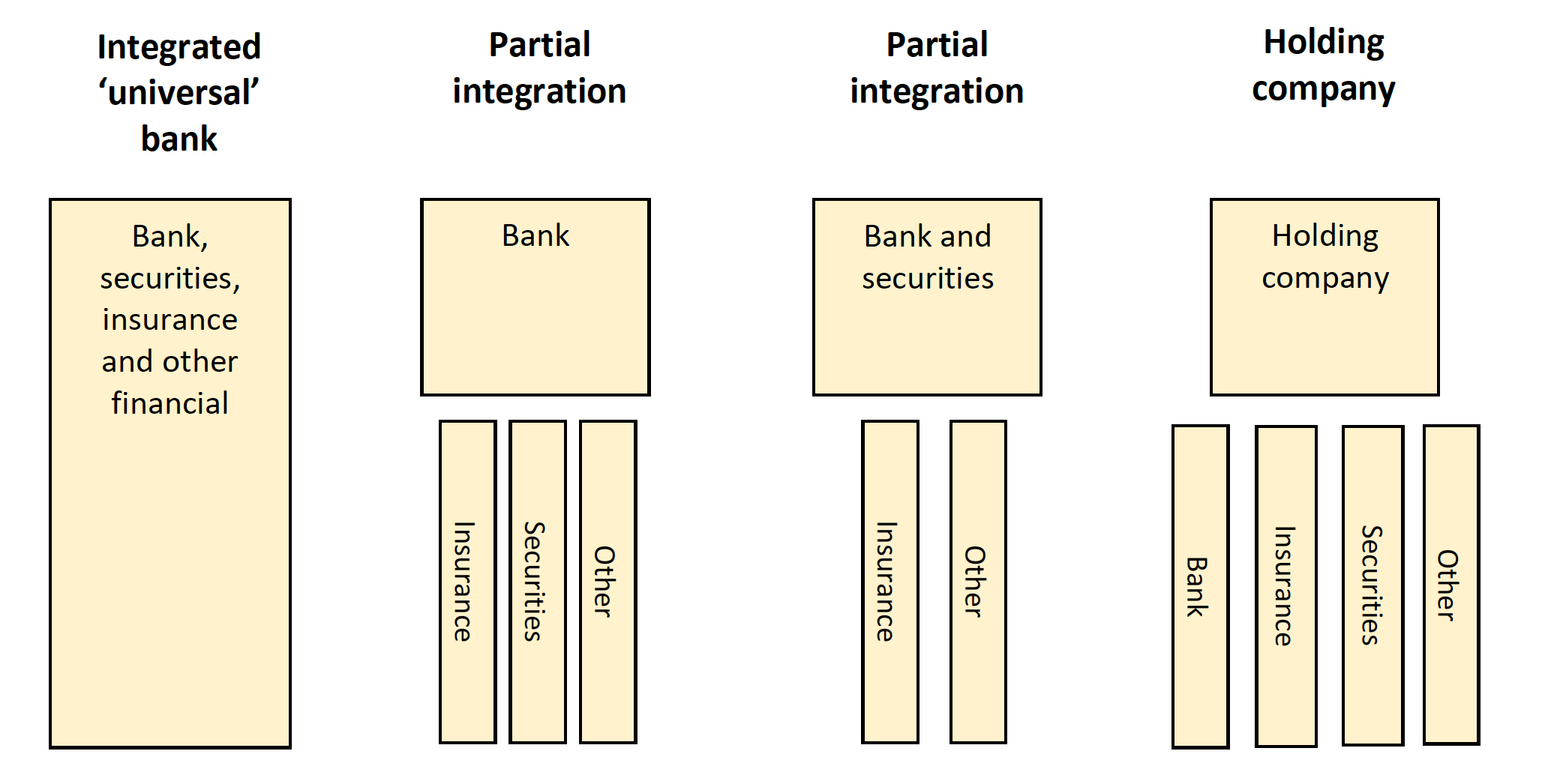

Supervisors focus particularly on bank-led conglomerates because of the particular importance attached to the soundness and stability of banks and the scope for non-banking activities within a group to be a source of risk. The diagram below shows a variety of legal forms that conglomerates may take, with particular focus on bank-led groups.

- The ‘universal’ bank model is one in which banks are permitted and choose to operate across several financial sectors (such as securities, insurance or fund management) within the same legal entity. Such structures are marketed as ‘one stop shops’ able to provide customers with a range of services from under a single roof. Such structures inevitably entail cross sector financial interlinkages within the bank with particular challenges for supervisors. Groups may be structured as universal banks in their home countries and in hosts if permitted by regulation.

- The first ‘partial integration’ model shown is a group headed by a bank with other activities taking place in subsidiaries (which may be domestic or cross border). These may be other regulated financial services (securities or insurance), other financial activities (such as leasing or finance companies), or (where permitted) non-financial activities. The existence of subsidiaries creates a degree of insulation, although for the reasons given above this does not provide full insulation to the bank.

- The second ‘partial integration’ model shown is one headed by a single legal entity engaged in cross-sector and cross-border business but with subsidiaries involved in other financial (and possibly non-financial) activities. This may include, for example, leasing or finance companies which while financial in nature, may not come under the oversight of banking supervision, or (where permitted) non-financial companies.

- The final structure shown is headed by a holding company and as such is not a bank-led group but is shown for purposes of illustration. Holding companies are common corporate structures and not confined to financial groups. A holding company is set up specifically to own the shares of subsidiary companies. The supervisory approach to holding companies varies. In some countries they are not supervised because they do not actively engage in regulated activities. In others they are subject to authorisation and supervision because of the influence they have de facto on the financial group. And in some they are not allowed at all because of their ambiguous status and the difficulty in supervising them.

Risks from conglomerates

Supervision of firms operating across sectors as well as across national borders poses all of the challenges outlined in the sections above together with additional ones arising from the cross sectoral nature of the business. Conglomerate structures may be a source of strength if businesses are appropriately diversified and have solid financial footings. Or they can be a source of weakness to the constituent entities if risks are linked or correlated, or if the level of capital in the group is insufficient to support the solo and group level risks being run [18].

The following deals mainly with challenges arising in the supervision of cross border conglomerates. Many of the issues apply equally to conglomerates operating in a single jurisdiction – for example where entities in the conglomerate are supervised by two or more sectoral supervisors between whom communication or coordination may be imperfect.

- There is a need to understand all of the businesses undertaken in the different sectors and the risks these pose to the group and its constituent parts. This is an illustration of ‘transparency risk’ which is not unique to cross border conglomerates but may be particularly acute in such cases.

- There must be clarity regarding the structure, functions and location of management and controls. While each legal entity within a conglomerate will have its own control and management structures there also needs to be a level of group-wide oversight to ensure that intra-group and external risks are identified and managed. The risks in a conglomerate are not the same as the sum of those in its constituent entities. Overall risk should in principle be lower but may in some cases be higher.

- There is a paramount need to avoid double gearing – in effect the application of the same capital to several different legal entities. It is essential that the capital available to each legal entity is distinct and unencumbered. Supervisors may have difficulty in identifying double gearing where structures and accounting practices are complex or opaque. The issue is not unique either to cross border or cross sector activities but it may be harder to identify in complex international structures spanning multiple sectors.

- It may also be difficult fully to identify intra group exposures. These should ideally take place at arm’s length and any potential commitments or liabilities from one part of the group to another should be wholly transparent. And there is the separate issue of different entities within a group having common exposures to the same counterparty, giving risk to group-wide concentration risks which are not apparent at the levels of individual entities.

- The nature and standard of supervision may vary markedly across the parts of the group. Whilst there has been a growing level of coordination of supervision in banking and insurance in recent decades, standards, approaches and coverage still vary widely in other sectors. This may give risk to arbitrage risk where standards are different or dark corners where firms are able to exploit gaps in regulation or supervision in host countries to undertake business that may be effectively unregulated.

The Joint Forum has set out a number of principles for the supervision of conglomerates [19]. Many of these are similar to those which would apply to any financial group. Supervisors need clear legal powers and structures must be supervisable. Opaque structures in which it is not possible at the outset to discern the business activities undertaken, financial and other inter-relationships, the risks resulting from these, capital adequacy and the effectiveness and location of management should not be authorized in the first place. Supervisors need to remain alert to the possibility that groups may start out with supervisable structures but evolve in a way which makes them increasingly opaque or unmanageable.

In addition, there are a number of principles that apply specifically to cross border conglomerates.

- College arrangements should be put in place involving relevant host supervisors. Unlike purely single sector colleges these need to be cross sectoral in nature. A lead supervisor should be appointed tasked with operating the college in the most effective and efficient way. The lead will usually be taken by the home consolidated supervisor and where there are several functional supervisors in the home jurisdiction this will often (though not always) be the lead banking supervisor. The most efficient and effective arrangement needs to be considered case-by-case on its merits.

- Supervisors should have access to any unregulated entities which should be transparent about the activities they are undertaking, the risks inherent in these and how these are controlled. If a host supervisor is unable or unwilling to secure the necessary information or cooperation regarding unauthorised entities, the home or lead supervisor should take this up with the management of the conglomerate as a matter of priority.

- There may be a particular challenge where the ‘top’ or holding company is itself unregulated so that supervisors have no direct powers over it. In such cases supervisors should seek the necessary information from the management of the regulated entities that are subject to its jurisdiction. This could be the most ‘senior’ regulated entity or even a subsidiary. If the holding company and/or its regulated affiliates are resistant to reasonable contact and information sharing with the supervisor this raises important concerns about the group’s supervisability and potentially its risk profile. This in turn may influence the supervisory stance towards the regulated entities. It should be made clear to the management of the group that seeking to limit contact and information flows to those parts of the group which are subject to formal regulation is unacceptable.

- The college needs to satisfy itself that capital is sufficient at both group and solo levels and in both normal and stressed conditions. This assessment must take account of any direct or indirect capital requirements associated with unregulated entities. The group must be able to demonstrate that it has an effective capital planning process which takes full account of all sources of risk, including from unregulated entities.

- One of the core functions of the college – mirroring that of solo functional supervisors – is to satisfy itself that there is a coherent and effective management structure within the conglomerate capable of identifying and managing risk. Supervising a conglomerate can be a daunting task but supervisors working in concert to hold management to the necessary standards can make this more manageable.

- A key part of this is to seek assurance that group management includes a comprehensive risk management function which identifies, monitors and manages the diversity of risks associated with a conglomerate structure. This entails not merely technical risk management but a demonstrably effective risk management culture set from the top of the group.

|

Issues in the supervision of conglomerates in practice

The logic governing the establishment of colleges for cross border conglomerates is clear. In practice however it is often difficult either to establish the necessary cooperative arrangements or to make them effective. Some of the reasons for this can be illustrated with reference to the following illustration. While the example may seem rather complex it is in fact highly simplified. It is intended to demonstrate a number of generic practical issues involved in the consolidated supervision of conglomerates.

Illustration – cross border collaboration in practice

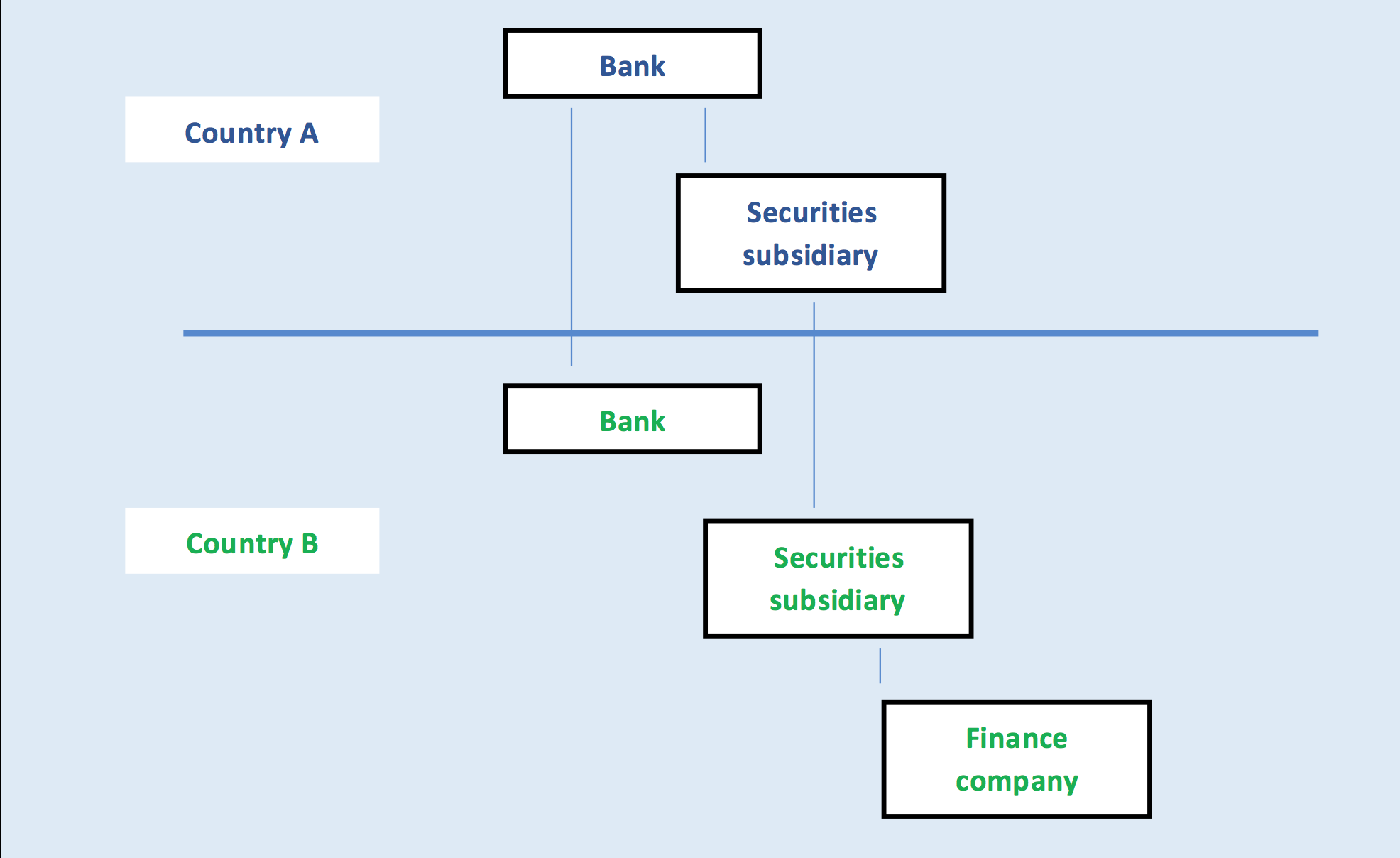

Conglomerate X consists of a bank (Bank A) with a securities subsidiary in country A (‘Securities A’). The bank and the securities subsidiary both have subsidiaries in country B (‘Bank B’ and ‘Securities B’). The securities subsidiary in country B itself has a subsidiary described as a ‘finance company’ which is not subject to supervision in country B. This relatively simple arrangement is illustrated in the chart below.

The supervisory arrangements in countries A and B are as follows:

- Both countries have separate functional regulators for banking and securities

- Country A has a risk-based prudential supervisory regime for banks and operates a risk-based prudential and conduct regime for securities

- Country B has a more limited risk-based regime for banking and a non-risk-based conduct/enforcement regime for securities

- Country A perceives the need to have effective oversight of the group and is considering putting in place a college arrangement with the supervisors in country B

- All the supervisors involved agree that if there is to be such an arrangement, the lead supervisor for the group should logically be the bank supervisor in country A

- Supervisors in country B agree that the ‘finance company’ is undertaking unregulated activity and that it is therefore not subject to supervision

The imperatives for the lead supervisor of the group (bank supervisor A) are as follows:

- To undertake solo and consolidated supervision of Bank A

- In doing this it has a ‘direct’ interest in the activities and risks in Securities A and Bank B

- It also has an interest – in its roles as both consolidated and lead supervisor –in the activities and risks in Securities B and Finance Company B

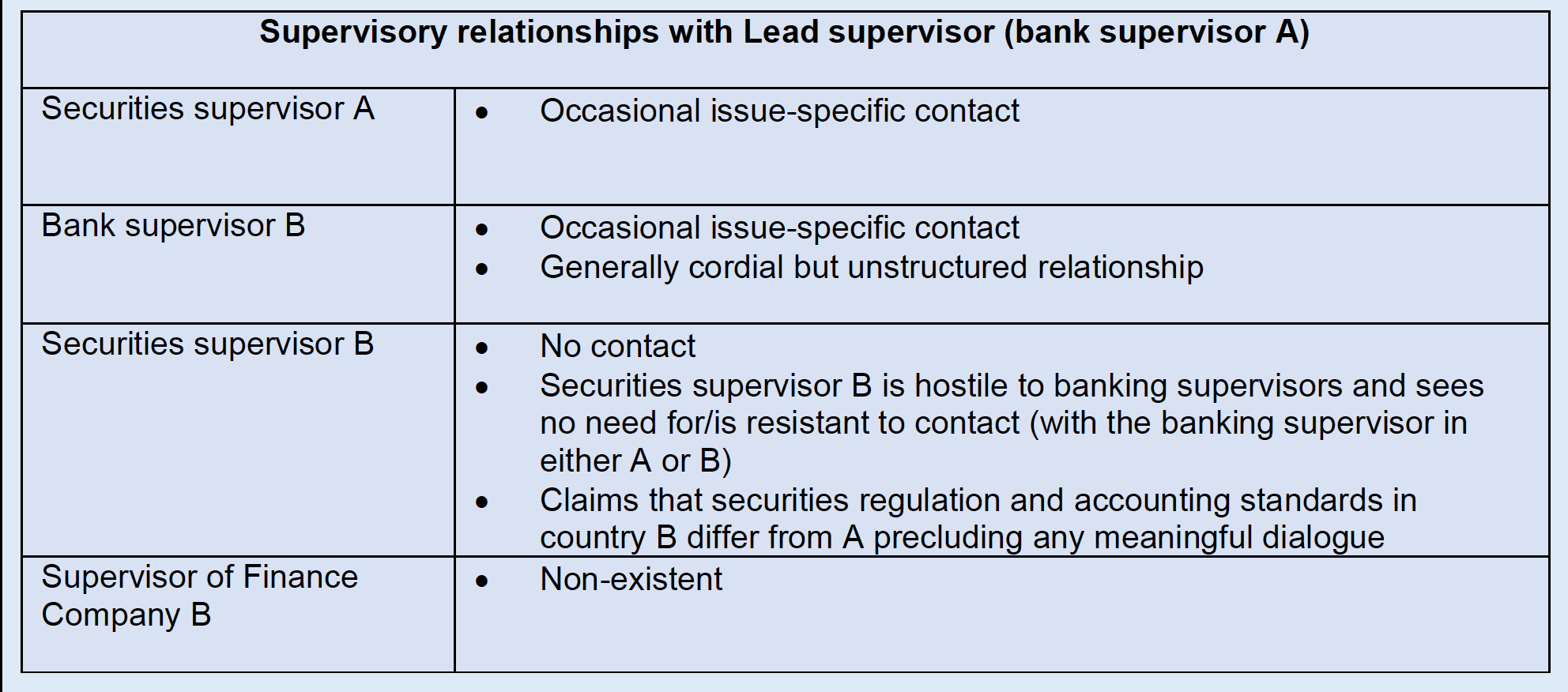

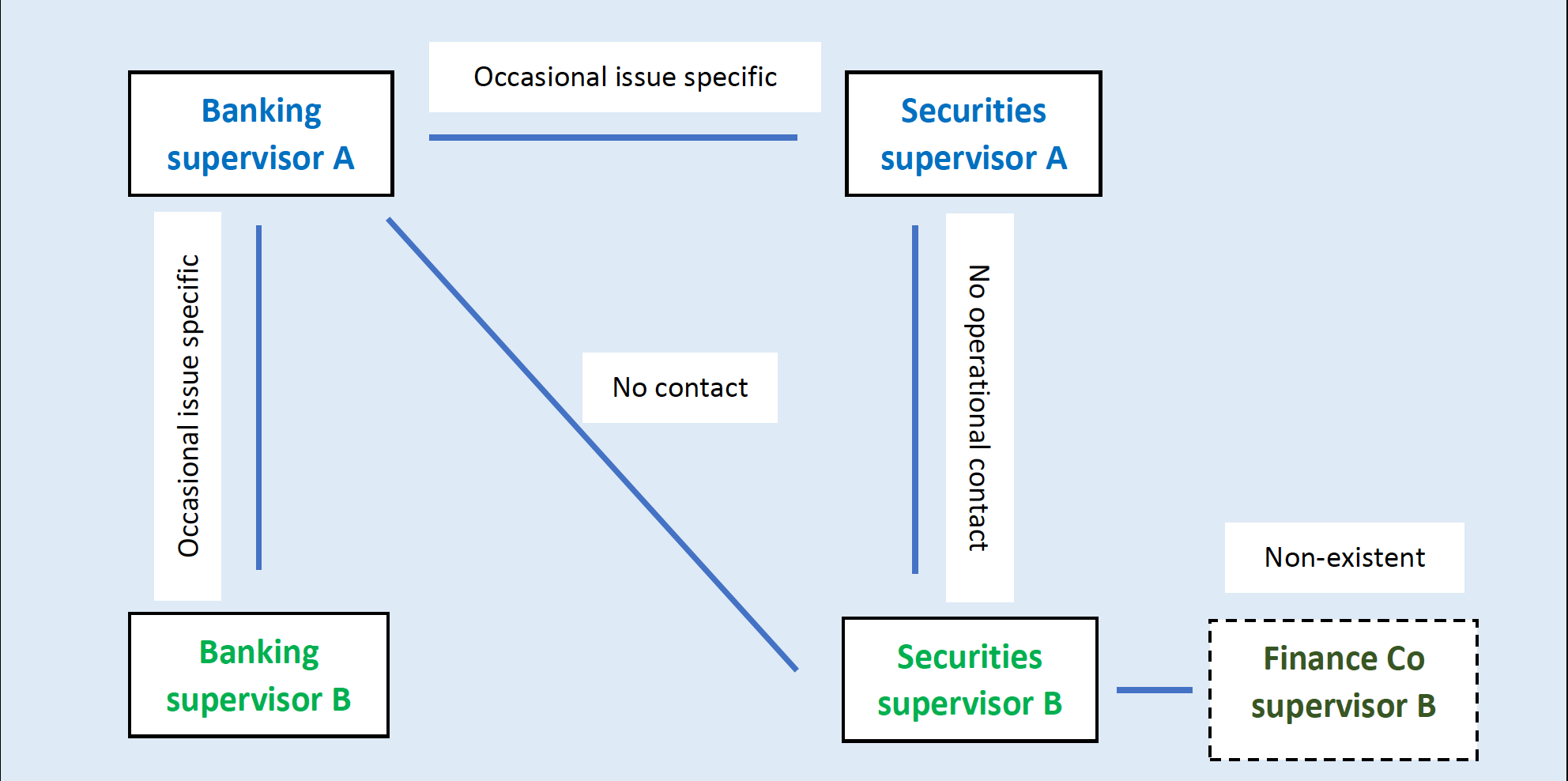

In practice bank supervisor A has limited access to non-bank entities and its oversight of Bank B is shared with host bank supervisor B. For the purposes of illustration it might be supposed that the supervisory relationships involved are as shown in the table and diagram.

There are a number of significant risks in this arrangement which need to be understood and managed, including in particular:

- Failure of Bank B would have severe consequences for Bank A for obvious reasons

- Even though it is theoretically insulated, failure of Securities A would have severe consequences for Bank A as a result of reputational damage and any financial linkages (notwithstanding the fact that client money in both securities firms is segregated, limiting direct losses to their customers)

- Failure of Securities B could have significant implications for Bank A for similar reasons though this impact, and that on Securities A, may be more limited

- Failure of the finance company could have significant group-wide reputational and financial consequences – for example if there are extensive financial linkages. However the extent of these – for example the extent to which financial linkages are at ‘arms-length’ from the group - are hard to discern since it is unregulated.

- From the perspective of bank supervisor B, Bank B would obviously be impacted severely (probably terminally) by the failure of Bank A. Securities B may also be impacted adversely by the failure of Securities A or Bank A – possibly to an extent that securities supervisor B has not considered.

Given the attitudes and supervisory cultures described above, it may be necessary to do the following to work towards a common perspective on group risks.

- Bank supervisor A has the goal of convening a college involving all the bank and securities supervisors in A and B

- There may be initial resistance to this however – particularly from securities supervisor B. Any structured arrangement such as a college will therefore need to be preceded by bilateral contacts in which bank supervisor A explains: a) why an understanding of the risks in Securities B is necessary for effective group-wide supervision and (perhaps) b) why securities supervisor B should not be indifferent to the soundness of other entities in the group

- It may also be necessary to explain to securities supervisor B that the different approaches to supervision – and perhaps accounting conventions – in the two countries and sectors need not preclude a meaningful dialogue about risk

- An early task will be to put in place the necessary information sharing arrangements. This will be necessary for any college but also for any meaningful prior discussions. In discussions bank supervisor A should emphasize the need for a sensible dialogue about risks and avoid stumbling over confidentiality concerns which, while real, can be overcome

- An MoU may be of value in this though here too it will be important not to become mired in quasi-legal issues of drafting or substance

- There needs to be a dialogue with securities supervisor B about sharing whatever information is available about the finance company. Securities supervisor B should be asked to share whatever information it has about the finance company, its operations and its linkages with the rest of the group. They may also be asked to find out more – either directly or through the management of Securities B.

- If these routes fail to uncover what is seen as a necessary level of information, bank supervisor A should take up the matter with the senior management of Bank A, making it clear that the information lacuna is a serious potential source of risk which must be addressed. While the primary purpose of this is to elicit information about the group, the attitude of Bank A’s management will also be a very important indicator of its openness to regulation.

Conclusions

Effective supervision – of any firm regardless of its geographic or sectoral reach – requires a thorough knowledge of its business, the risks it is running and how effectively these are controlled. The challenge of developing this level of understanding is compounded where financial firms operate across borders and even more so when cross border firms operate in multiple sectors.

This Note has set out the main challenges and suggested a number of steps towards overcoming these. The main message is that effective communication and collaboration among supervisors – both internationally and across sectors – is fundamental.

While there is extensive literature on what formal structures – for example colleges – should look like, this Note has drawn on practical experience to suggest how these might be made to work better in practice. While there obviously needs to be a degree of formality in the structuring of college arrangements and information exchange, coordination arrangements work best on the basis of flexibility, trust and a shared understanding of the value of coordination and collaboration.

Annex: Supervisory College Agenda Items

- Examples of agenda items for colleges (illustrative and non-exhaustive. Note that the depth of oversight should will be greater in the case of firms judged to be systemically important)

- Stock-take of group structure, significant entities and engagement of significant (host and sectoral) supervisors

- Assessment/reporting on any changes to strategy or business model

- Key financial reports and firm-generated financial information

- Stocktake of material financial interlinkages and commitments

- Supervisory assessments and findings – group level and involving all significant entities (cross border and cross sector)

- External (macroeconomic and macroprudential) factors impacting the group and significant constituent entities

- Assessment of management and controls – structures and effectiveness – at group level and in significant constituent entities

- Assessment of governance (board and senior management) especially management of risk and culture

- Results of material third party reviews (external audit, external actuarial, consultants)

- Assessments of financial soundness (capital, earnings, liquidity)

- Results of internal capital and liquidity management plans (ICAAP, ORSA, ILAAP etc)

- Results of stress/scenario testing – both internal and supervisory requirements

- Recovery plans

- Assessment of AML/anti financial crime reviews

- Results of model reviews

- Progress under former/existing supervisory plans – issues arising

- Supervisory plans – group level and significant constituent entities

- For SIBs – the status of resolution planning

o Crisis preparedness plans (from CMG where this exists)

o Agreement on nature/responsibility for failure/resolution planning (if CMG does not exist and/or this is not clear)

References

Toronto Centre. Group Wide Consolidated Supervision in Bank and Financial Groups February 2016

Toronto Centre. Risk Based Supervision March 2018

Toronto Centre. The Development and Use of Risk Based Assessment Frameworks January 2019

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Principles for Effective Supervisory Colleges June 2014

Joint Forum. Principles for the Supervision of Financial Conglomerates September 2012

Joint Forum. Report of Supervisory Colleges for Financial Conglomerates September 2014

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Final Guidelines on the Identification and Management of Step-In Risk October 2017

Toronto Centre. Exit Policy: Taking Supervisory Action To Deal With Non-viable Financial Institutions October 2020

Toronto Centre. Recovery Planning August 2020 (a)

Toronto Centre. Resolution: Implications for Supervisors August 2020 (b)

Financial Stability Institute. Cross Border Resolution Cooperation and Information Sharing January 2020

Footnotes

[1] This Note was prepared by Paul Wright.

[2] See for example Toronto Centre March 2018 and January 2019.

[3] See for example Joint Forum September 2012 and Toronto Centre February 2016.

[4] Throughout this Note the term ‘home’ supervisor refers to the authority in the principal country of domicile of the firm. In the case of a firm with branches, that is the country in which the head office is located. In the case of subsidiaries, it is the country where the parent is located. The home supervisor will be responsible for undertaking consolidated supervision of the firm or group. The ‘host’ supervisor is the supervisory body in the jurisdiction where the branch or subsidiary is located.

[5] The group will also have its own consolidated balance sheet and will usually have to meet capital and other requirements at a group consolidated level in addition to "solo" requirements imposed on individual entities. It is also worth noting here that the independence of subsidiaries’ boards may be compromised by the deployment of senior staff from the parent institution to the board of the subsidiary.

[6] And even, in some recorded cases, when parent supervisors have had prior assurances from parents that this would not happen.

[7] See Basel Committee October 2017.

[8] Though there will be risk implications for the customers who end up doing business with the firm. Similar issues will arise where sales staff are sent to a third ‘host’ country to encourage business. In some such cases there may be no representative office. Some supervisors insist, usually on competitiveness or level playing field grounds, that representative offices operate for only a limited time and must be closed or turned into branches once that has lapsed.

[9] This raises issues of the scope of regulated activities and regulatory powers and the extent to which these are aligned with supervisory objectives which are beyond the scope of this Note.

[10] See Toronto Centre February 2016.

[11] There are three key parties (in addition to local management) who need fully to understand the business – and the risks – being undertaken by a subsidiary. These are: a) the group parent; b) the host supervisor; and c) the home supervisor. The most pernicious form of dark corner is where none of these is fully aware of the activity or its potential risk implications. Where the activity is not regulated in the host country it is likely (though not inevitable) that the group parent may be aware of what is going on but the supervisors are not. This poses unacceptable risks.

[12] The existence of an MoU does not create a legal obligation on a supervisor to share information. To take an extreme example a supervisor could not take legal action against another with which it has an MoU because they failed to do so. MoUs create an expectation that information will be shared on a ‘best efforts’ basis and it is important that the drafting reflects this.

[13] See Joint Forum September 2014.

[14] In some extreme cases host supervisors have been known to impose restrictions on local entities where they had serious concerns which home supervisors persistently failed to address. This is a retrograde step which is generally to be discouraged. It should be used as a last resort only where there are serious risk issues which home/host collaboration has failed to resolve.

[15] See Toronto Centre August 2020 (a).

[16] See Toronto Centre August 2020 (b). The Financial Stability Board has indicated that resolution strategies should apply to all systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) – this by definition includes systemically important non-banks. In practice however most countries (especially in emerging markets) have only begun to develop and apply FSB style resolution powers, tools and procedures to systemically important banks (SIBs). This is either because their non-banks are not of systemic importance, or because they have seen SIBs as the priority and not yet moved on to other sectors. For this reason, what follows here refers to SIBs (ie banks) only.

[17] Though responsibilities may be complex where the ‘asymmetry’ problem exists – where for example a branch or subsidiary may be judged systemic in the host country while the parent is not judged to be systemic in the home country.

[18] These points are elaborated in Toronto Centre February 2016.

[19] This section draws on the Joint Forum Principles for Supervision of Financial Conglomerates September 2012.