A Survey of Financial Supervisors And Financial Services Providers in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia

Foreword by Funders

Tackling financial exclusion and helping organizations, financial service providers and governments to promote affordable and appropriate financial products and services remains one of the highest priorities for Comic Relief and Jersey Overseas Aid. In 2017, both organizations joined forces to address financial exclusion in Sierra Leone, Rwanda, and Zambia through a joint funding programme called Branching Out: Financial Inclusion at the Margins. This Åí8 million partnership has to date helped hundreds of thousands of marginalized farmers, entrepreneurs and communities to save, to create stronger businesses and to plan for the future in the face of any emerging stressors and crises.

The advent of the coronavirus pandemic has had a deep impact on lives throughout our three operating countries. It has created a range of challenges which could result in greater financial exclusion for some of the most vulnerable people in society. However, it has also emphasized the importance of saving and financial inclusion for personal and business resilience. It has contributed to the development of innovative approaches to financial services, the increased adoption of digital finance, and successful behaviours and policy shifts that supervisory bodies have taken to dampen the effects of not only the pandemic but other future crises, thus promoting systemic resilience.

The present research takes advantage of the natural experiment conditions the pandemic has provided to determine guidelines for resilient financial inclusion. Comic Relief and Jersey Overseas Aid are extremely excited about the work that Toronto Centre has done, and to promote and share these findings and recommendations in the hope that they will be reviewed, built upon and adopted by organizations, financial service providers and supervisory bodies around the world.

The report draws on the lessons that main actors in Zambia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone have learned about resilience in the times of COVID-19. It identifies key insights into how these actors have continued to expand financial inclusion and what the current risks are:

- The growing importance of digital financial services both in the short-term and long run as services expand;

- The importance of an environment that is conducive to digital inclusion for the most marginalized markets;

- The rising risks relating to trust and concerns around data privacy, transparency and fraud in a time when face-to-face models are more difficult to achieve;

- The need to enhance information gathering for effective and realistic supervision.

Though the coronavirus pandemic has presented unique challenges for financial inclusion around the globe, it is clear that it has also brought about exciting opportunities and new ways of thinking. We remain committed to financial inclusion and welcome this research as a central source for resilience throughout the sector.

Jos. Morell-Ducós

Portfolio Manager: Financial Inclusion

Branching Out: Financial Inclusion at the Margins

Comic Relief and Jersey Overseas Aid

Executive Summary

OBJECTIVES

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about significant disruptions beyond public health. This research project examines the impact of the pandemic in Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Zambia from a financial inclusions lens by examining through examining the pandemic’s impact on the delivery of financial services.

The study explored how COVID-19 affected the face-to-face (F2F) delivery of financial services to financially excluded groups such as women, youths, small and medium enterprises, smallholder farmers and rural households. Given that these excluded groups had limited financial access even before the pandemic, the study sought to explore how the changes in delivery mechanisms due to COVID-19 impacted the financial inclusion of these groups. The study further identified the implications of the changes in delivery channels to supervisory risks to which financial supervisory authorities should be alerted.

The study aimed to recommend practical steps that financial supervisors and other authorities in these countries can take to build resilience in financial services delivery and financial inclusion. The research involved financial supervisors, financial services providers (FSPs), and consumer associations drawn from Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia, representing East, West, and Southern Africa, respectively. The research methodology involved an initial online survey complemented with webinars (one with FSPs and another with financial supervisors), and interviews with several respondents to explore in-depth the pertinent issues emerging from the survey.

MAIN FINDINGS

In response to COVID-19 health protocols, F2F financial services delivery through physical branch networks was significantly reduced across all three countries as FSPs implemented measures meant to reduce in-person contact and/or the handling of cash. FSPs in the three countries adapted their financial services delivery channels differently in response to COVID-19. FSPs in Rwanda focused on non-F2F mobile and internet banking; FSPs in Zambia placed more emphasis on the use of agents and mobile banking; and FSPs in Sierra Leone mostly retained delivery via F2F channels – possibly due to the comparatively less severe spread of COVID-19 in the country – but maintained strict COVID-19 health protocols.

The major adaptation during COVID-19 of shifting from F2F service delivery to non-F2F delivery, notably to digital, was not caused solely by COVID-19. FSPs were already moving to non-F2F digital delivery pre-COVID for business reasons. However, the challenges created by COVID-19 had a catalytic effect on accelerating the FSPs’ shift to digital delivery of financial services. In all three countries, FSPs came to realize that digitalization was inevitable and fast-tracked plans for digital delivery.

Digital adoption rates in the target countries pre-COVID, and government policies already in place to promote digital delivery, played a pivotal role in the ease with which FSPs transitioned from F2F to non-F2F delivery during COVID-19. For example, the Rwandan government, in their efforts to promote a “cashless” society, worked with mobile network operators to offer a “90-day zero charge” on mobile transactions to encourage the shift to the use of mobile payments. In Zambia, the supervisory authorities removed the limit on agents’ transactions to encourage the use by FSPs of agents.

So far, FSPs have not yet capitalized on the potential to expand outreach to financially excluded groups – at least not in the near term. Although the move to non-F2F channels offered the possibility of reaching out to financially excluded customer segments, and also lowering the costs of delivery and making it easier for the FSPs to take on potentially less profitable customers from excluded groups, in practice this potential remains latent due to several barriers. Firstly, the financially excluded, especially women and those in rural areas, have limited access to the technology needed for digital access.

Secondly, the level of digital literacy, deemed low before the pandemic in all three countries, continued to be a barrier for some groups, especially women and rural populations. Thirdly, issues of trust and concerns around data privacy and transparency continued to be hindrances to quick adoption of digital delivery channels.

The shift to non-F2F service delivery and innovations may heighten risks in the financial system, such as money laundering where know-your-customer procedures are compromised, risks of abuse in market conduct and consumer protection, and cyber security risks. Financial supervisors would have to closely monitor and manage the emerging risks from a financial stability perspective while keeping their financial inclusion mandate in mind.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our study, based on these three countries, has shown that the underlying stage of digitalization in the country and the type of measures taken by the country in response to COVID-19 had the most impact on whether resilience and financial inclusion in financial services delivery is maintained in the ongoing COVID-19 environment. Going forward, while keeping a close eye on the risks, financial supervisors with financial inclusion mandates can support the potential offered by the shift to non-F2F delivery by FSPs to reach out to financially excluded groups. Support from financial supervisors for national digital financial literacy efforts can yield financial inclusion dividends in the long term as FSPs shift towards digital delivery. In service of their financial stability and financial inclusion mandates supervisory authorities should consider:

Supporting the potential shift to increased digitalization to ensure it enhances financial inclusion through efforts such as working with other stakeholders in government and in the private sector to promote financial and digital literacy, and strengthening consumer protection frameworks to engender consumer trust in digital delivery of financial services.

Increasing communication and sharing the supervisor’s risk assessment of emerging risks (money laundering and financing of terrorism or ML/FT, operational, cybersecurity, etc.) during COVID-19 with FSPs.

Clearly setting supervisory expectations to FSPs through rules or best practice guidelines on the enhanced risk management measures that FSPs should take to ramp up non-F2F delivery of financial services during COVID-19.

Enhancing information gathering for effective supervision of these delivery channels. Given that it may be difficult to conduct onsite inspections during the pandemic, financial supervisors may have to invest more in digital data collection, analysis and use so as to monitor FSPs’ shift to non-F2F service delivery.

1. Overview of the Study

1.1 OBJECTIVES AND CONTEXT1

Toronto Centre (TC) conducted this study into drivers of the disruption brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic in financial inclusion activities in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia. The research project considers the nature of the disruption and the extent of the impact, and identifies possible practical steps that financial supervisors and other authorities in these countries can take to build resilience in financial inclusion activities. This research sought to address the following questions:

i. How has COVID-19 affected the face-to-face (F2F) delivery of financial services to vulnerable groups (such as women, youths, small and medium enterprises, smallholder farmers, and rural households) with limited financial access even before the pandemic, and how has the financial inclusion of these groups been impacted?

ii. What supervisory risks are posed by financial service providers’ changes to delivery models to vulnerable groups due to COVID-19?

The study recognizes that there are numerous studies that have focused on COVID-19 and financial inclusion. It does not seek to replicate the work that has already been done but rather to complement those studies. Two key elements make this study unique:

i. The study focused on the impact of COVID-19 on the ‘last mile’ delivery of financial services – how were FSPs’ delivery mechanisms affected? If FSPs changed their delivery channels or processes to adapt to COVID-19 challenges, how did that affect financial access by the vulnerable groups?

ii. The study acknowledges that due to the changes in i) above, supervisory risks were likely to change or shift, necessitating a response by the financial supervisory authorities.

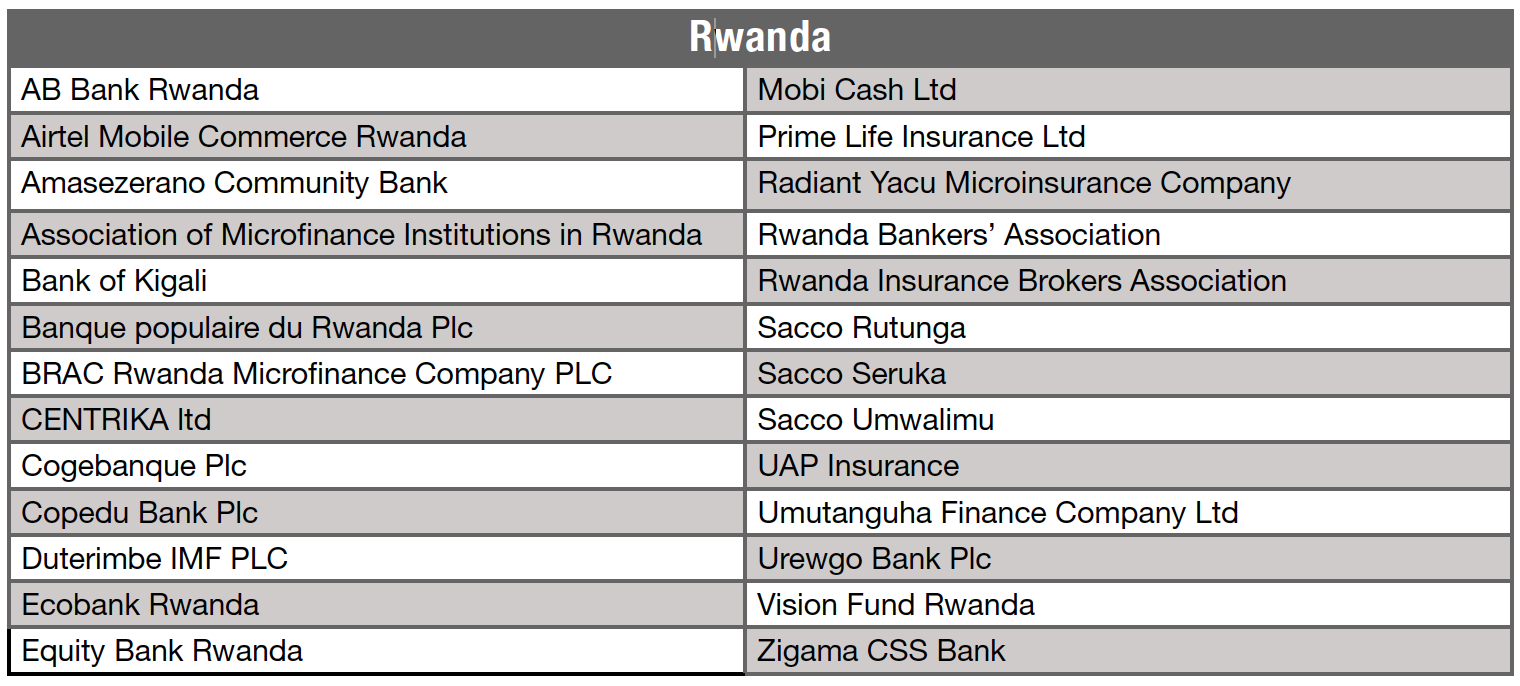

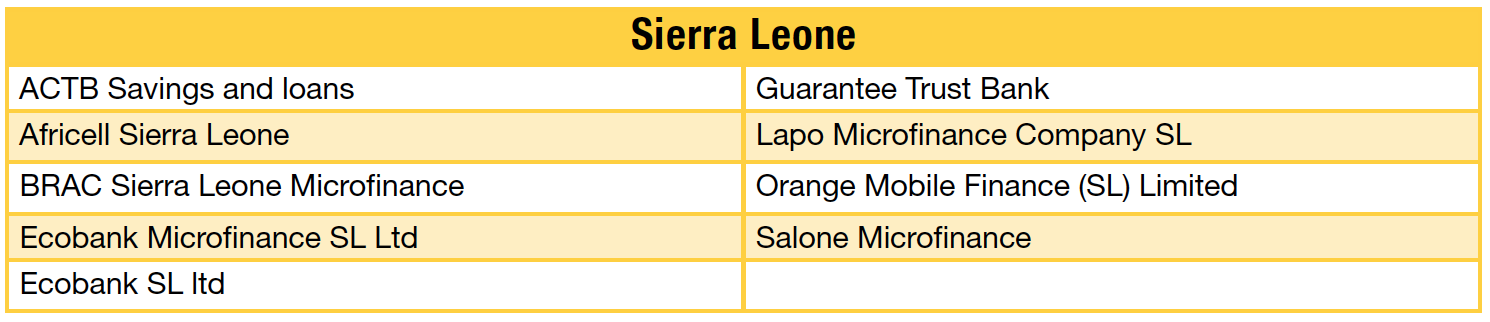

1.2 PARTICIPANTS IN THE STUDY

Key research instruments in this study were a survey of financial supervisors, FSPs and consumer associations in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia, and discussions with them for in-depth understanding of the survey responses. TC appreciated the co-operation and time given by many financial supervisors in the different countries; the National Bank of Rwanda, Bank of Sierra Leone, Sierra Leone Insurance Commission, Bank of Zambia, Pensions and Insurance Authority of Zambia, and Securities and Exchange Commission of Zambia. TC gratefully acknowledges their participation and that of the FSPs and consumer associations listed in Annex 1. The survey instruments are in Annex 2.

1.3 FUNDING

The publication was made possible by grant funding from the Comic Relief and Jersey Overseas Aid partnership called “Branching Out: Financial Inclusion at the Margins”. The aim of this project is to improve access to affordable financial services for those on the margins of society in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia.

1.4 ABOUT TORONTO CENTRE

Toronto Centre’s objective is to promote financial stability and access globally by providing high-quality, practical capacity building programs for financial sector regulators and supervisors, particularly in emerging markets and low-income countries. Stable economies produce an environment for economic growth and job creation, while increased accessibility to financial services is an effective means to break the cycle of poverty. Since it was established as a non-profit organization in 1998, TC has trained more than 15,000 officials from the banking, insurance, pensions, and securities supervision sectors in 190 jurisdictions worldwide.

2. Survey Methodology, Respondent Profile and Pre-COVID Baseline

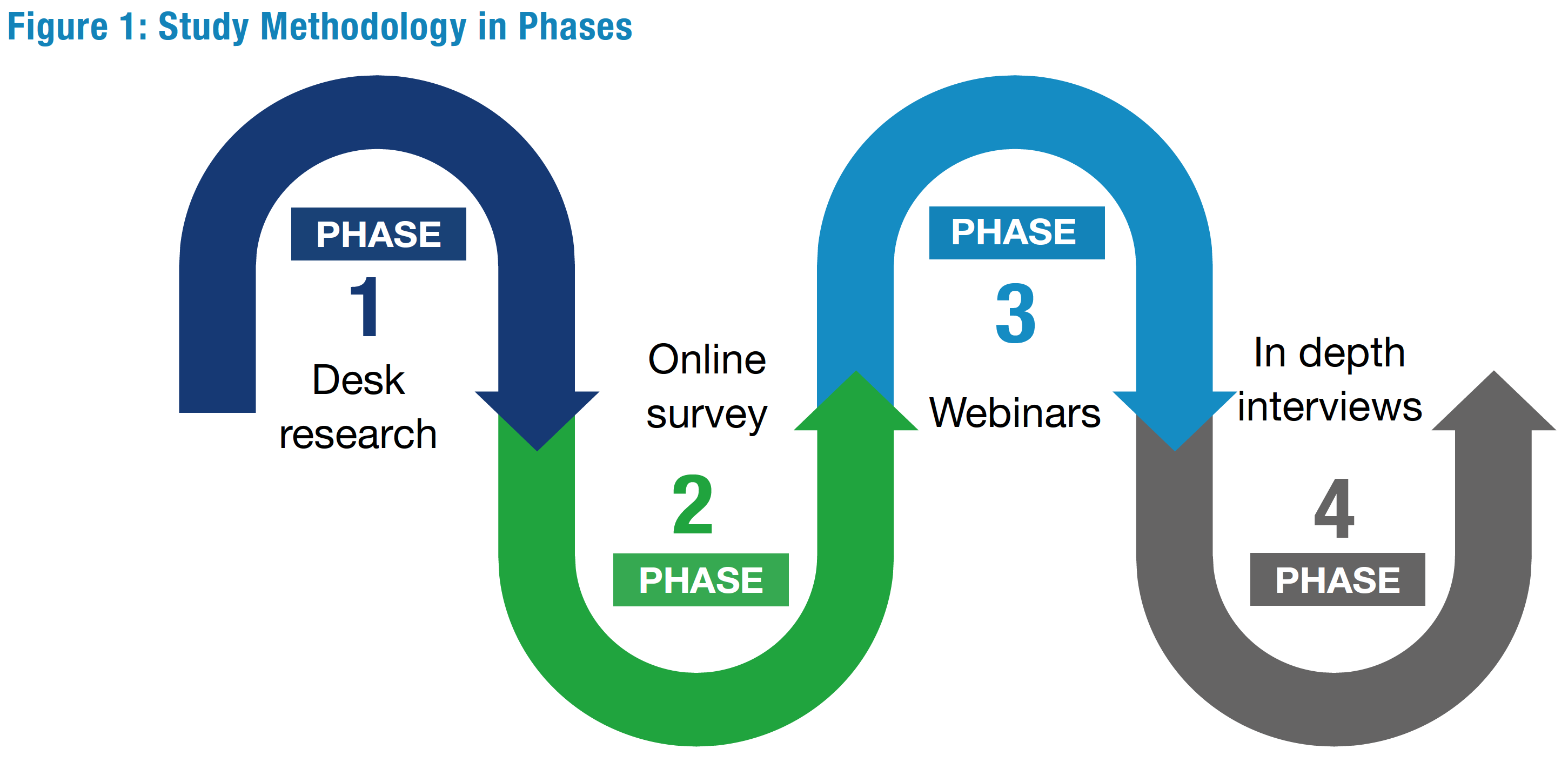

This was a multi-pronged study that entailed engaging with key financial inclusion stakeholders (FSPs, financial supervisors, and consumer associations) in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia. While the four phases shown in Figure 1 below reflect a linear process, the research process was iterative with the study team engaging in dialogue with the stakeholders and mutual learning throughout the four-stage process.

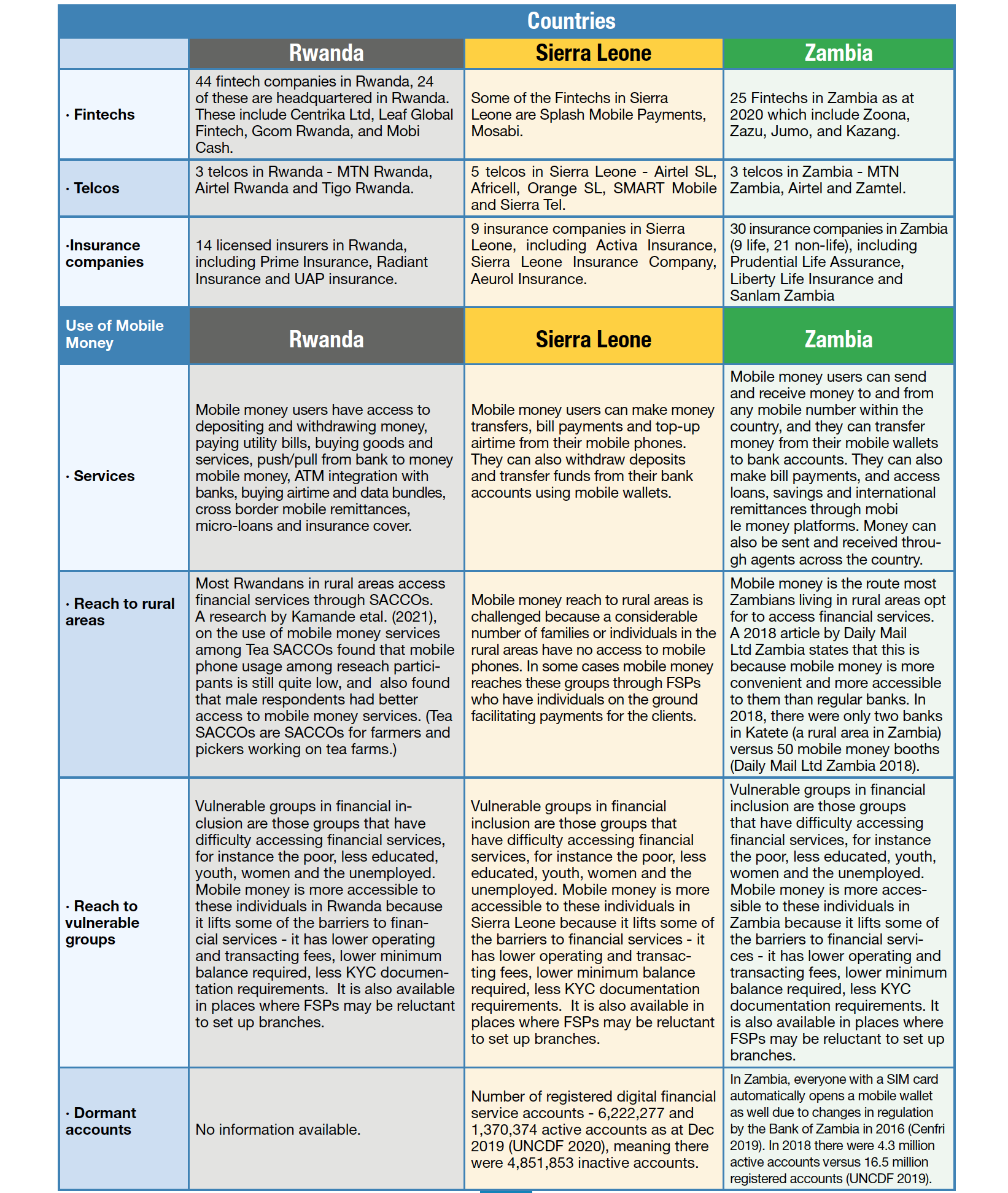

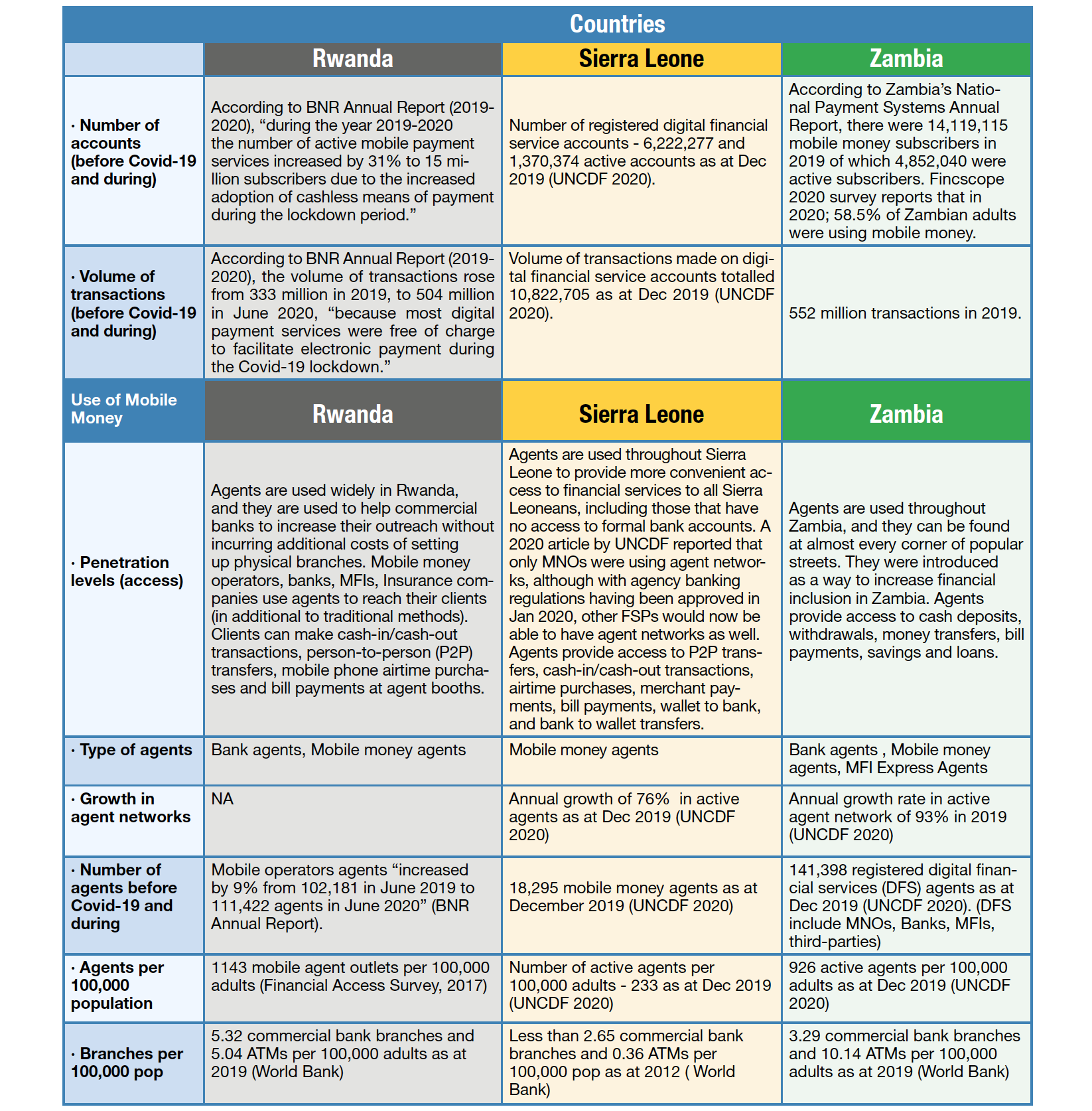

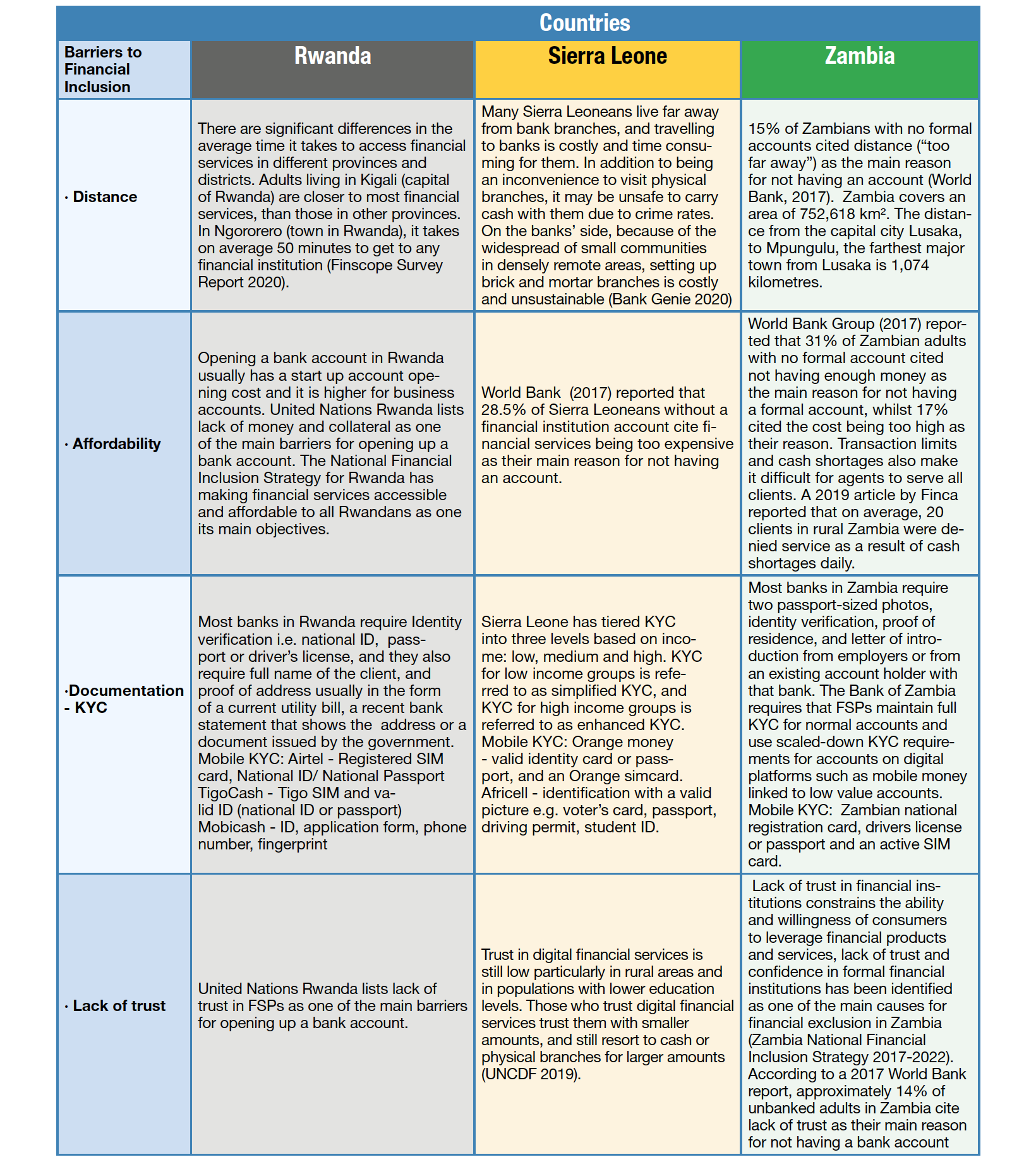

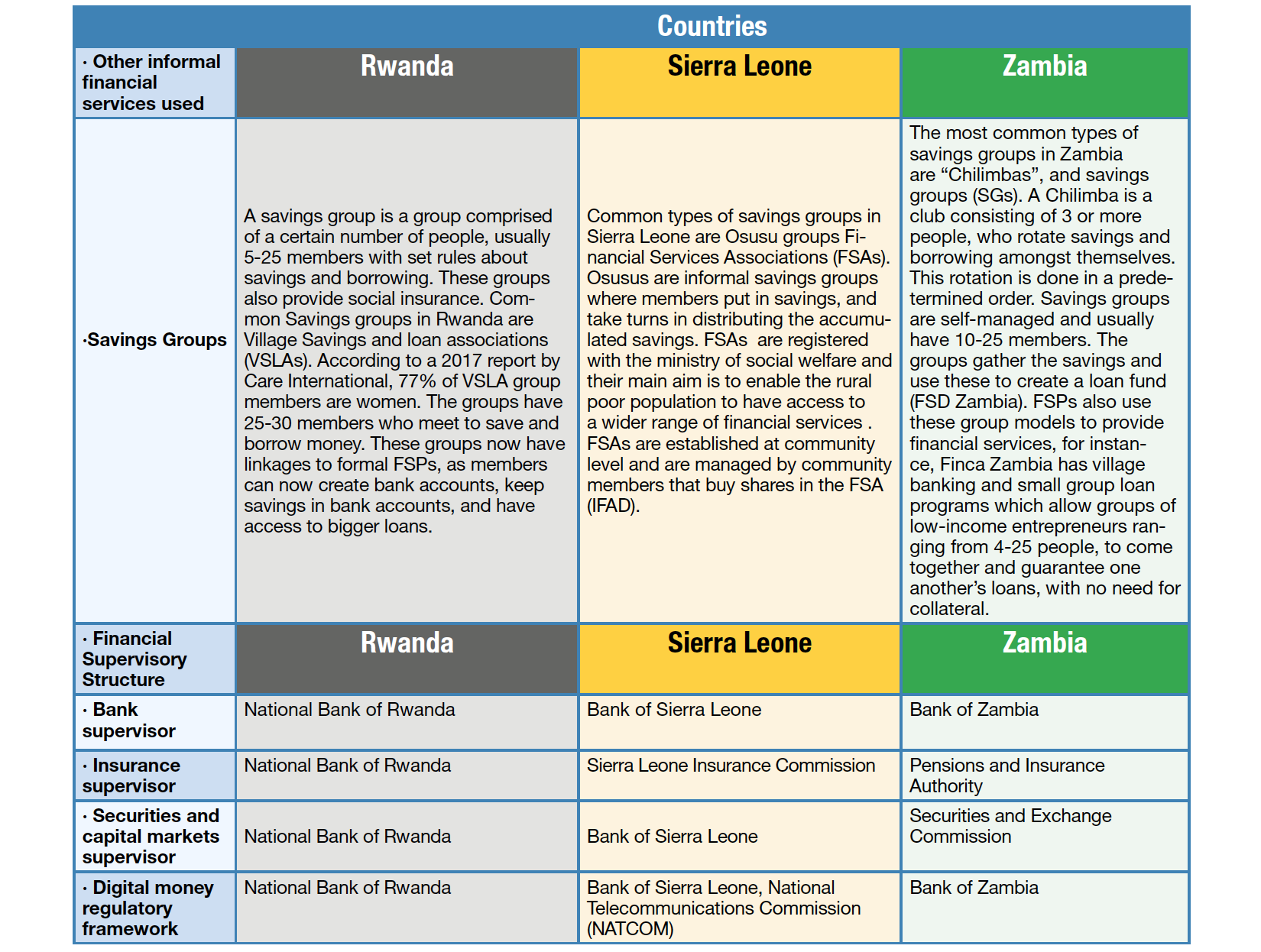

Phase 1 – focused on secondary research to understand the financial inclusion landscape with findings mostly reflected in Annex 3 Country Reports. Furthermore, the desk research explored issues around the impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods and financial inclusion in general.

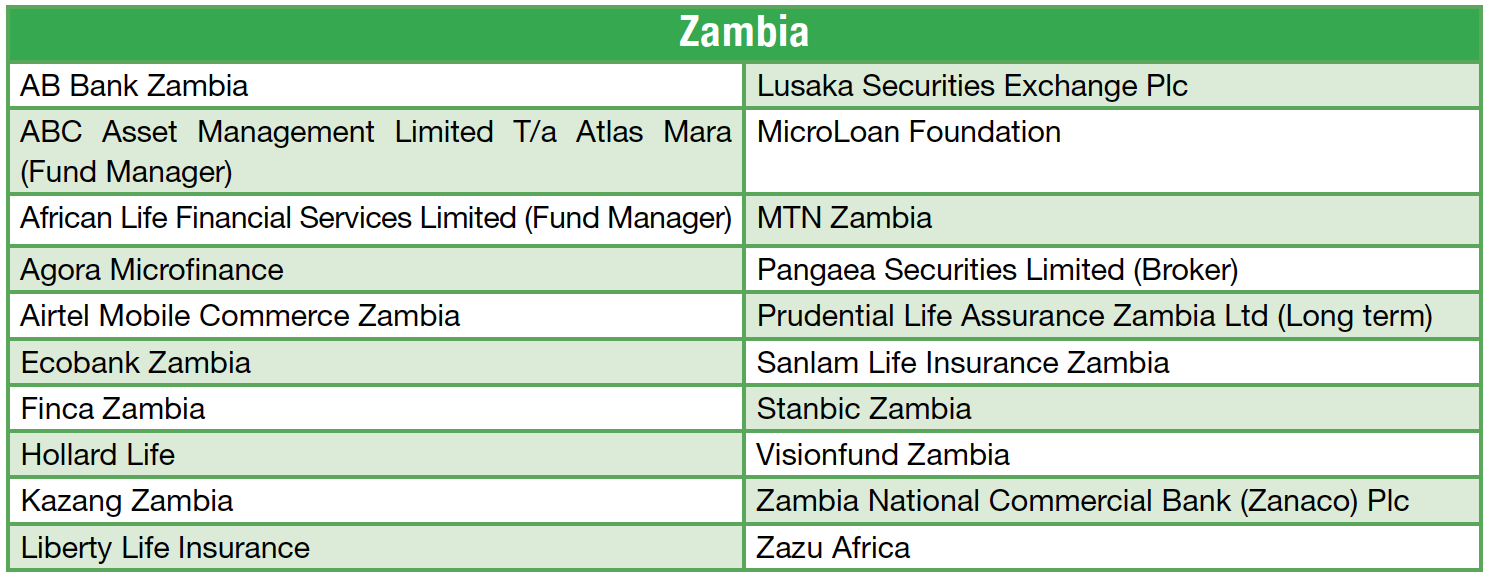

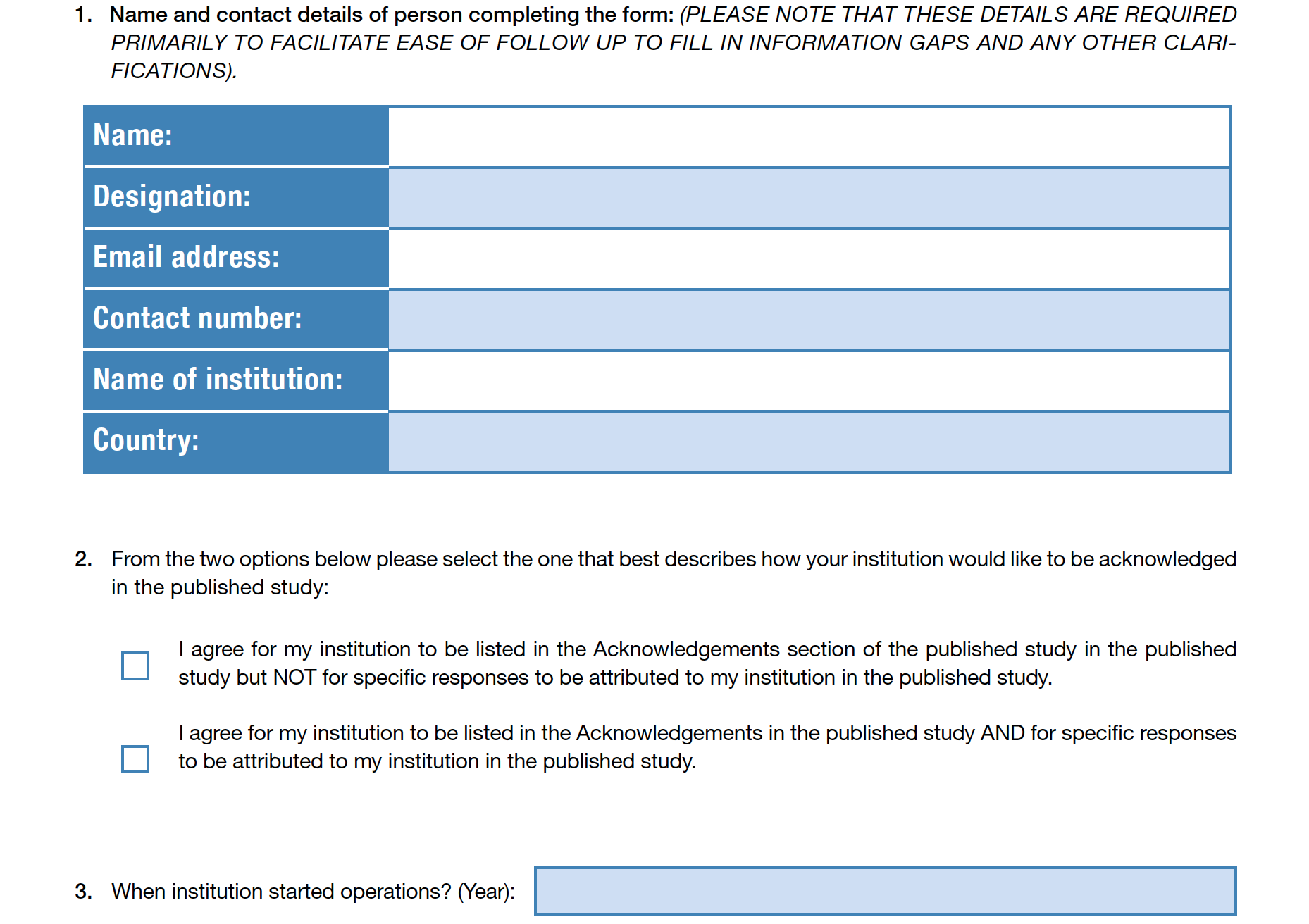

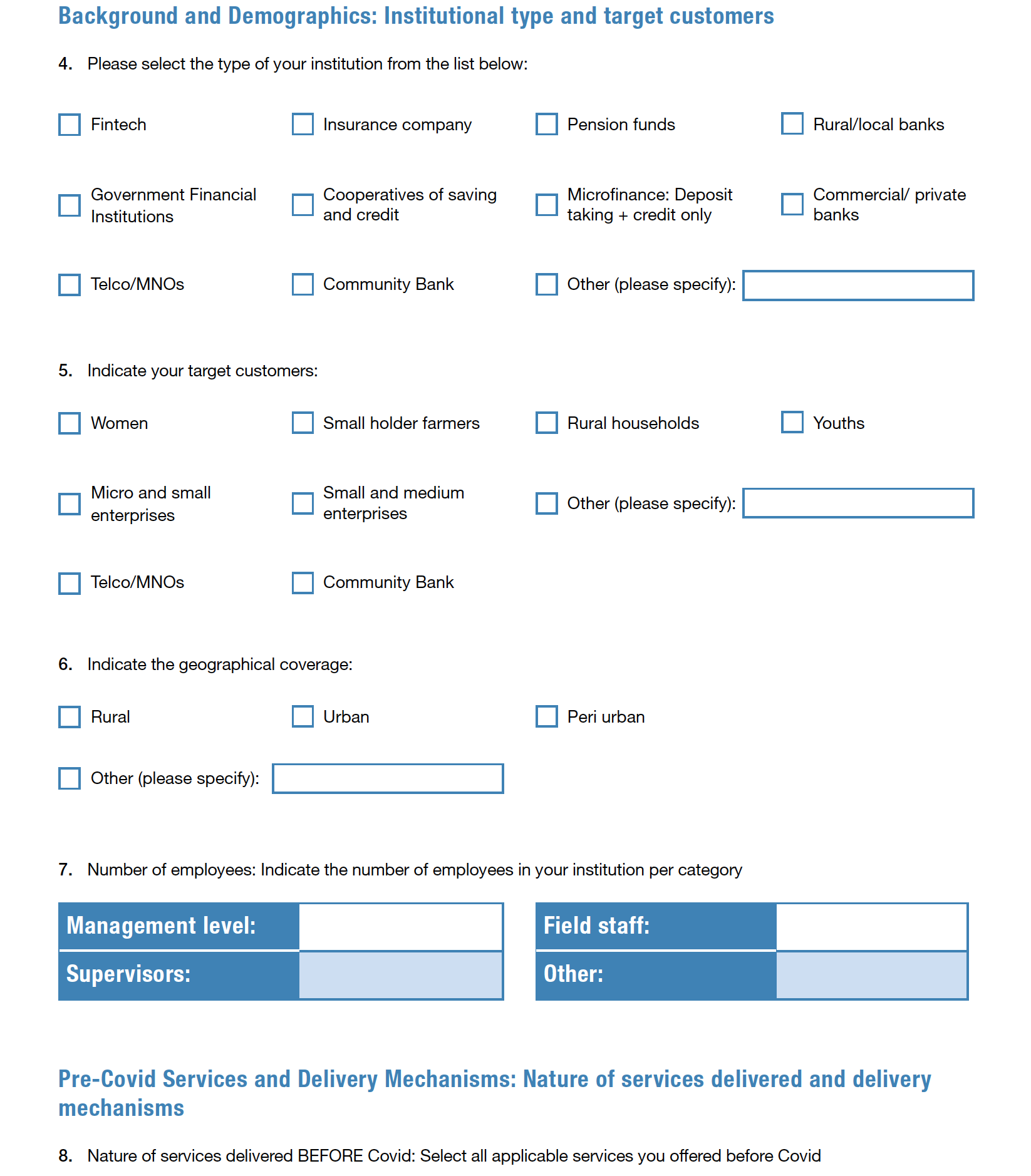

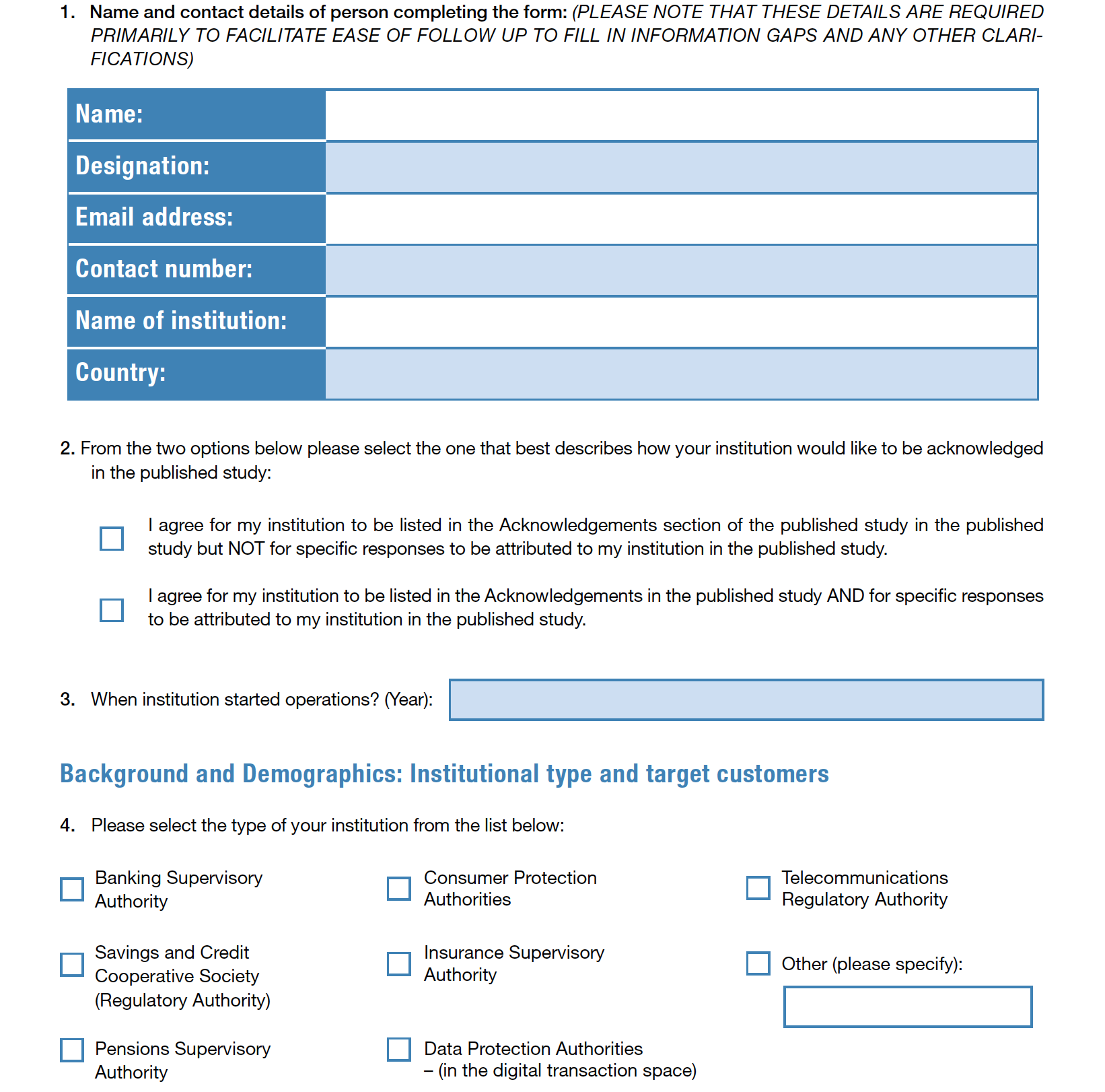

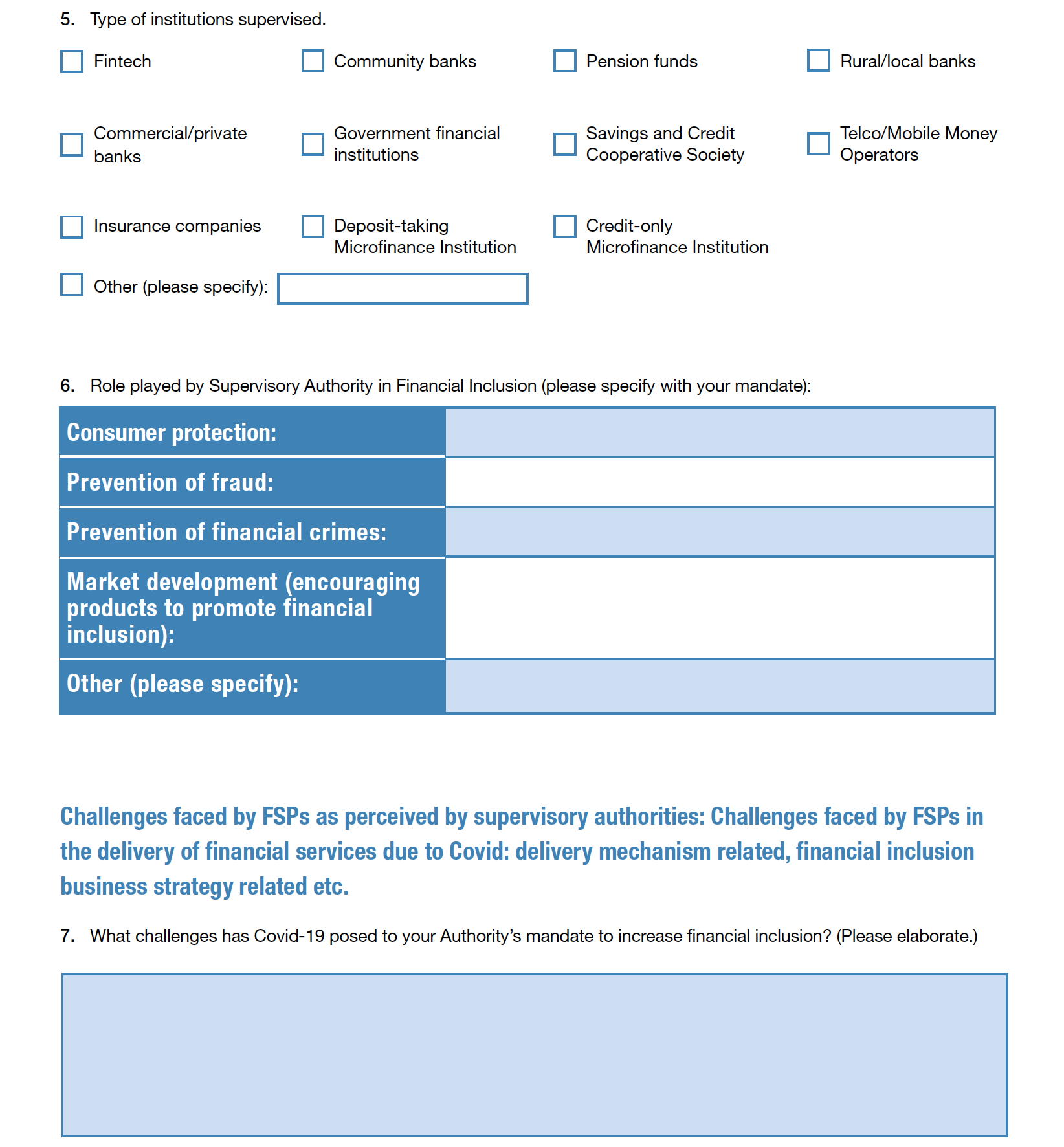

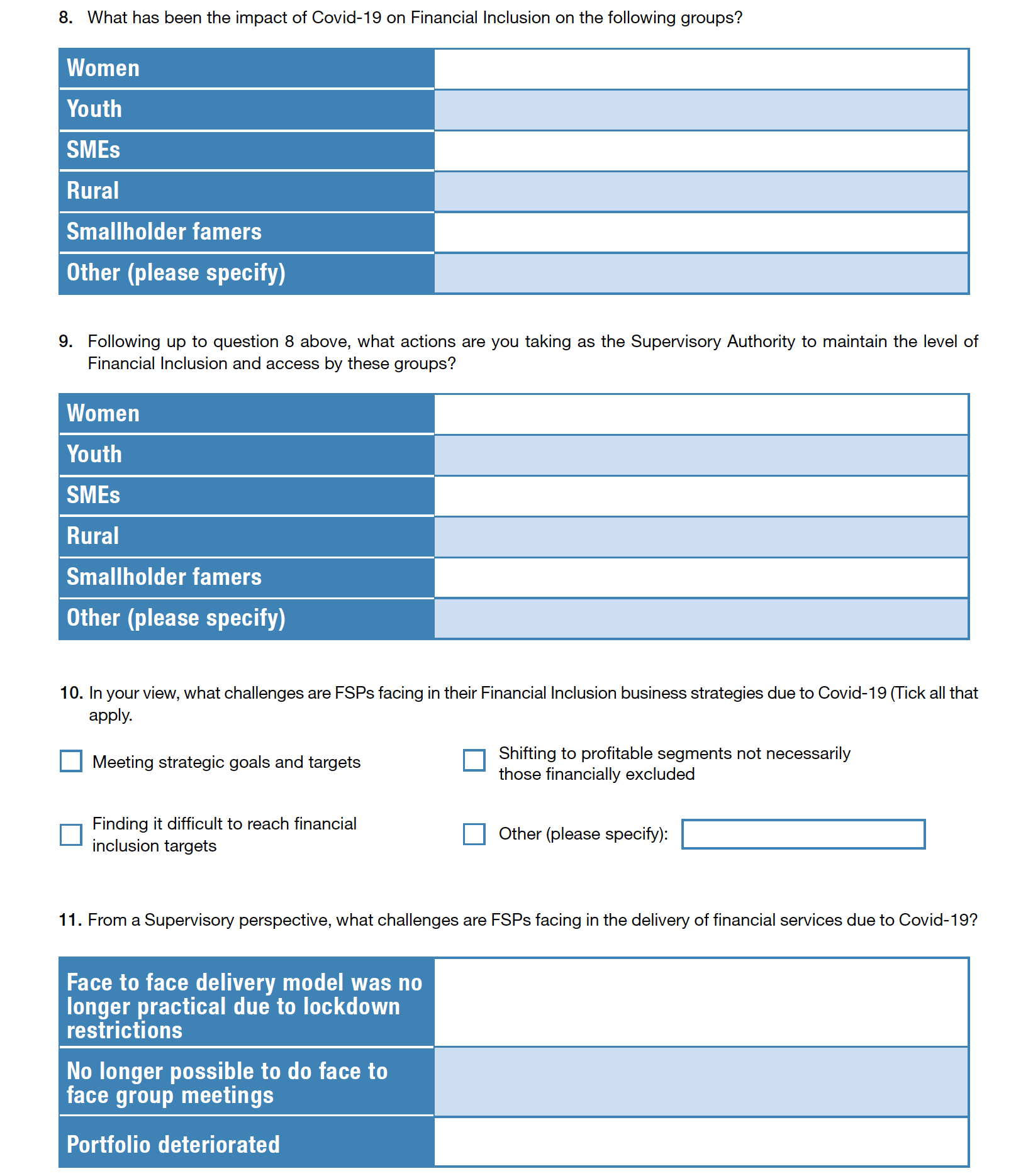

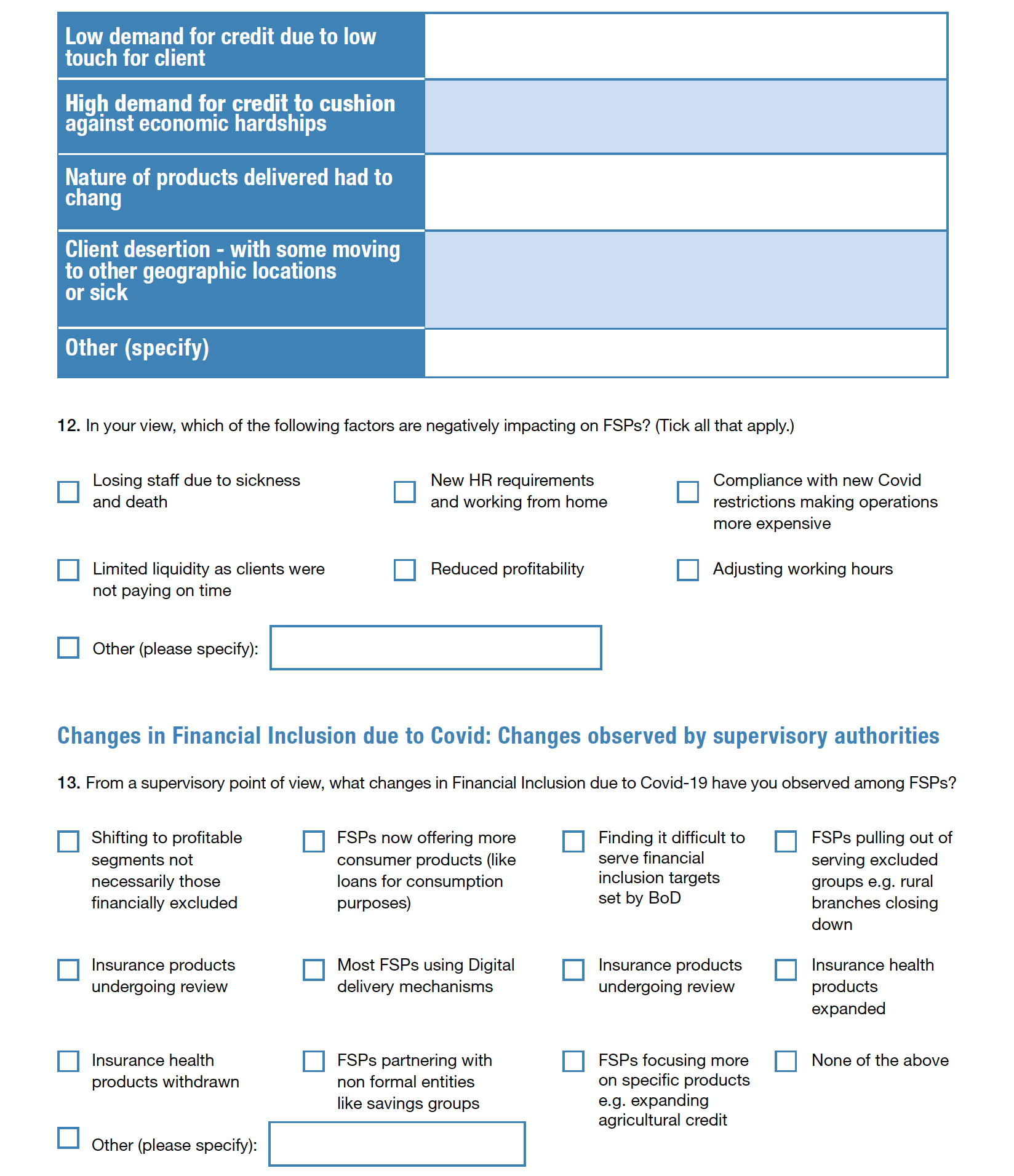

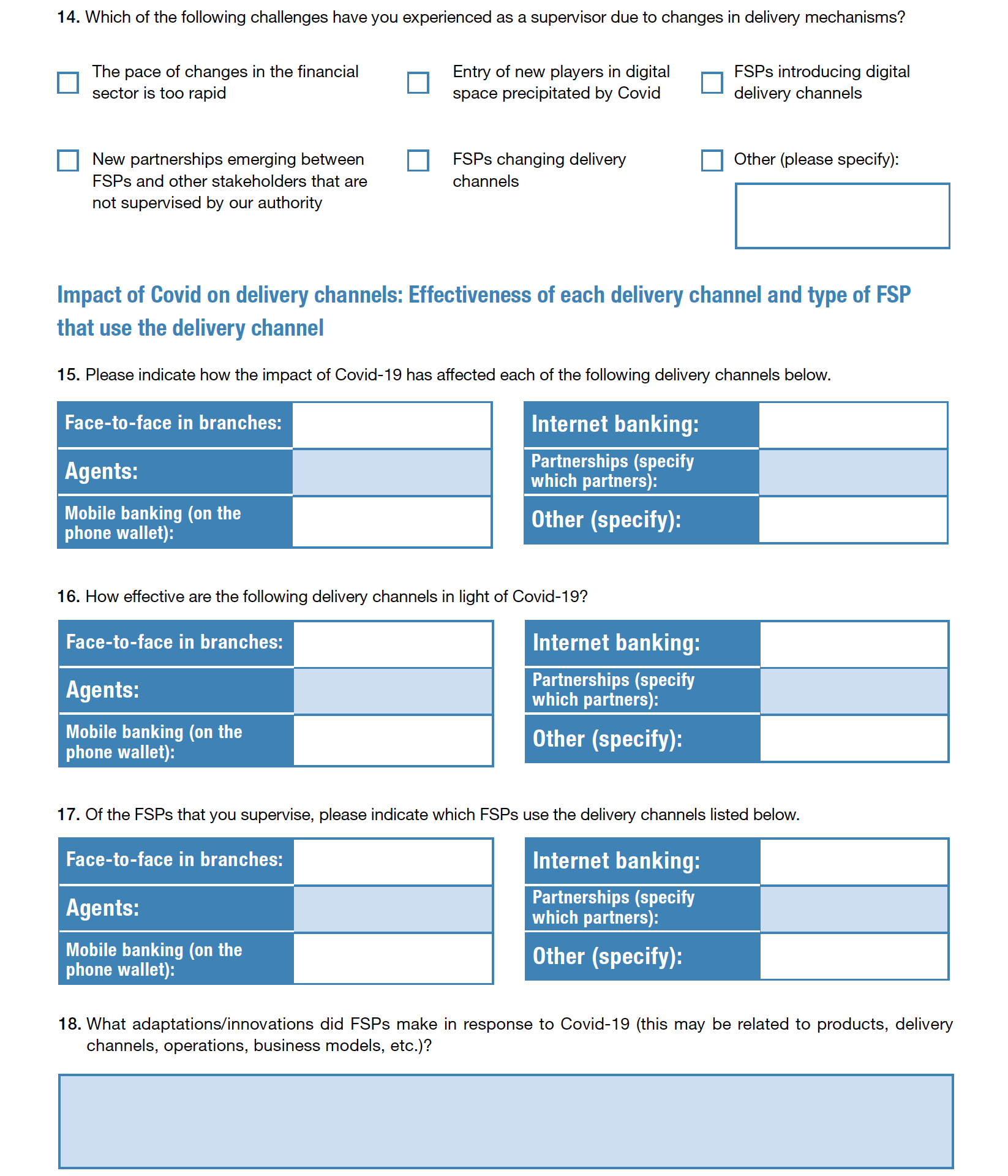

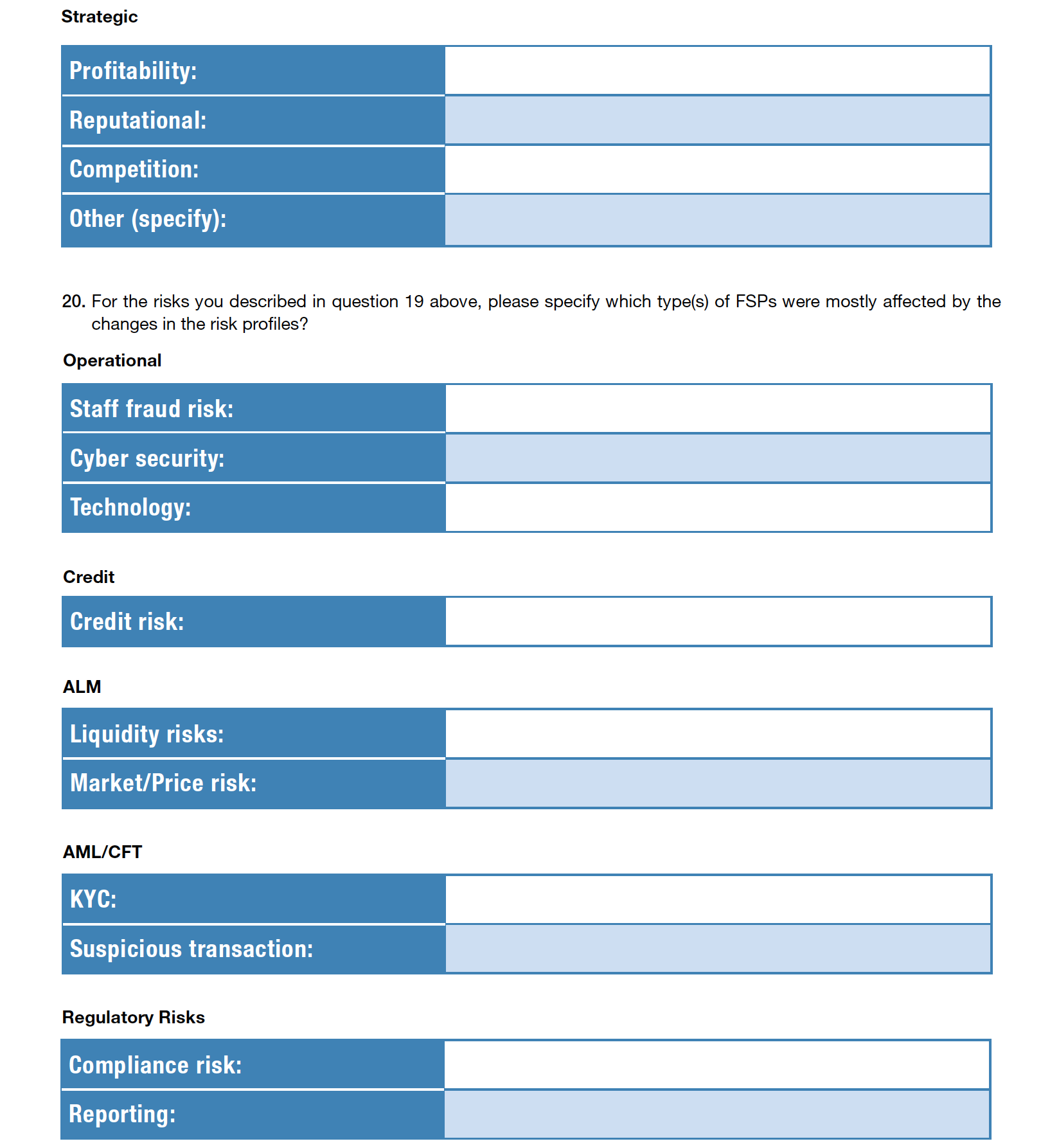

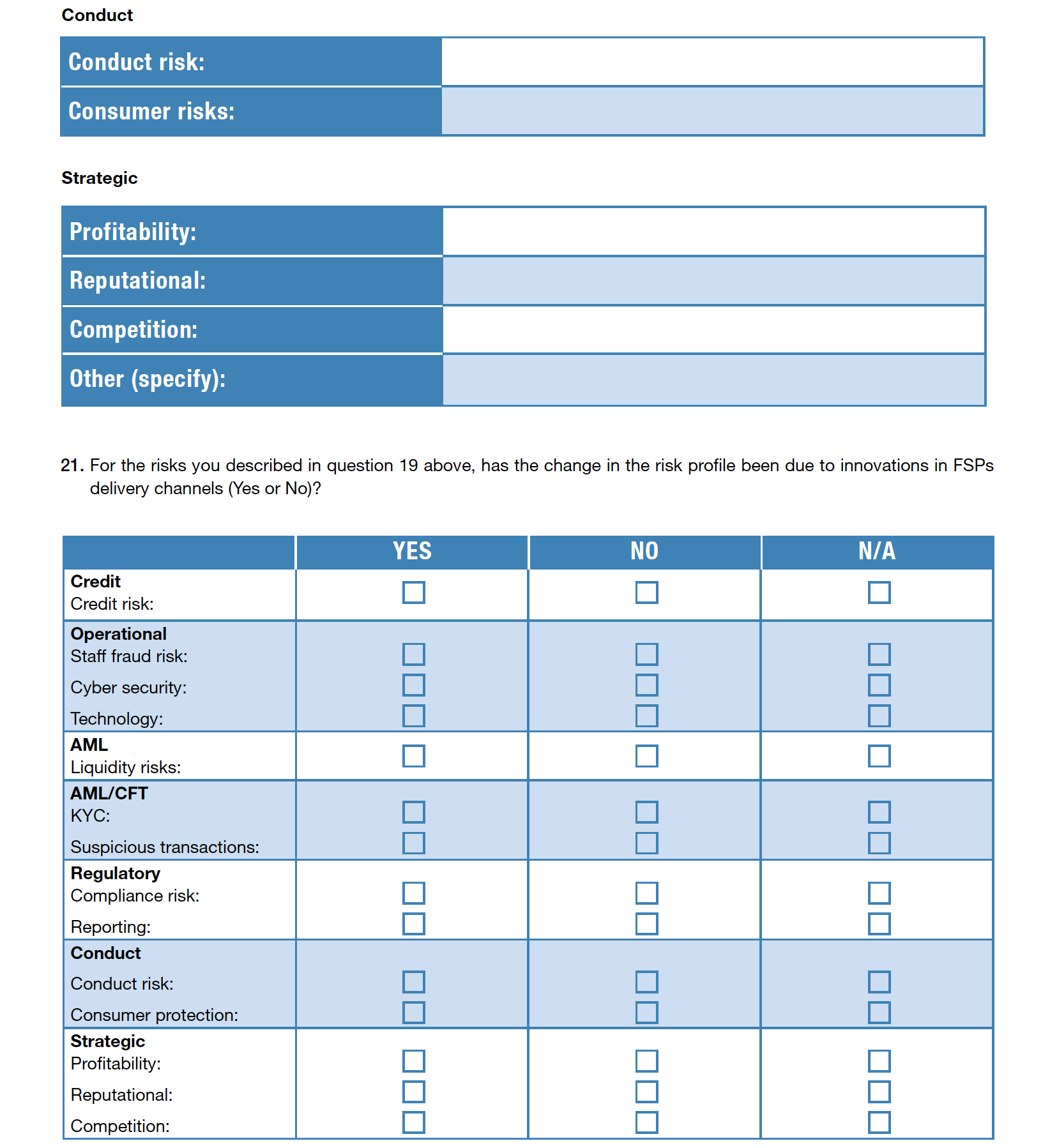

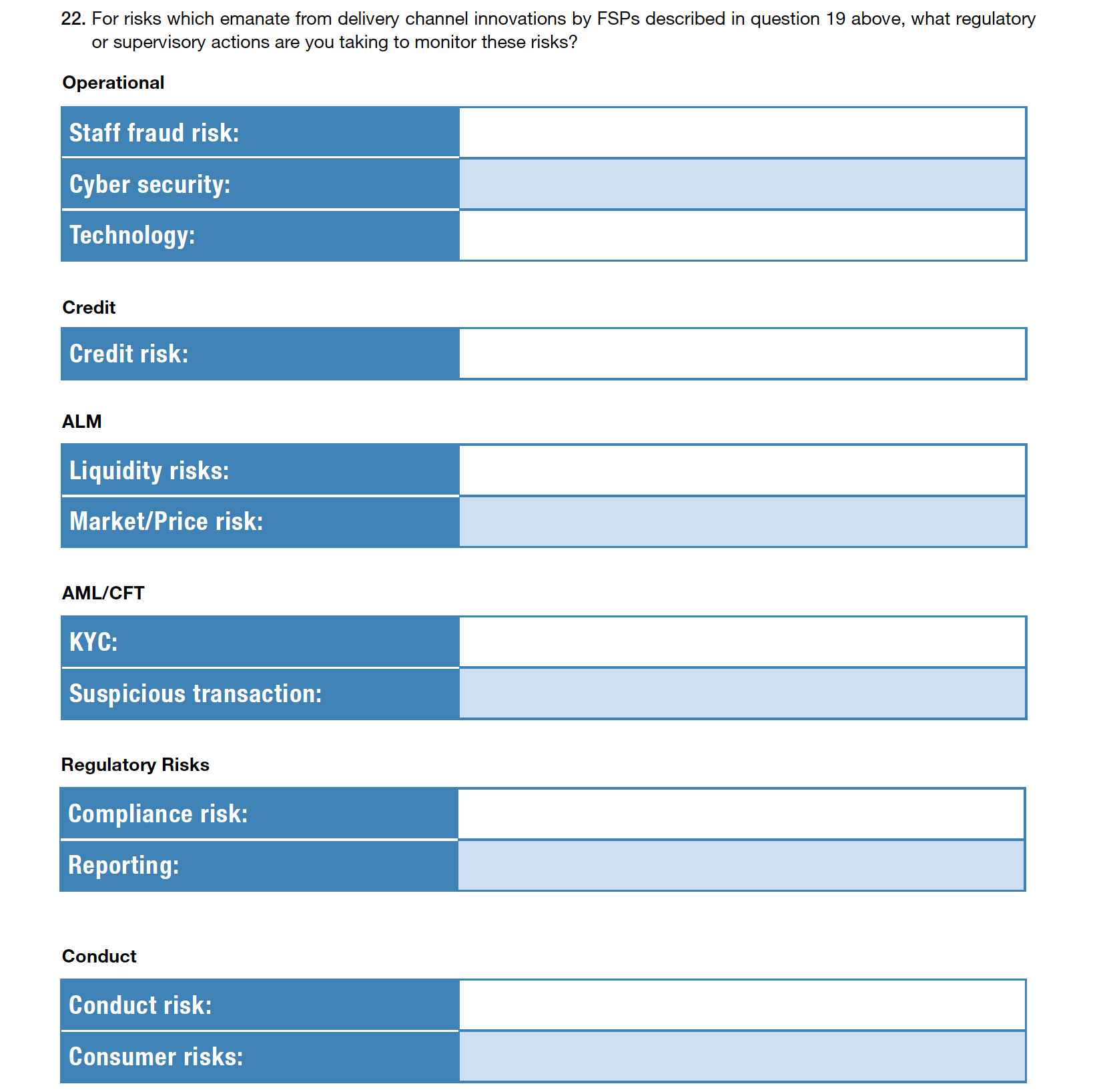

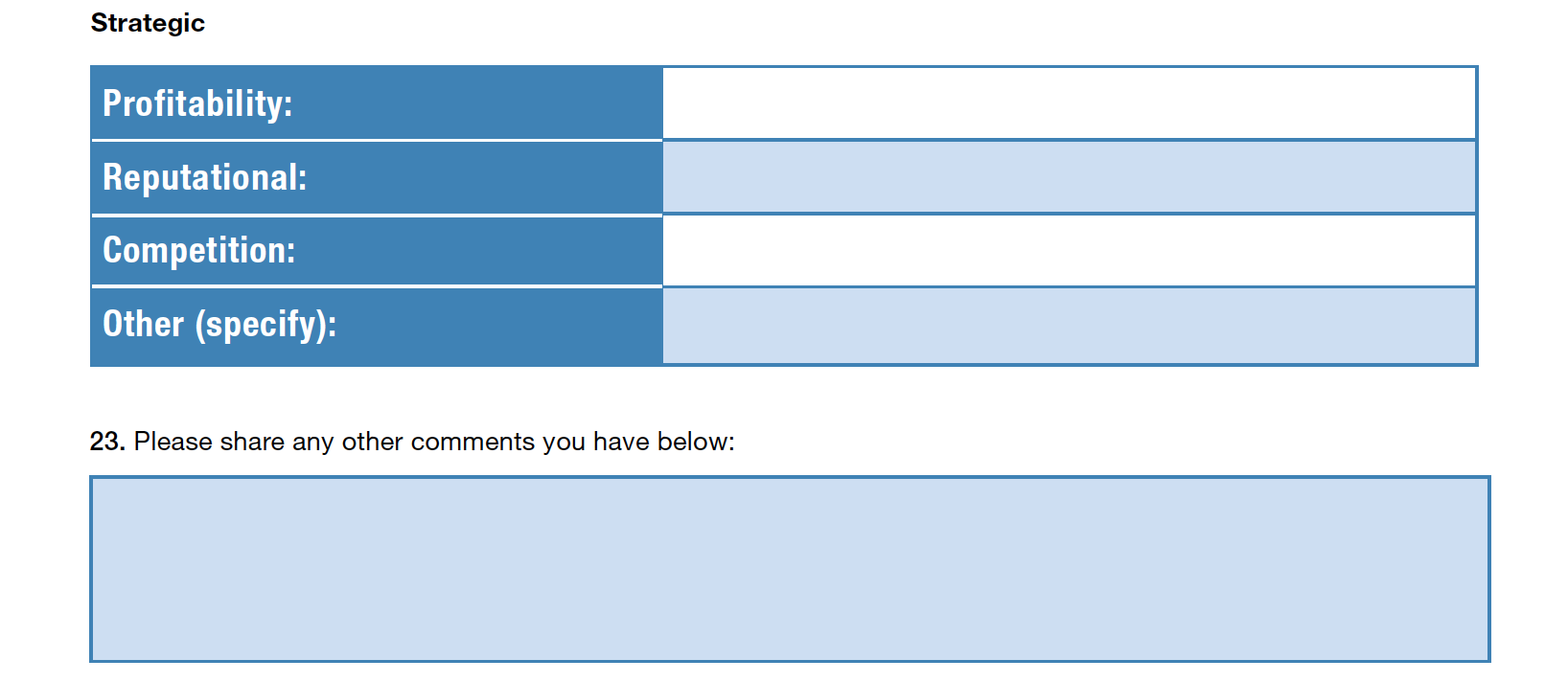

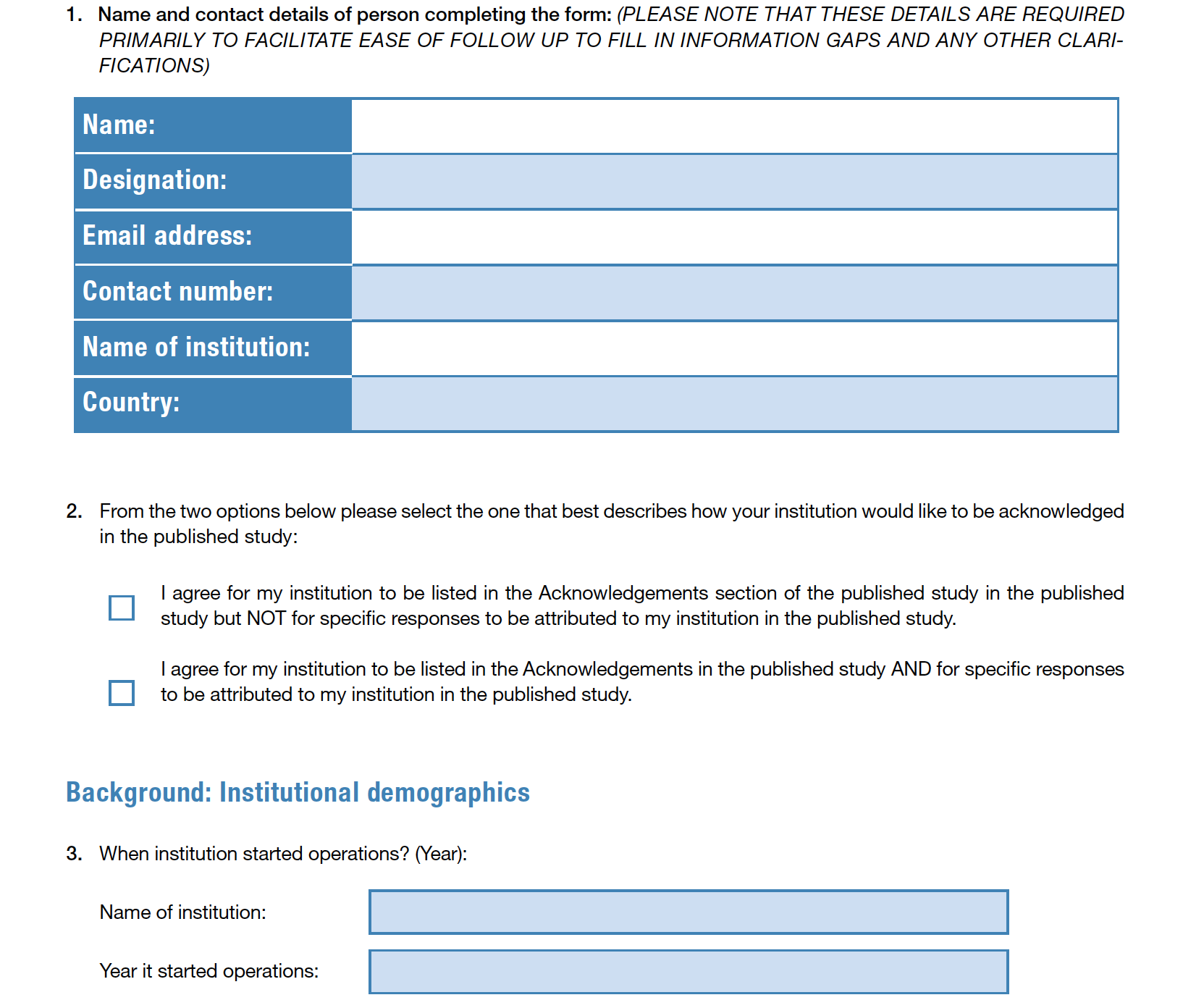

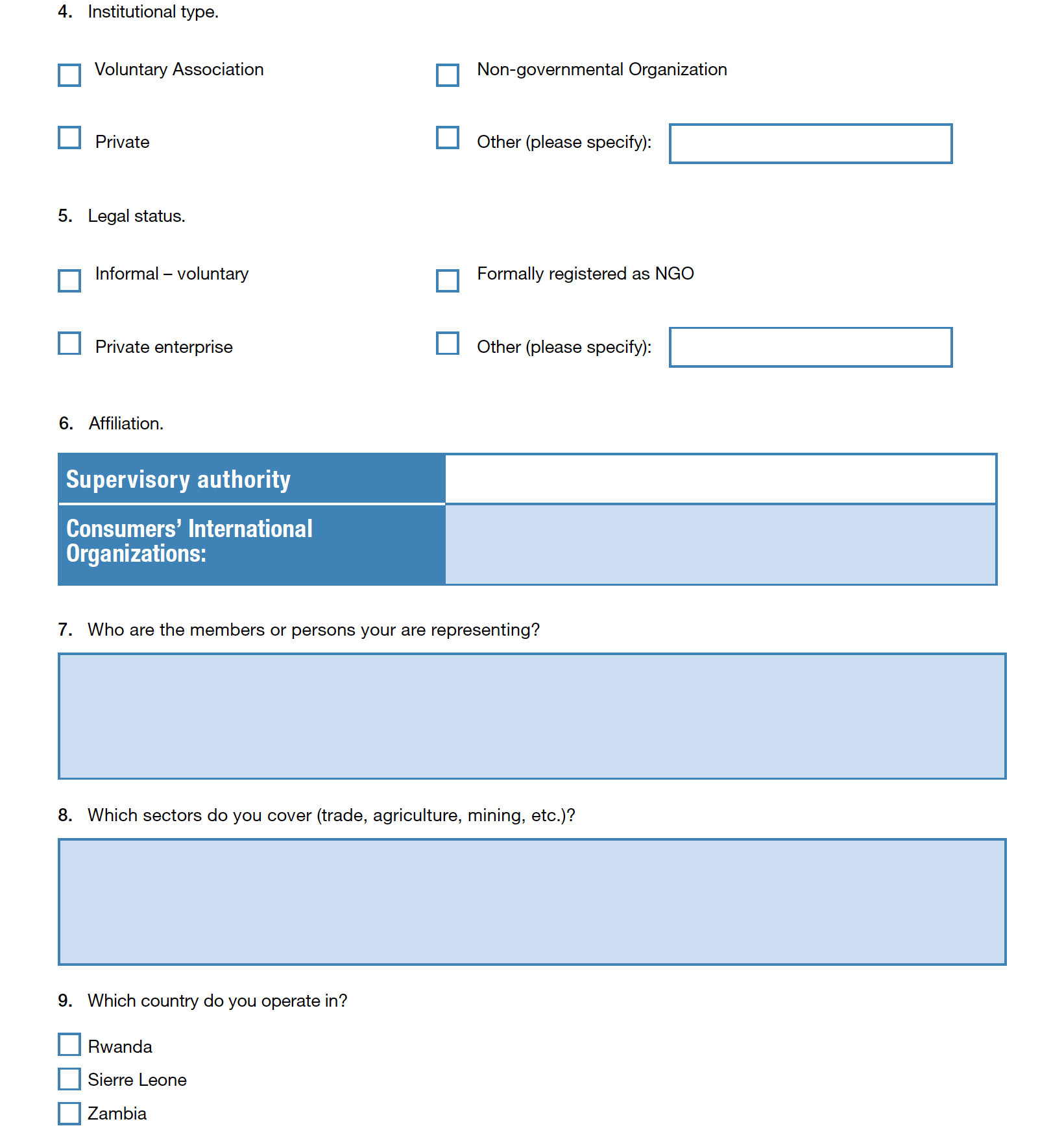

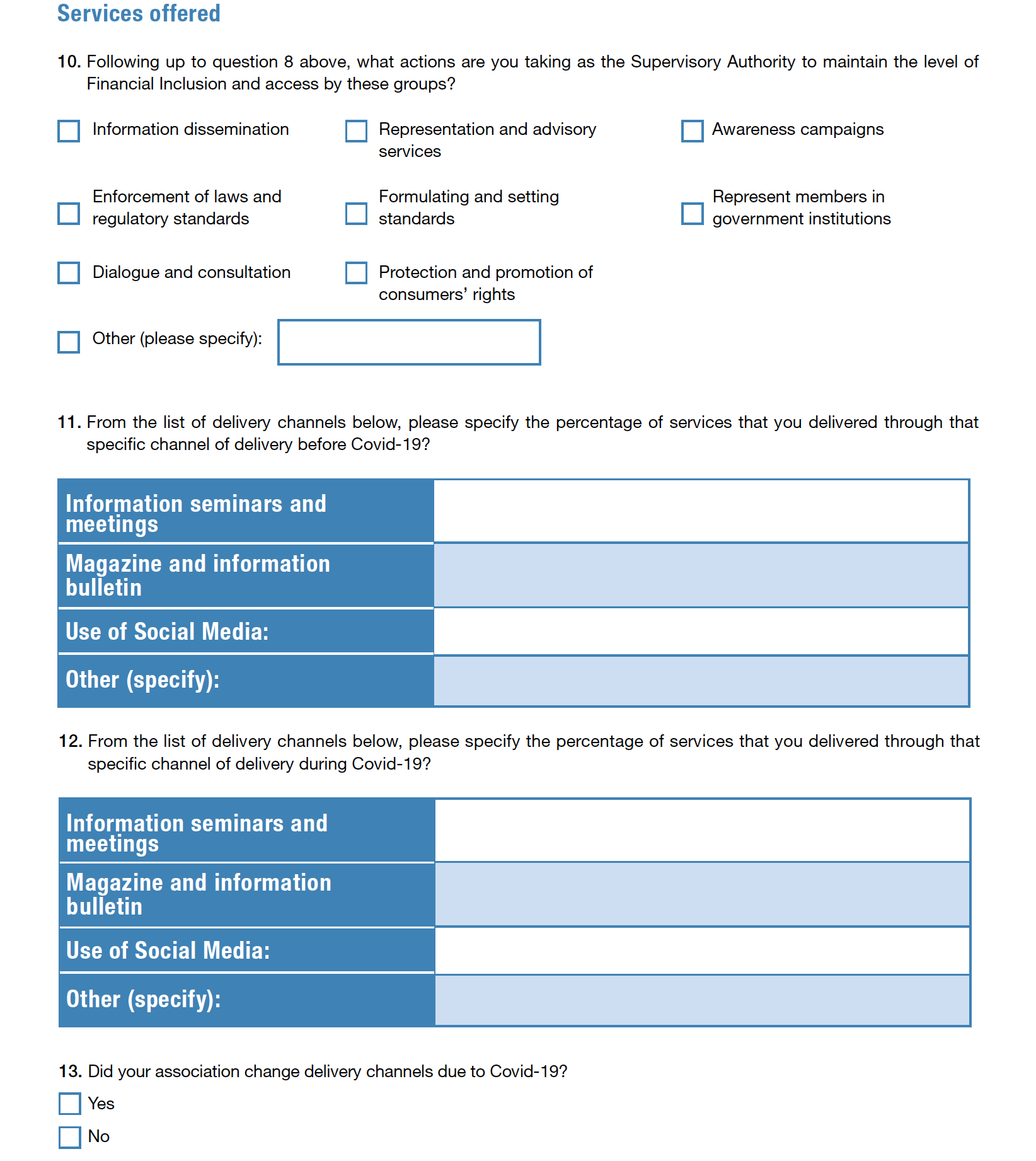

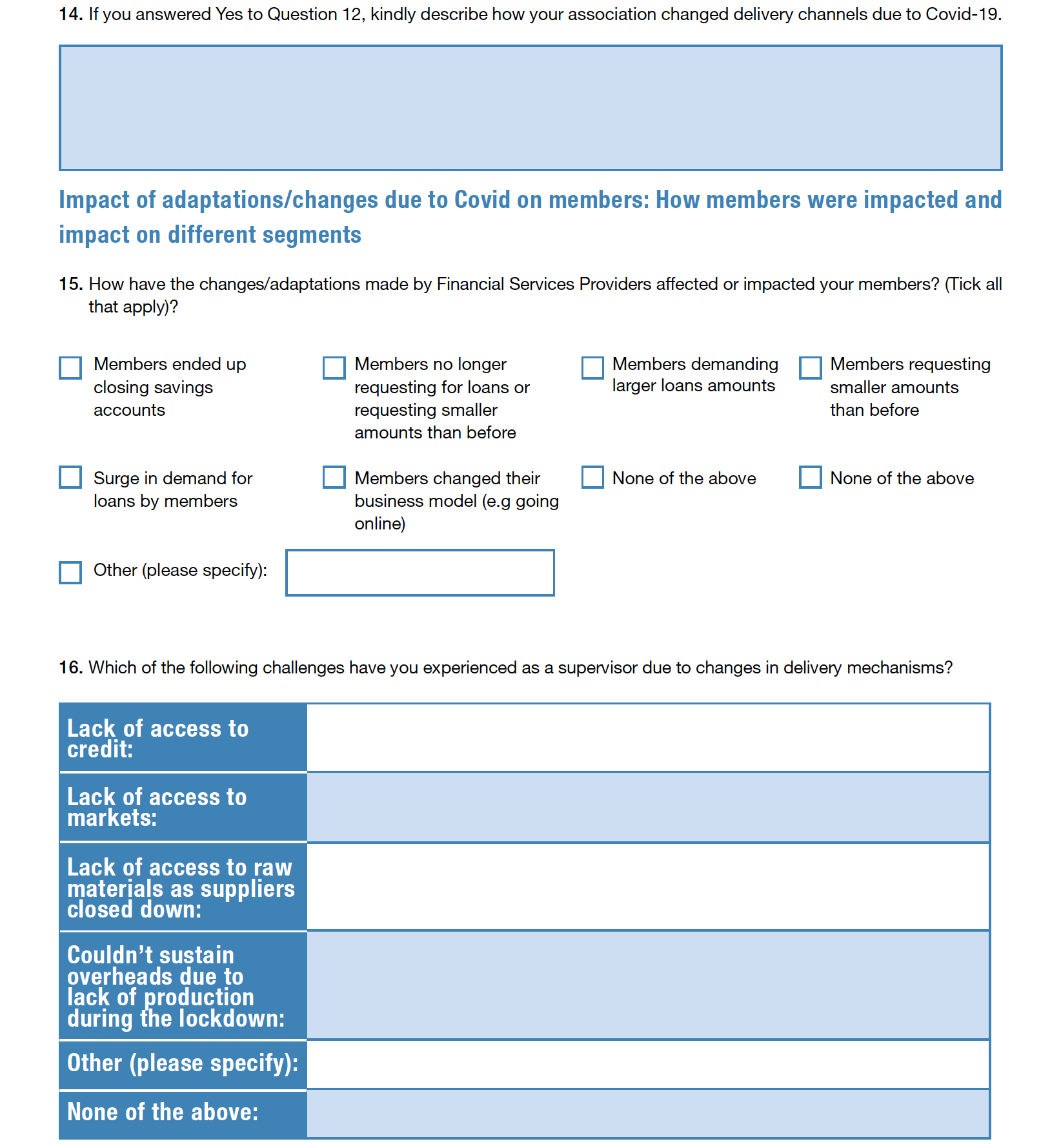

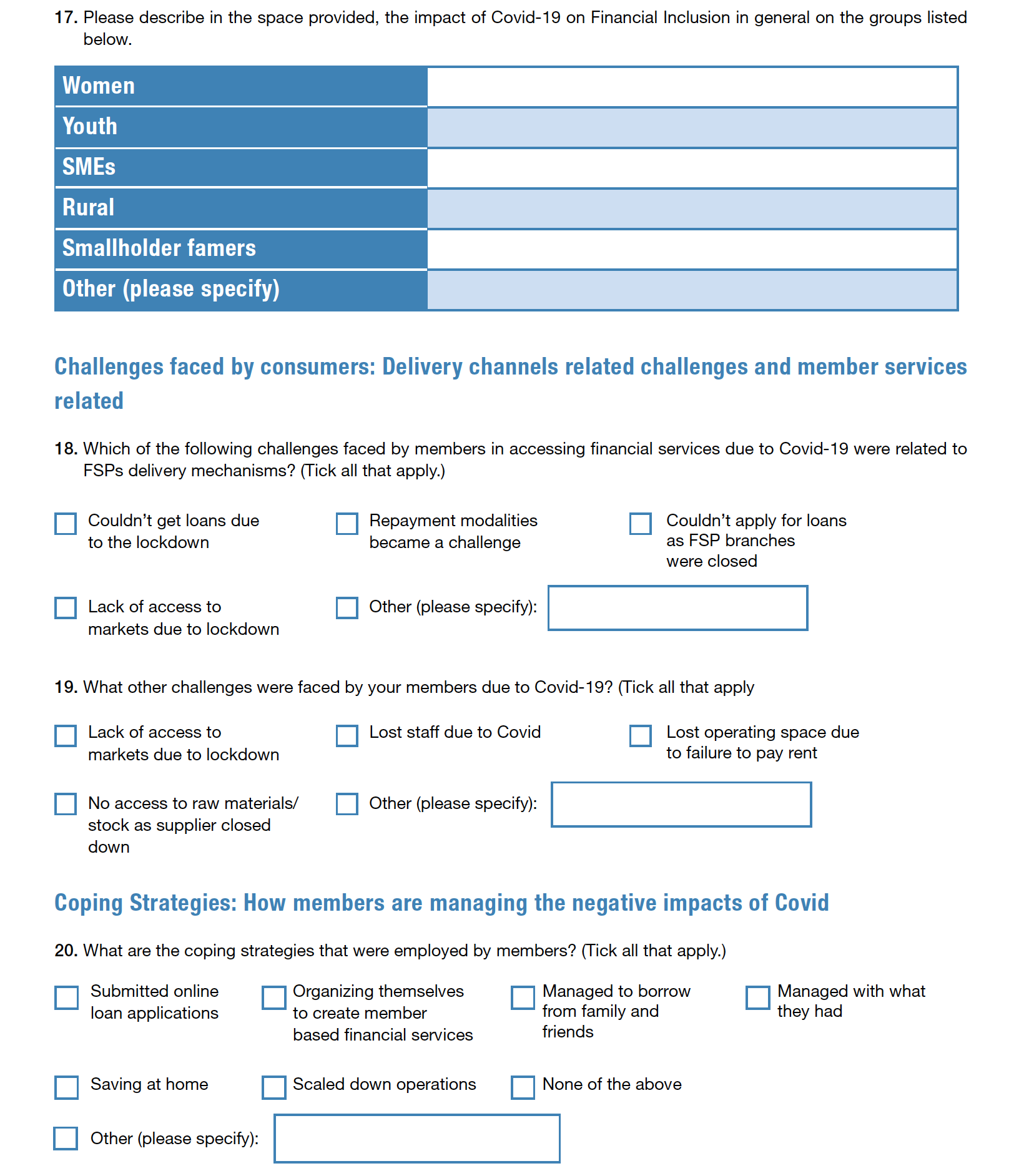

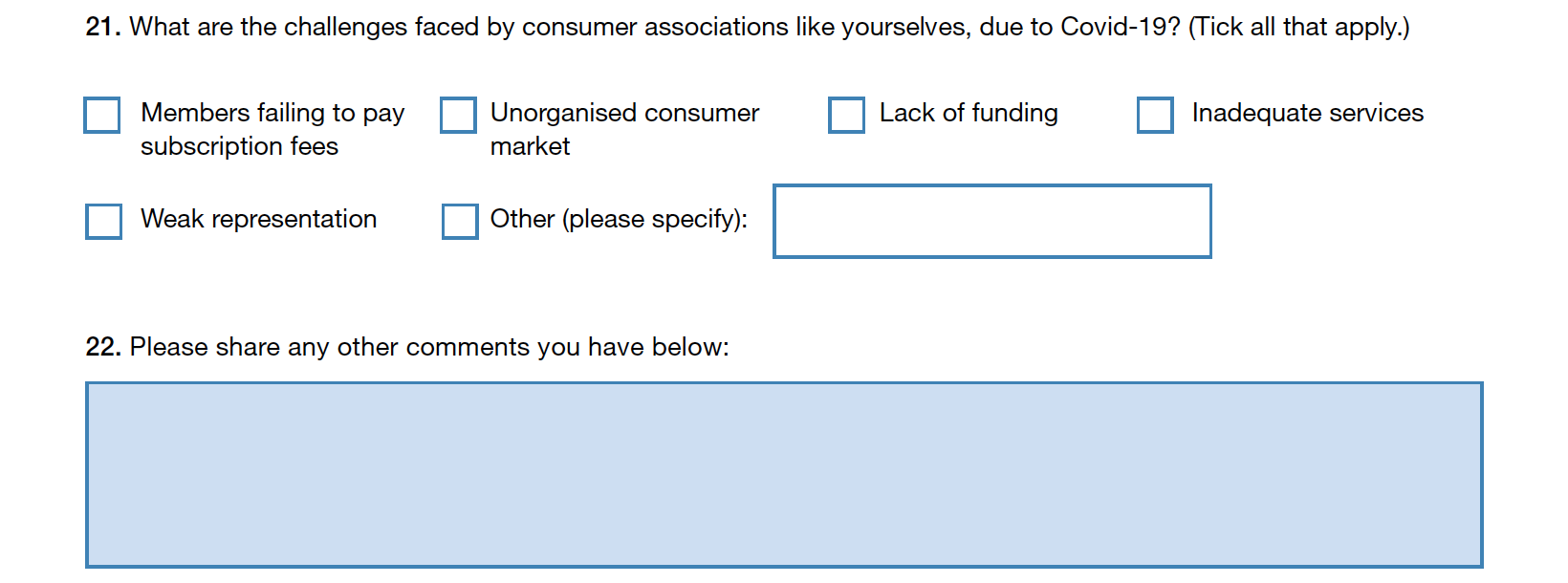

Phase 2 – involved an online survey using SurveyMonkey (see Annex 2 Survey Instruments) that was conducted from January to February 2021 in the three countries with financial supervisors, FSPs and associations of consumer groups. Each respondent group received a separate questionnaire. The FSP respondents were purposefully selected via discussions between the TC team and financial supervisors in each country.

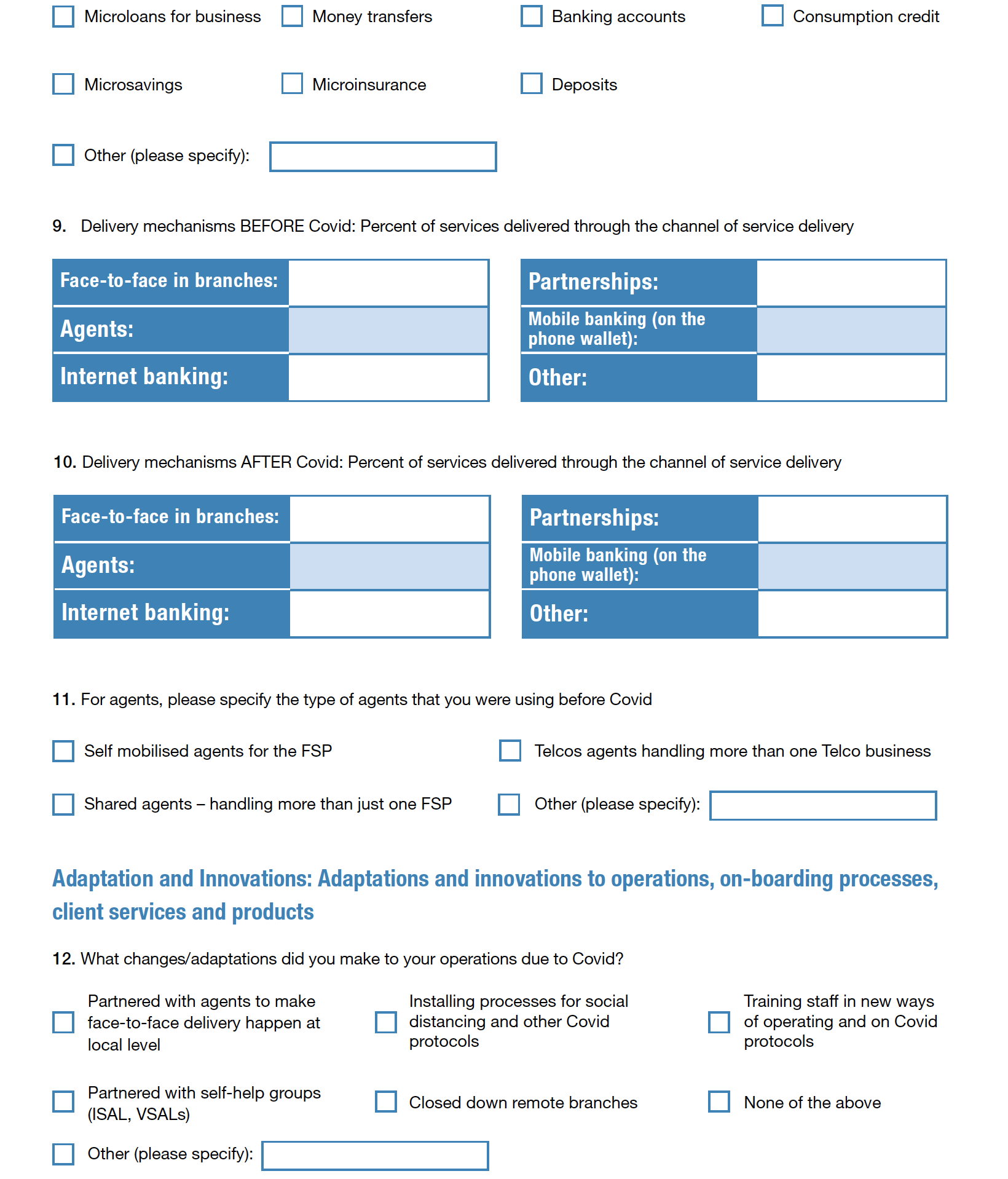

The purpose of the survey was to explore the study hypotheses to understand how FSPs had responded to COVID-19, especially in their delivery channels. Key questions focused on whether or not F2F delivery was still the main delivery channel for financial services. If F2F was still dominant, the survey then sought to identify how FSPs had adapted to the COVID-19 protocols. If it was not, the survey sought to find out which channels had replaced F2F.

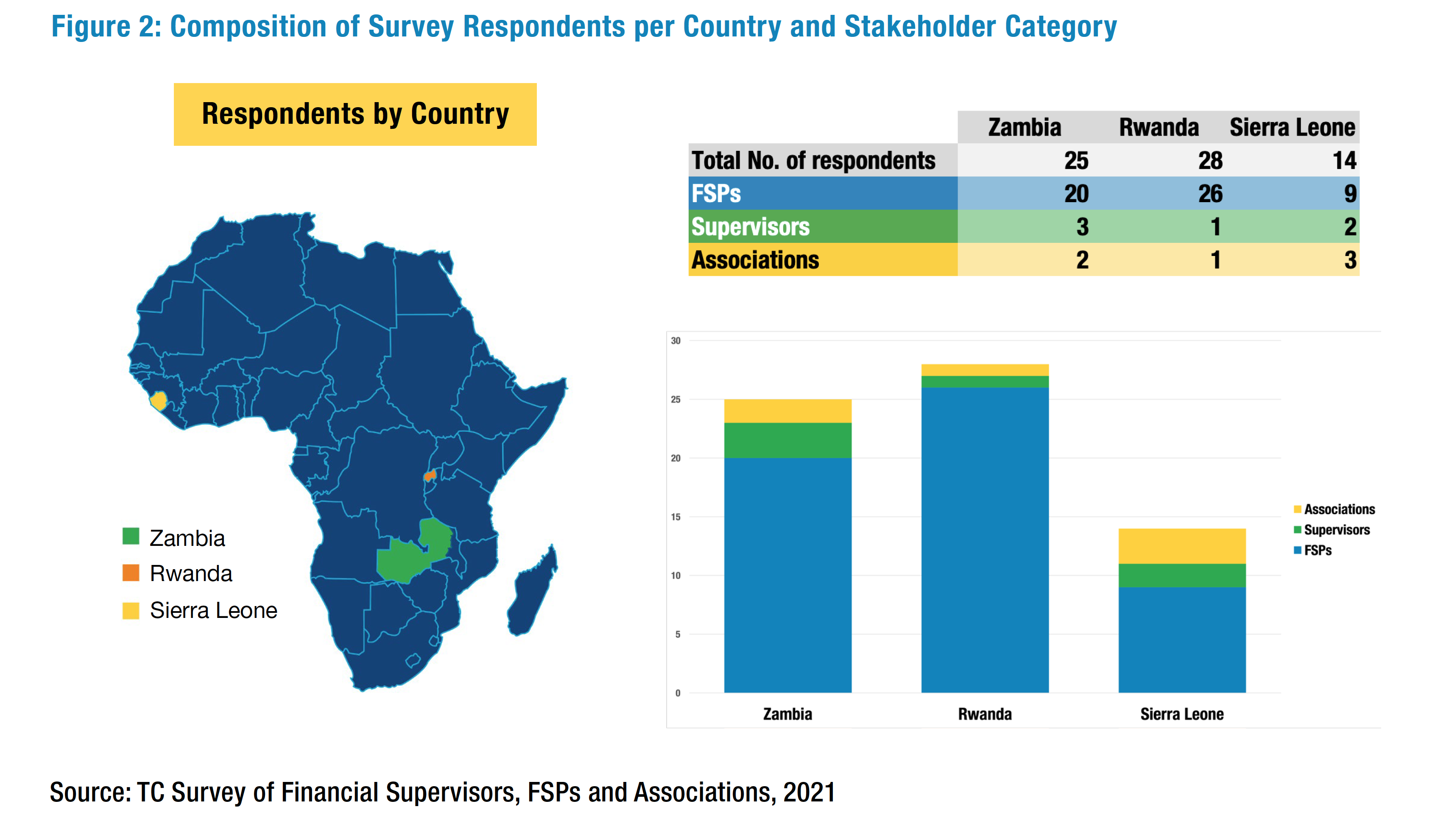

There were a total of 67 responses to the online survey. The composition of survey respondents is shown in Figure 2 below.

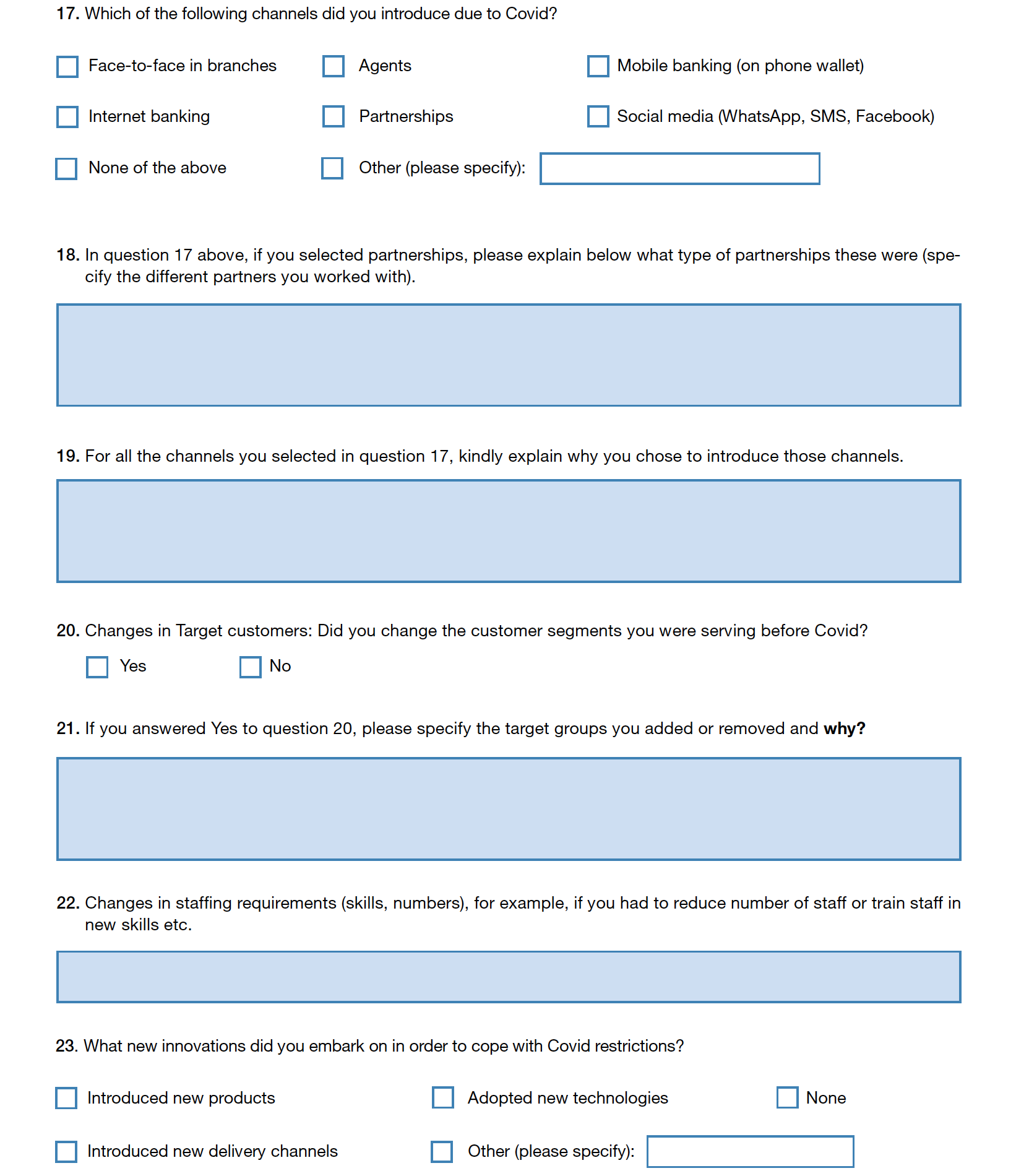

Phase 3 – the preliminary survey findings framed the agenda for the two webinars. The first was held in April 2021 with financial supervisors, and the second took place in May 2021 with FSPs from the three countries. The webinars allowed for in-depth discussions between the research team and the stakeholders on key topics: for example, how financial supervisors perceived the changing financial risk landscape in each of their countries and how they were responding to these changes. Most of the webinar discussions with the FSPs focused on how the changes they made affected their customers, including the vulnerable groups, and how their risk profiles had changed.

Phase 4 – focused on following up on innovative strategies employed by various FSPs and/or supervisors in different countries as they sought to cope with the effects of COVID-19 and/or the heightened risks. In-depth interviews were conducted with various stakeholders and provided the information contained in the case studies in this report.

2.1 PROFILE OF FSP SURVEY RESPONDENTS

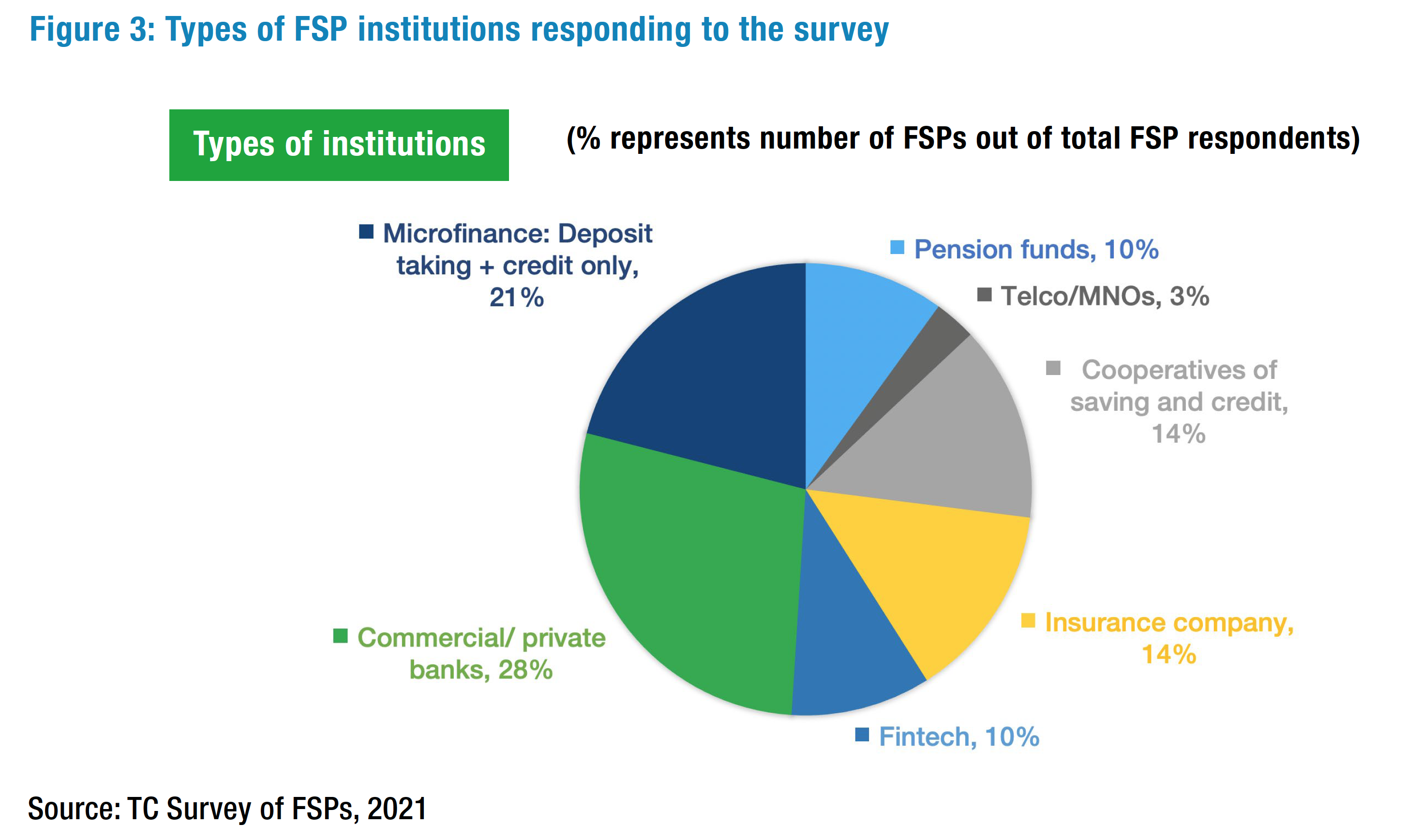

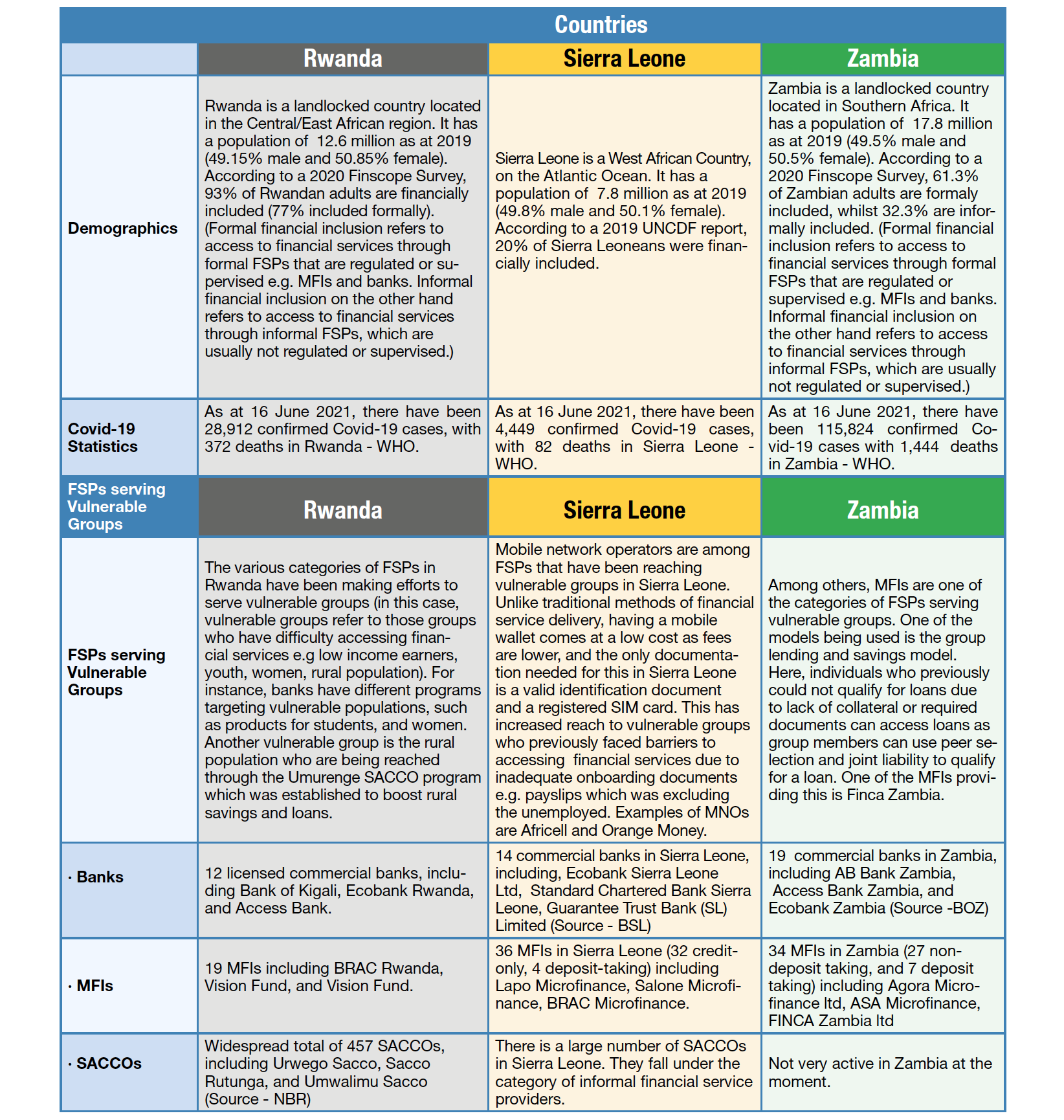

The FSPs in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia selected for the survey were representative of FSPs by their size, type, and the financial services offered to financially excluded groups in that country. The breakdown by types of FSP institutions for all three countries together was: commercial/private banks (28% of the total number of institutions); microfinance institutions – both deposit taking and credit only (21%); cooperatives of savings and credit (14%); insurance companies (14%); and FinTech companies (10%). Telcos and Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) that offered financial services comprised 3% of respondents by the number of institutions (see Figure 3).

In all three countries, all financial supervisors responsible for supervising the FSPs responded to the survey. These were: the National Bank of Rwanda, which covers all FSPs including insurance; the Bank of Sierra Leone and the Sierra Leone Insurance Commission; and the Bank of Zambia, the Zambia Pensions and Insurance Authority and the Zambia Securities and Exchange Commission.

The category “Other”, with 10% of respondents as set out in Figure 3 above, comprised of other stakeholders that are either industry or consumer associations or fit into more than one category. For example:

Rwanda

- Microfinance Bank

- Association of Microfinance Institutions in Rwanda

- Brokers Association - association for all brokers in Rwanda

Sierra Leone

- Mobile Money Operators (MMOs): respondents self-identified as “other” rather than as MNOs.

Zambia

- Financial Advisory and Securities Brokerage

- Investment Management

- Securities Exchange

2.2 PRE-COVID BASELINE: CUSTOMER SEGMENTS SERVED AND FINANCIAL SERVICES PROVIDED

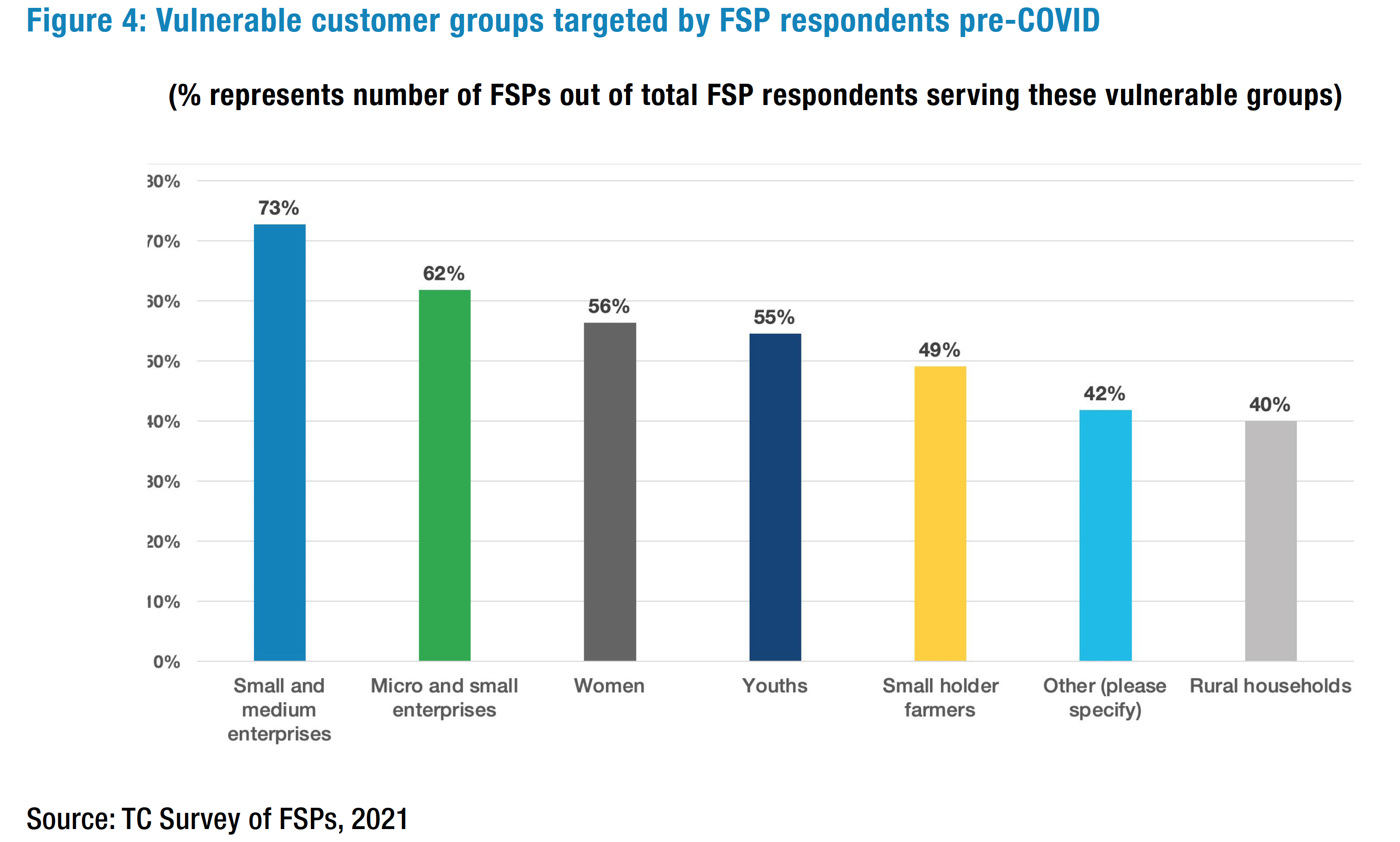

The survey first sought to establish a baseline on which financially excluded customer groups were targeted by the FSPs before the pandemic. Figure 4 shows that over two thirds (62% to 73%) of the FSPs surveyed in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia were serving micro, small and medium enterprises prior to COVID-19. The number of FSPs serving other vulnerable populations in the target countries pre-COVID ranged from 49% (smallholder farmers or SHF), 55% (youths) to 56% (women). Only 40% of surveyed FSPs served rural clients pre-COVID. ‘Other’ vulnerable customer groups served pre-COVID included the low income mass market customer segments and refugees served mostly through offering mobile money services, especially in Rwanda.

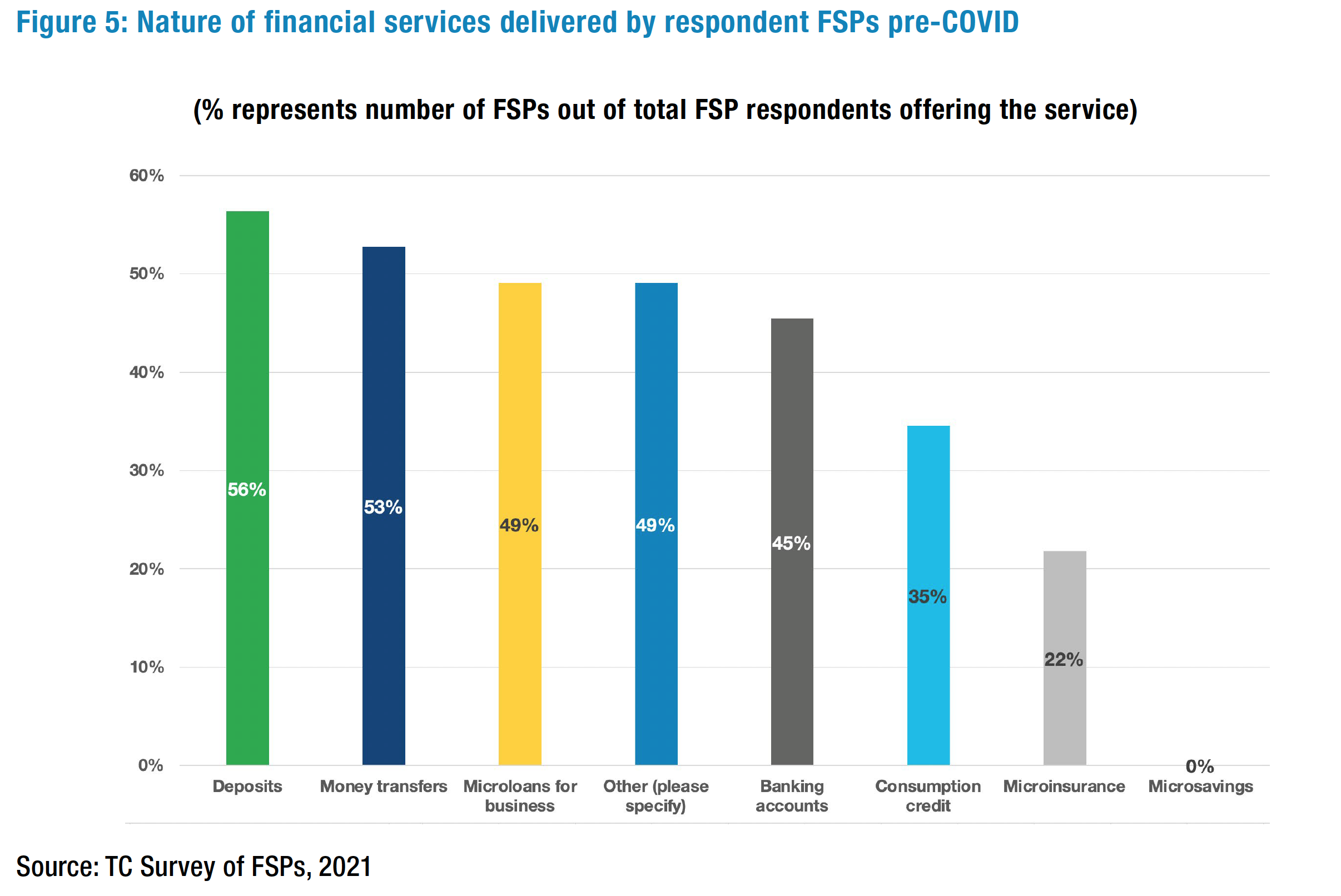

As a baseline, the survey also asked FSPs what financial services they were offering pre-COVID. Figure 5 shows the top or most commonly offered categories of financial services offered by the FSPs, with the “Other” category captures typical traditional banking products such as current accounts, fixed deposits, Bancassurance (loan protection and fire protection), bank guarantees, government payment collection, and overdrafts. While the latter categories of traditional financial services are not specifically aimed only at financially excluded customer groups, there are some financial services such as money transfers, microloans for businesses, consumer credit, and micro insurance, that are typically products for financially excluded groups.

Other non-financial services that FSPs offered to these vulnerable groups included financial literacy outreach, cited by a few FSPs especially from Zambia and Rwanda. Since financial literacy levels are generally low among the financially excluded groups, some FSPs have branded financial literacy training as one of the “gateway” services they are offering to clients and potential clients. For instance, the ‘Anakazi’[2] banking scheme created by Stanbic Bank Zambia is a product meant to support female-led services. This scheme opens up access to financial resources and knowledge management. Through the Anakazi scheme, women have access to services such as financial education, business mentorship, savings and credit. For those financially excluded groups, a package of non-financial services is required to address the barriers to inclusion, which may be lack of education, or business management skills – hence creating a market that is ‘investor ready’. According to the FSPs, empowering the excluded groups is one effective way of enabling them to use the financial services offered by the FSPs.

Other products were cited in Rwanda where, besides the gateway products of savings and loans, FSPs also offered microloans for agriculture, hospital cash products, and loans for refugees. In Zambia, FSPs also offered services, such as selling electricity and airtime for MNOs, making such payment services accessible to financially excluded groups such as women working in local markets and SMEs.

Thus, respondent FSPs were already offering a wide range of financial and non-financial services to financially excluded groups as a business before COVID-19, therefore actively contributing to the promotion of financial inclusion in their countries. It was crucial to establish the baseline that respondent FSPs were targeting these groups as the study sought to understand how the delivery of such products to these specific groups of people was impacted by COVID-19.

3. Impact of Covid-19 on FSPs’ Delivery Channels

Having established a baseline for FSPs’ target customers and financial services offered before COVID-19, the study then sought to establish the impact of COVID-19 on FSPs with a focus on changes in financial services delivery channels. The survey asked respondents about adaptations made to delivery mechanisms, changes to product offerings, and changes to operations as well as their assessment of risks that may have heightened due to these changes.

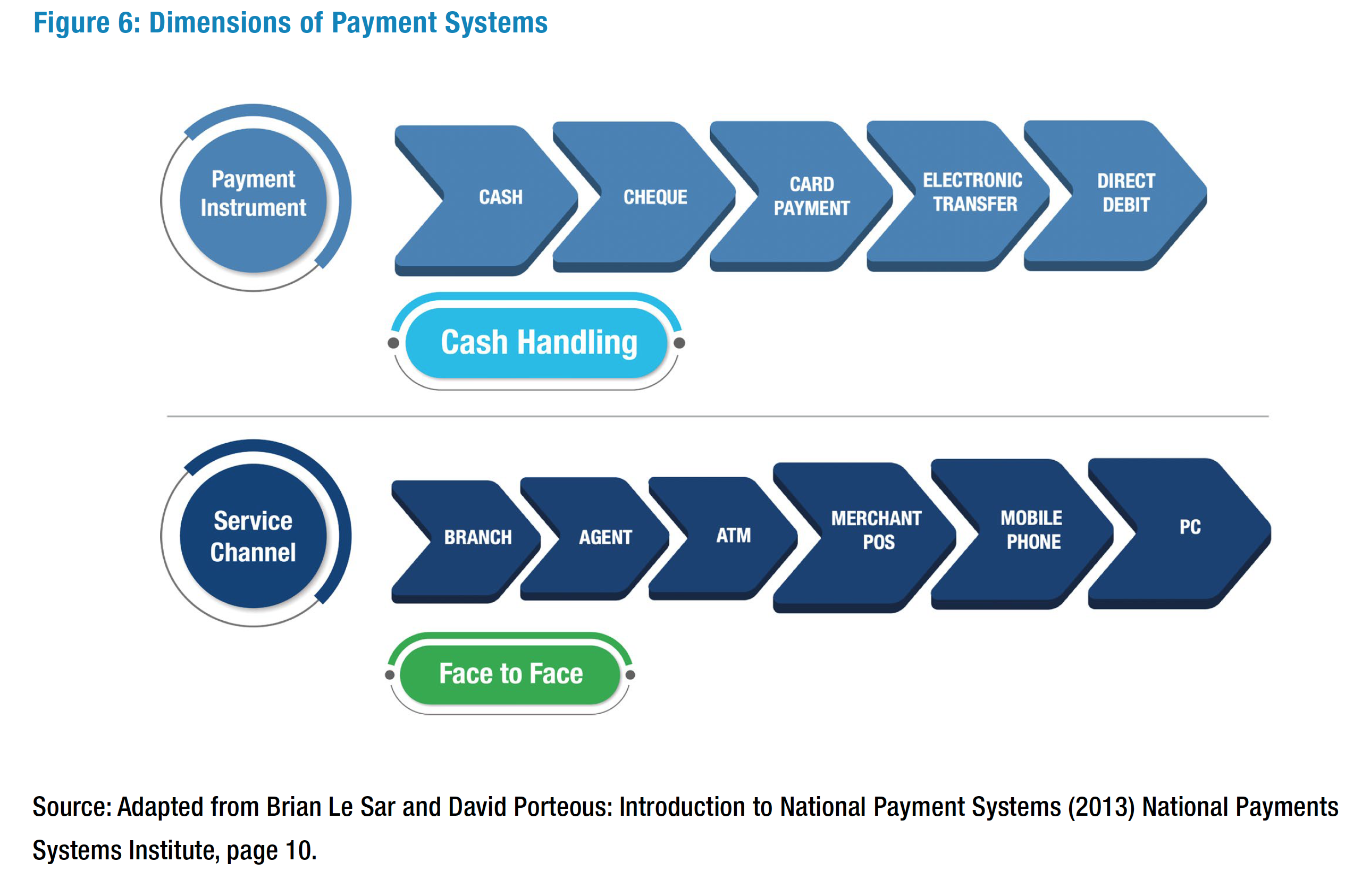

The universe of delivery channels in use pre-COVID included both F2F and non-F2F channels. As Figure 6 below shows, the two major channels that require F2F interaction between the customers and FSPs are bank branches and agents. The rest of the channels, from Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) to personal computers (PCs) (depicting internet based transactions), are deemed non-F2F.

3.1 IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON FSPS’ F2F DELIVERY MODELS

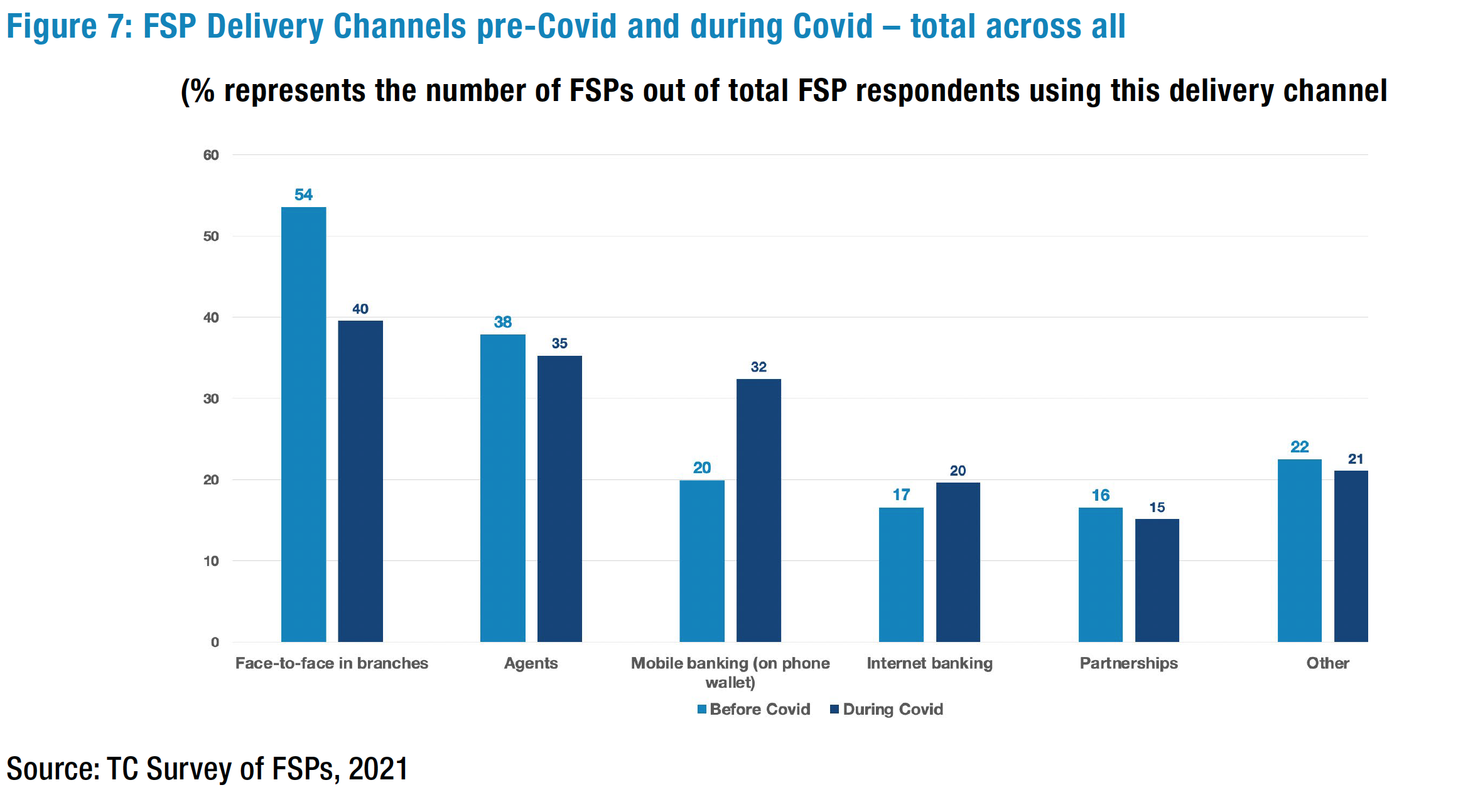

The advent of COVID-19 resulted in FSPs adapting their delivery mechanisms for financial services. Figure 7 below shows that overall, face-to-face delivery in branches during COVID-19 was significantly reduced across the three countries. Before the pandemic, 54% of FSPs in the three countries delivered financial services through F2F contact in branches; this percentage declined significantly to 40% as the pandemic hit the countries. Delivery through agents, which also implies some F2F contact, also declined with 38% of FSPs using this delivery channel before COVID-19, compared to 35% during the pandemic.

This decline in F2F delivery was to be expected as FSPs adapted to doing business in the new environment of social distancing rules that dictated less person-to-person contact. The decline in the use of agents was relatively small. This was because, in all three countries, agents provided an effective mode of delivering F2F services in a localized community. In fact, the use of agents increased in Zambia during COVID-19 as more FSPs sought to utilize local agents instead of bank branches.

In addition, the shift away from F2F delivery was motivated by the desire of customers and FSPs alike to avoid the handling of cash, which was deemed to be one of the carriers of the COVID-19 virus. “When COVID-19 got to Rwanda, we knew that people got contaminated by touching the virus, so cash was seen as a good carrier for that virus, and we thought that people should not be in touch with cash so we had to promote cashless payments,” explained an FSP from Rwanda. The need to avoid in-person contact and to reduce the handling of cash meant that FSPs promoted the use of digital delivery mechanisms, especially mobile banking, during the pandemic (see Figure 7 above), taking advantage of relatively high mobile phone penetration rates across the three countries. Three reports by Datareportal on the use of digital delivery in the three countries show that the mobile connection rates are 73%, 87%, and 88% of the total population in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Zambia respectively [3] In the survey, the proportion of FSPs in the three countries that offered financial services through the mobile phone increased from 20% before COVID-19 to 32% during the pandemic (see Figure 7).

Use of internet banking also increased, albeit marginally from 17% to 20% (see Figure 7). Internet banking requiring logins via applications or FSP websites would not ordinarily be a channel appropriate for financially excluded groups as access to smartphones and or internet is still limited in all three countries.

| In response to COVID-19 restrictions, FSPs introduced innovative ways of reaching their customers through social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Short Message Service (SMS), and Facebook. Over one third of FSP respondents reported using these social media platforms to reach out to their clients. |  |

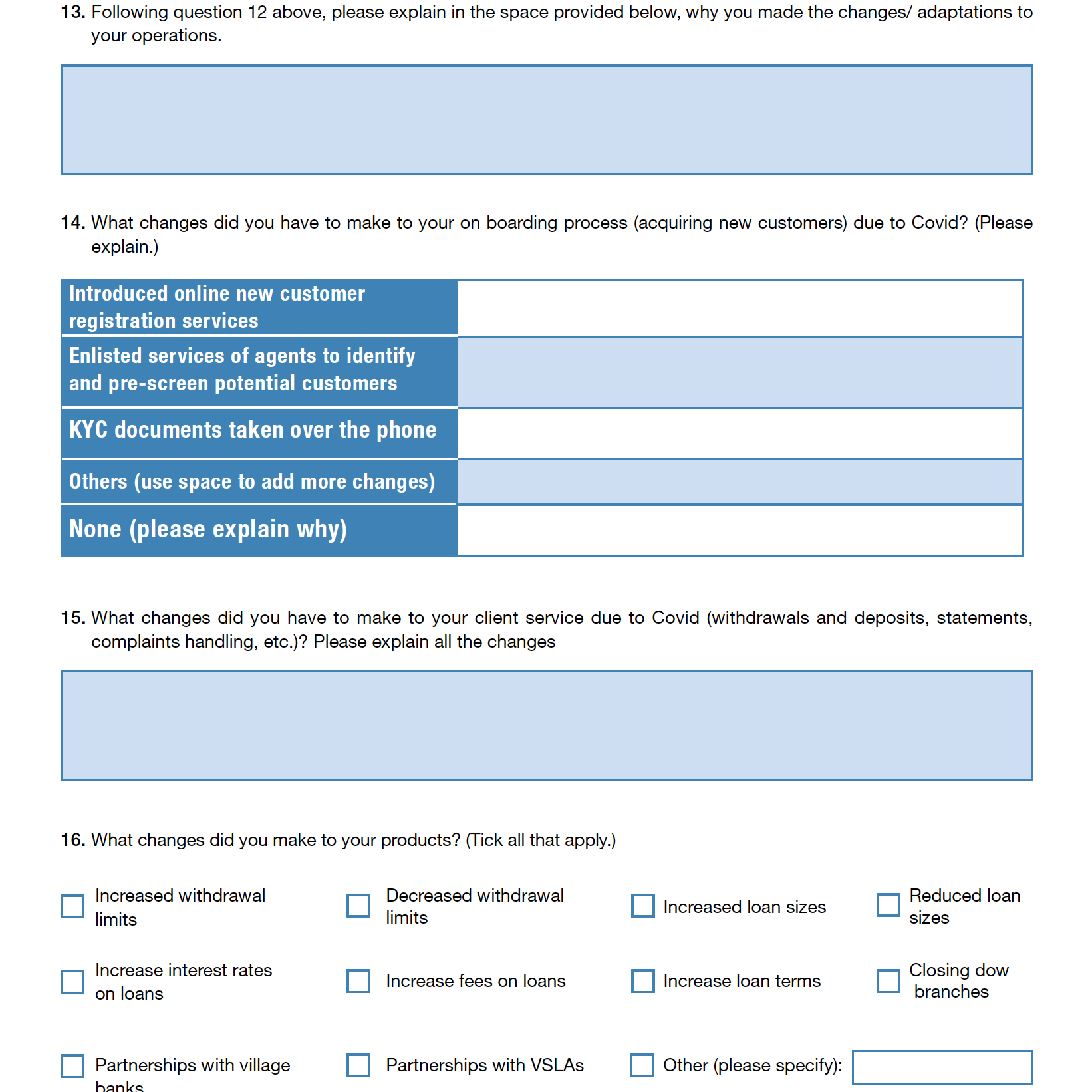

FSPs introduced these delivery channels to bridge the service delivery gaps created by lockdowns which limited clients’ access to branches. The idea was to bring convenience through self-service facilities, enabling clients to access their accounts without travelling to the branches, and to create alternative ways through which clients could pay back their loans. FSPs also wanted to protect their clients against COVID-19 and avoid the circulation of physical cash which could be a vector for spreading the virus. They aimed to facilitate instant communication with their customers, enable their customers to use phones to scan national IDs/passports and other important documents for submission to the FSPs. Introducing or heightening the use of these channels would ensure business continuity amidst the pandemic even though it may have increased FSPs’ risk exposure, as detailed later.

In a bid to reach their customer base during COVID-19, FSPs partnered with technology firms and telecommunication companies (telcos) for micro credit and bank-to-mobile transfers [4] and to enable push/pull [5] capabilities, and with FinTech companies to build digital delivery channels. Some FSPs signed partnerships with telcos, microfinance institutions (MFIs), savings and credit cooperative societies (SACCOs), agricultural cooperatives and other microlending institutions in order to continue to serve their customers during COVID-19. For example, in Rwanda where SACCOs are very active (see Annex 3), consumer associations echoed that some commercial banks or MFIs partnered with these SACCOs in order to avail services to their rural customers who would not be able to travel to bank branches during lockdowns. SACCOs typically operate in the community, with branches located in close proximity to the membership.

While the shift to digital service delivery was not caused by COVID-19, the study found that the challenges created by the pandemic had a catalytic effect on accelerating this shift. Across all three countries, FSPs came to realize that digitalization was inevitable and fast-tracked plans for the use of digital delivery. In some cases, as reported by study respondents, the digital channels were already available but uptake was slow until COVID-19 made it an imperative.

The speed and ease with which FSPs in the three countries transitioned from F2F to non-F2F – primarily digital delivery of financial services – depended on the digital adoption rates in the countries pre-COVID and government policies to promote digital delivery. This is explored in the next section.

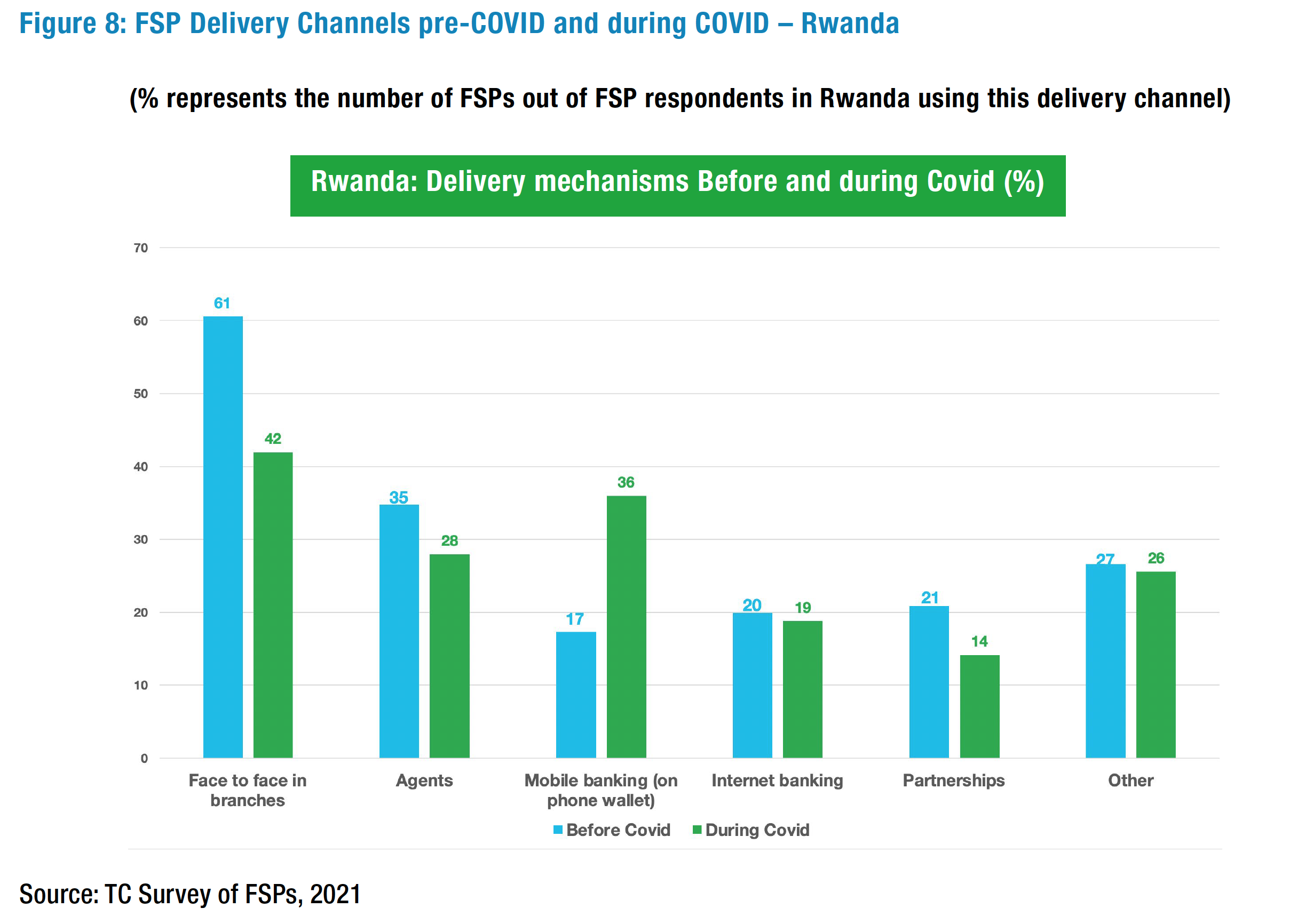

3.1.1 COUNTRY EXPERIENCES: RWANDA

In the case of Rwanda, where respondent FSPs cited a significant increase in use of mobile banking from 17% to 36% (see Figure 8 below), policy changes also contributed to the increased uptake. Before COVID-19, a World Bank report [6] estimated 3G and 4G coverage to be about 93.5% and 96.6%, respectively. However, according to Africa’s Pulse (2020), the uptake of 4G was very low – with only 8.5% of Rwandans using 4G, mostly due to low access to smart phones. Rwanda Consumer’s Rights Protection Organization (ADECOR) reported during the study that even with such high connectivity, internet fluctuations were still experienced both in urban and in rural areas.

Once the pandemic started, the Rwandan government, as part of its national effort towards a “cashless” society, worked with mobile network operators to offer a “90-day zero charge” on mobile transactions; for example, bank-to-wallet transfers or payment to merchants (P2M) (see Box 1). Respondents to the survey in Rwanda cited a greater than 100% increase in mobile phone usage during this period. The change in digital uptake was well documented by Carboni and Betser (2020) [7]. They indicated that the value of P2P transfers between February and March 2020 was on average 7 billion RWF per week, but increased to 40.3 billion RWF per week in April 2020 when the zero charges window was introduced.

BOX 1: PROMOTING A “CASHLESS” SOCIETY IN RWANDA DURING COVID-19

3.1.2 COUNTRY EXPERIENCES: ZAMBIA

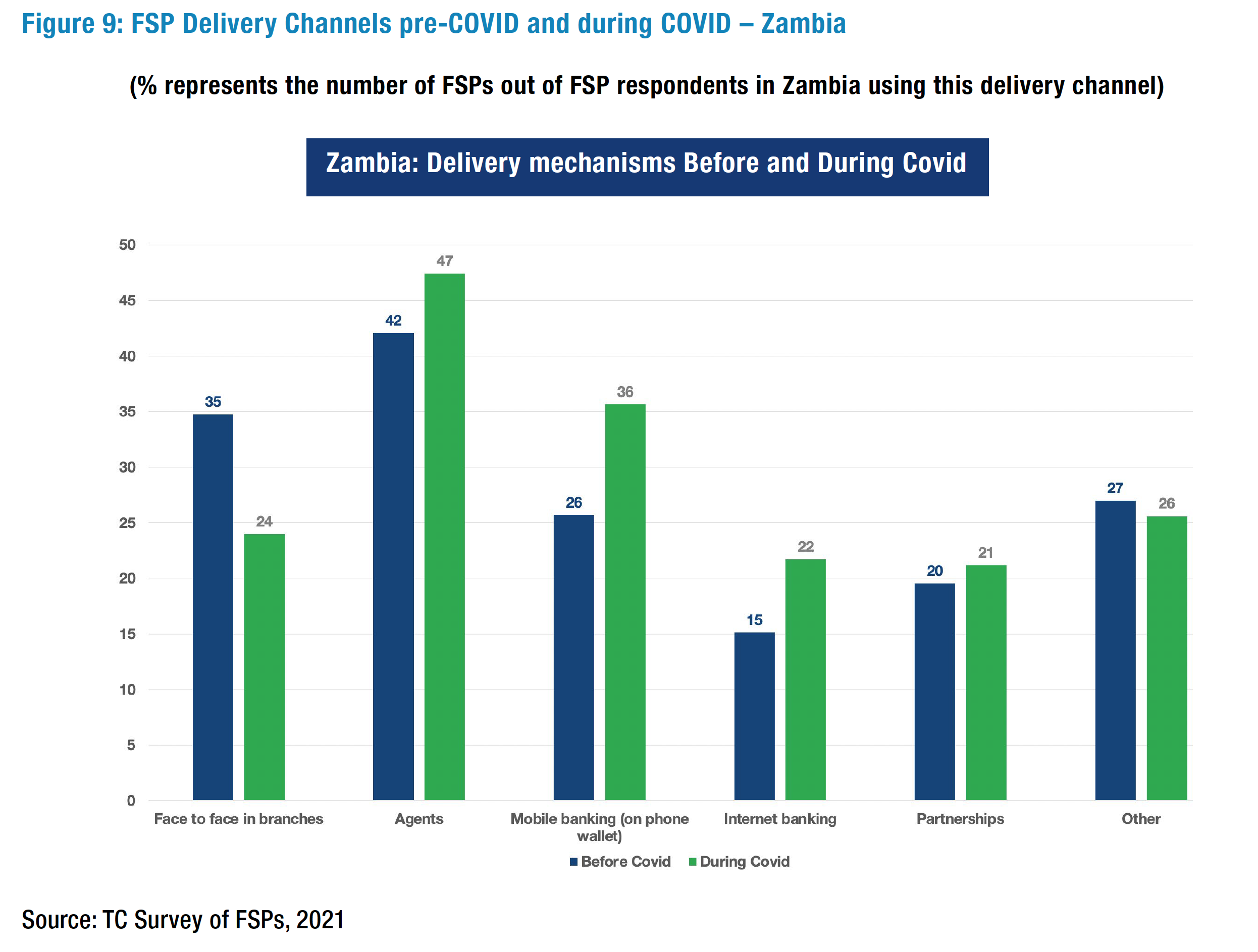

While F2F delivery by FSPs in Zambia significantly declined from 35% to 24% (see Figure 9), in contrast to the other two countries where the use of agents slightly decreased, the use of agents by FSPs increased from 42% to 47%. This should not be surprising as ‘cash in – cash out’ agents often increase as mobile money transactions increase.[8] Even before COVID-19, FSPs’ use of agents in Zambia was higher than their use of F2F delivery in bank branches or mobile banking. This continued to prevail during the pandemic. Even though agents also have F2F contact with their customers, the FSPs regarded this as “limited F2F” as the contact occured in local communities and in open spaces with lots of ventilation, making it possible to comply with social distancing rules during COVID-19. For example, when there were travel restrictions or limitations on crowds in banking halls, agents could still serve their local communities where they are located. Zambia enforced a partial lockdown in March 2020 with essential service facilities like banks remained open. This meant that people could still travel and transact in the banking halls as they did not need a pass for essential travel. Government efforts to promote the use of agents during COVID-19 contributed to the significant increase in their use (see Box 2).

BOX 2: USING AGENTS TO OFFER “LIMITED F2F” DELIVERY OF FINANCIAL SERVICES

3.1.3 COUNTRY EXPERIENCES: SIERRA LEONE

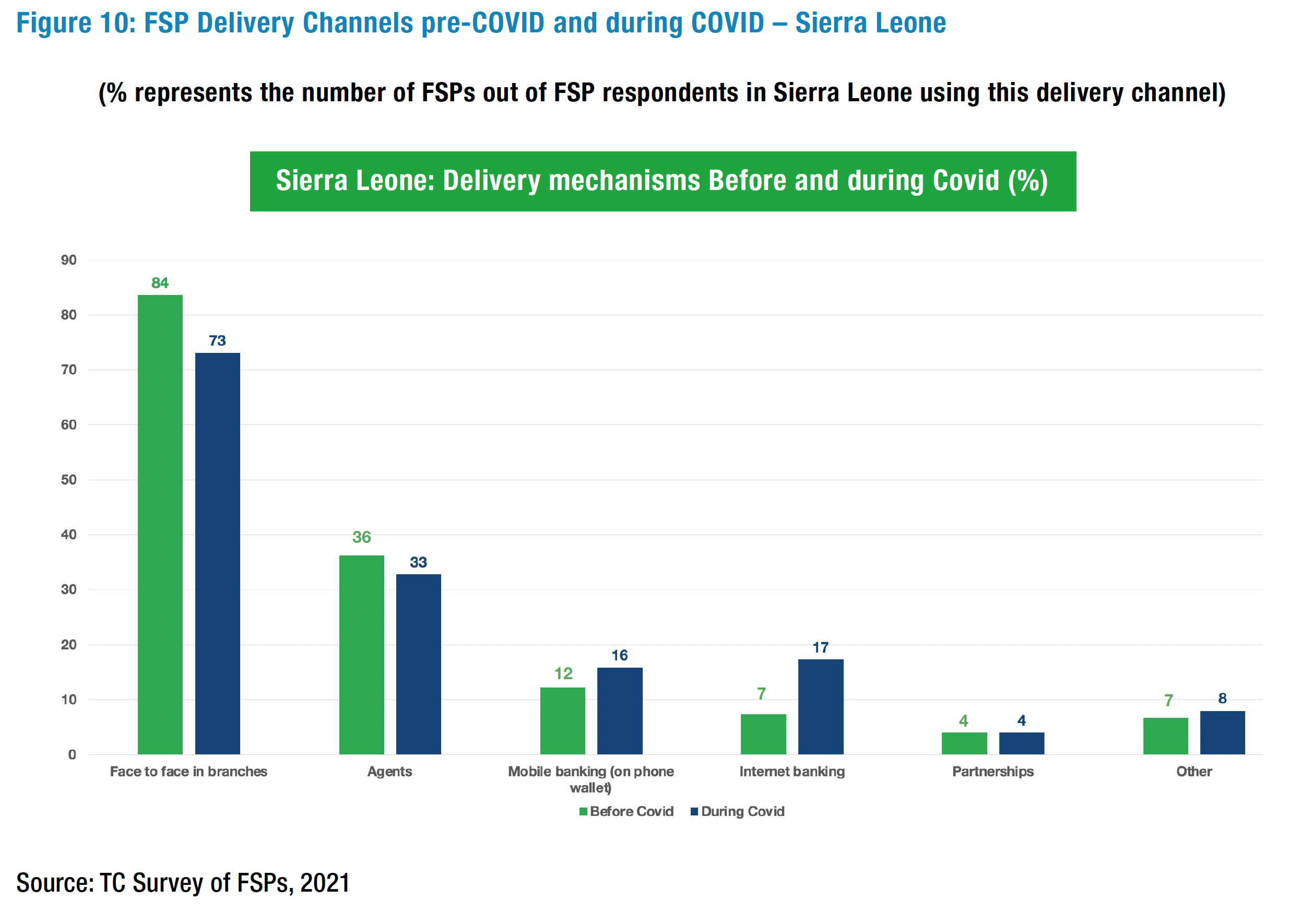

While F2F delivery was reduced in all three countries, the reduction was least apparent in Sierra Leone (see Figure 10). Box 3 below describes some adaptations to group lending in Sierra Leone that made it possible to continue with F2F delivery of financial services. Respondents offered a few reasons for the continuation in F2F delivery compared to Rwanda and Zambia. First, some survey respondents described the commercial banks and microfinance institutions as risk averse and not as quick to introduce mobile banking. In 2019, only 30% [13] of the adult population had access to digital financial services.

Second, the regulatory environment prior to 2020 did not allow commercial banks and other FSPs to use USSD codes [14] for banking services. Only MNOs were allowed to use USSD codes, thus creating an uneven playing field. This changed with the advent of new regulations, and banks started using USSD code and creating products that could be delivered digitally.

Third, Sierra Leone seemed to have not suffered as much from COVID-19 up to 2021. According to the World Health Organization,[15] from January 2020 when the first case was reported to May 4, 2021, the West African country had 4,062 cases and 79 deaths, which were lower than those in Rwanda and Zambia. The experience that health authorities in Sierra Leone gained from the Ebola outbreak in 2013-2016 helped them to prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic even when little information was available. For example, Sierra Leone had previously introduced the “less touching” policy as Ebola was a “highly infectious, transmittable and communicable” disease (Kangbai, 2020). The same author noted that “one of the most relevant experiences Sierra Leone obtained from the Ebola outbreak which is now being used to prevent the outbreak of COVID-19 in the country is the targeted quarantining of all categories of COVID-19 patients”. Thus the authorities were better able to quickly implement the COVID-19 health protocols, which were similar to protocols adopted for Ebola. FSPs continued to offer F2F services observing these COVID-19 protocols.

In order to further promote the shift to digital service delivery, the Bank of Sierra Leone, working with development partners, has embarked on a number of initiatives to motivate innovation among FSPs including introducing a tiered KYC policy framework in June 2020. [16] This allowed simpler KYC requirements for customers who are assessed to pose lower risk. FSPs in Sierra Leone have also embarked on financial literacy campaigns using short videos, radio, and field ambassadors in order to fill in the knowledge gaps of customers that has so far hindered the uptake of digital financial services.

BOX 3: ADAPTATIONS TO GROUP LENDING DURING COVID-19

3.2 FSP CHANGES TO OPERATIONAL MODELS TO SUPPORT NON-F2F DELIVERY

To support the switch from F2F to non-F2F delivery models, FSPs in all three countries indicated they had to change several key operational processes, such as customer onboarding and ongoing client services. These changes are highlighted below, with the implications of these changes for supervisory risks explored later.

3.2.1 CHANGES TO CUSTOMER ONBOARDING AND KNOW-YOUR-CUSTOMER (KYC) PROCESSES DUE TO COVID-19

| Survey results show that respondent FSPs switched from ‘manual’ customer applications for account opening (‘onboarding’) – where customers met with FSP staff and filled out physical forms – to online processes, where clients could apply over the phone, through WhatsApp for Business or through the FSP website. A major shift for most FSPs was in the way KYC documents were submitted to the FSPs, with documents via Whatsapp or email accepted as clients could not come into the banking halls. Practices such as scanning and emailing KYC documents, with originals being sent via courier services using and e-signatures, became more acceptable. However, for control purposes, online submissions were required to be confirmed in person, especially for new customers. Even for insurance purposes, FSPs offering insurance services also engaged in use of SMS and online platforms for new clients’ onboarding or for renewal of insurance. |  |

Survey results show that respondent FSPs switched from ‘manual’ customer applications for account opening (‘onboarding’) – where customers met with FSP staff and filled out physical forms – to online processes, where clients could apply over the phone, through WhatsApp for Business or through the FSP website. A major shift for most FSPs was in the way KYC documents were submitted to the FSPs, with documents via Whatsapp or email accepted as clients could not come into the banking halls. Practices such as scanning and emailing KYC documents, with originals being sent via courier services using and e-signatures, became more acceptable. However, for control purposes, online submissions were required to be confirmed in person, especially for new customers. Even for insurance purposes, FSPs offering insurance services also engaged in use of SMS and online platforms for new clients’ onboarding or for renewal of insurance.

Other FSPs enlisted the services of agents to identify and pre-screen potential customers. These agents were registered, trained and incentivized to register and on-board customers as well as collect loan repayments. Mobile bankers were also trained and assisted with screening potential clients.

For group clients, field officers engaged group leaders to assist with some elements of know-your-customer verification instead of the FSP staff meeting physically with all group members. Clients were also trained online on how to use the digital platforms, set up by FSPs, to encourage usage of the online platforms for the submission of online applications.

In some cases, FSPs simplified onboarding requirements for ‘less risky’ customers, usually those seeking small loans, with the onboarding done telephonically. In Zambia, KYC requirements for such borrowers were simplified to producing a copy of identification and a letter of request. In such cases, the credit evaluation would be done digitally based on credit algorithms. Countries like Kenya had long introduced digital loans, well before COVID-19, but in the three countries such loans were not as widespread before COVID-19.

3.2.2 FSP CHANGES TO CLIENT SERVICES DUE TO COVID-19

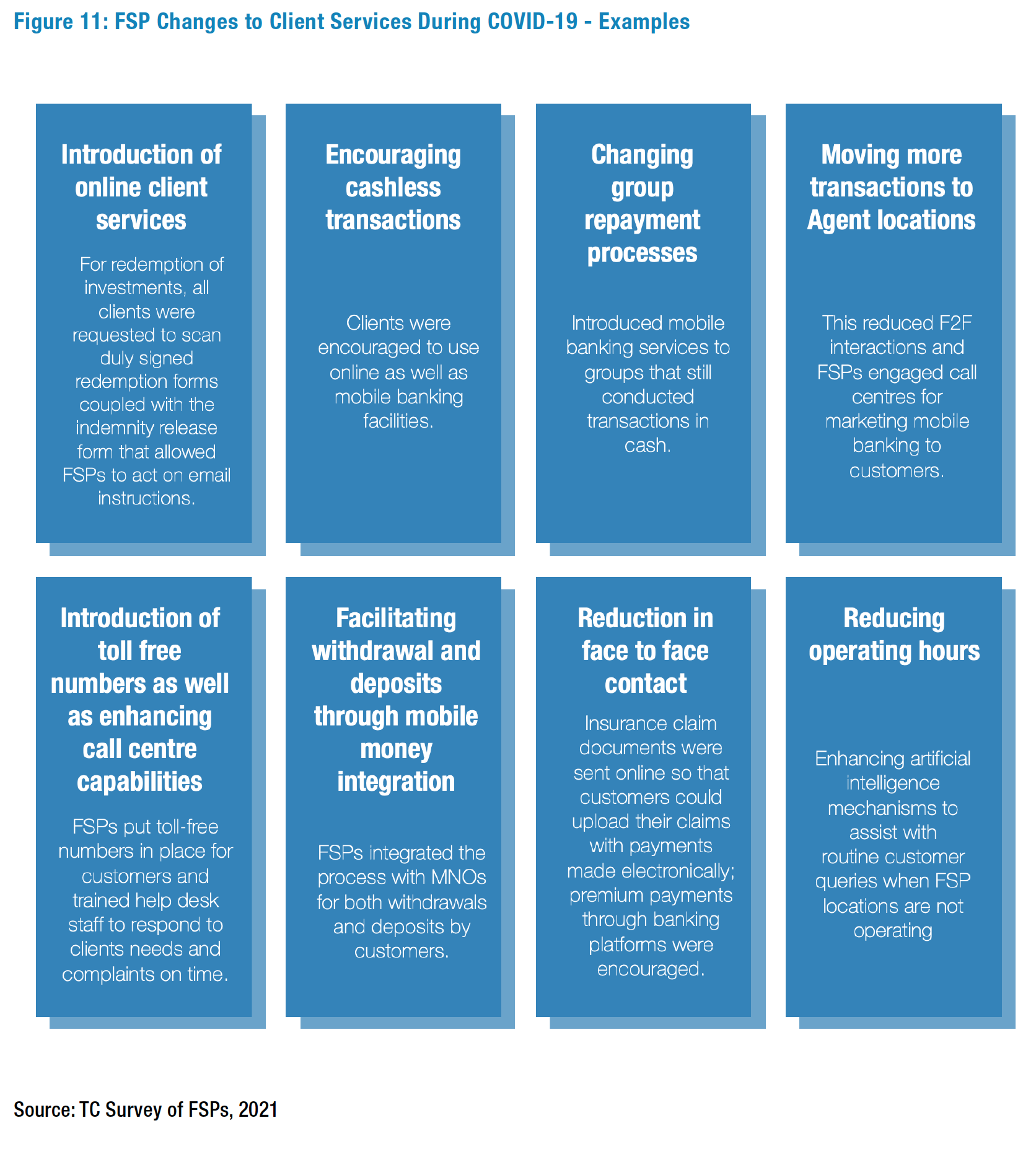

In a bid to continue to serve clients remotely, respondent FSPs indicated that they made several client services changes due to COVID-19. These included introducing virtual client services, encouraging cashless transactions, moving more transactions to agent locations, introducing toll-free service numbers as well as enhancing call centre capabilities, facilitating withdrawal and deposits through mobile money integration, and reducing F2F contact and operating hours. Figure 11 below summarizes the main changes in client services.

3.2.3 FSP OPERATIONAL ADAPTATIONS TO SUPPORT CHANGES IN DELIVERY CHANNELS AND CLIENT SERVICES

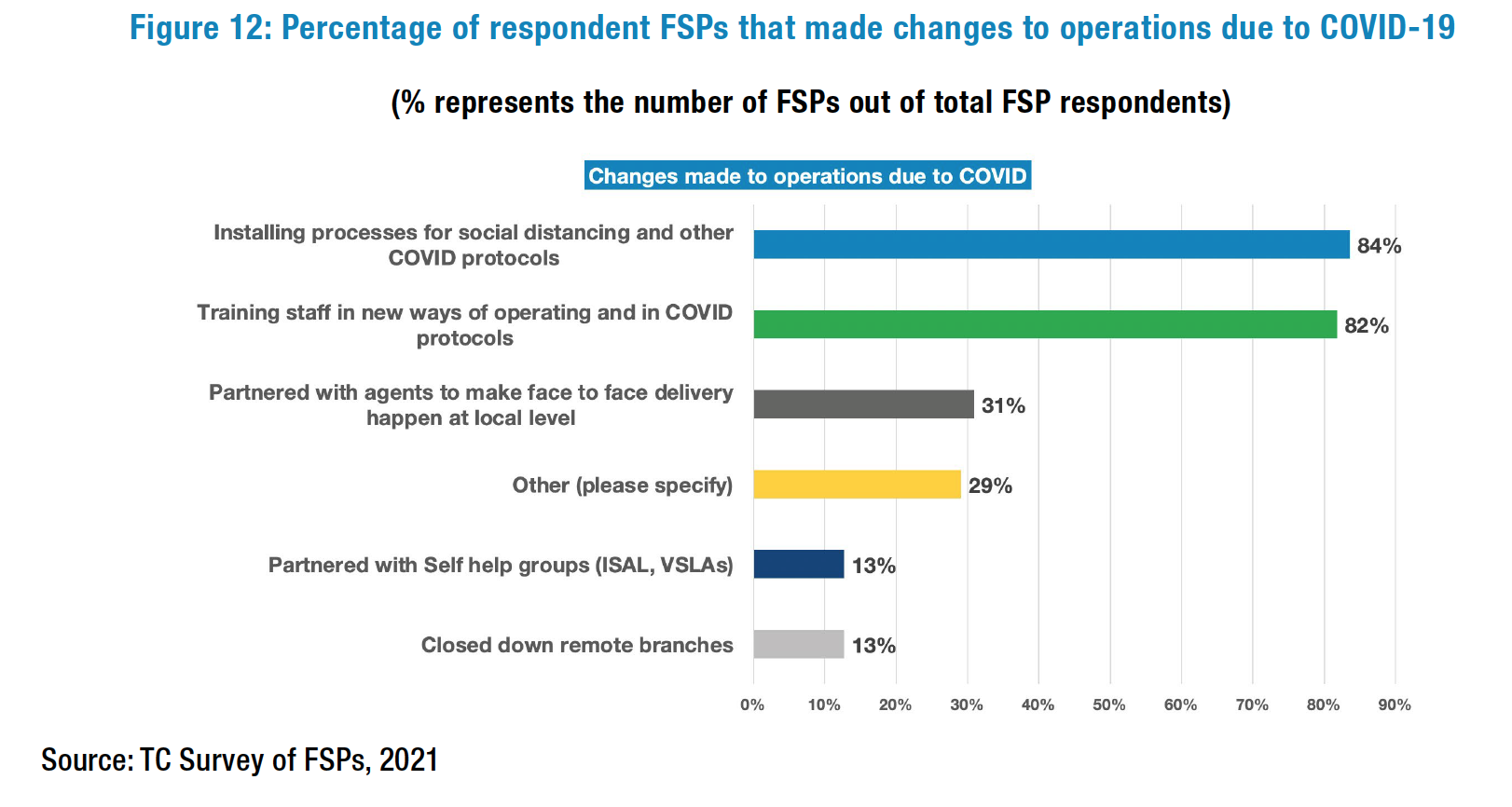

FSPs also made other general changes to their operations to support the shift to non-F2F delivery. Figure 12 shows the main changes/adaptations made by FSPs to their operations due to COVID-19. FSPs highlighted several reasons for making the operational changes. Besides the need to comply with COVID-19 regulations, these reasons included:

Enhance access to their financial services without clients necessarily having to come to the bank;

Protect both staff and customers;

Ensure business continuity;

Decongest the banking halls and ensure customers were able to perform transactions without necessarily leaving their homes or visiting the bank branches.

Two major changes cited by 33% of FSP respondents included redesigning banking halls to comply with COVID-19 social distancing requirements, and ensuring that staff were trained in COVID-19 protocols (Figure 12). These two changes were in direct response to COVID-19 health regulations.

Other changes included partnering with Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs) and using agents to reach and serve clients in underserved communities. In all three countries, there were examples of FSPs and Mobile Network Operators working together to ensure the bank-to-wallet (push-and-pull) functions worked for customers wishing to access their funds through their phones.

In addition, FSP respondents noted the internal organization issues around working from home and ensuring that staff could continue to serve customers remotely. FSPs adopted the use of remote collaboration workspaces such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, and other platforms to hold meetings with staff and management who were working from home.

3.3 CHANGES MADE TO FSP PRODUCTS DUE TO COVID-19

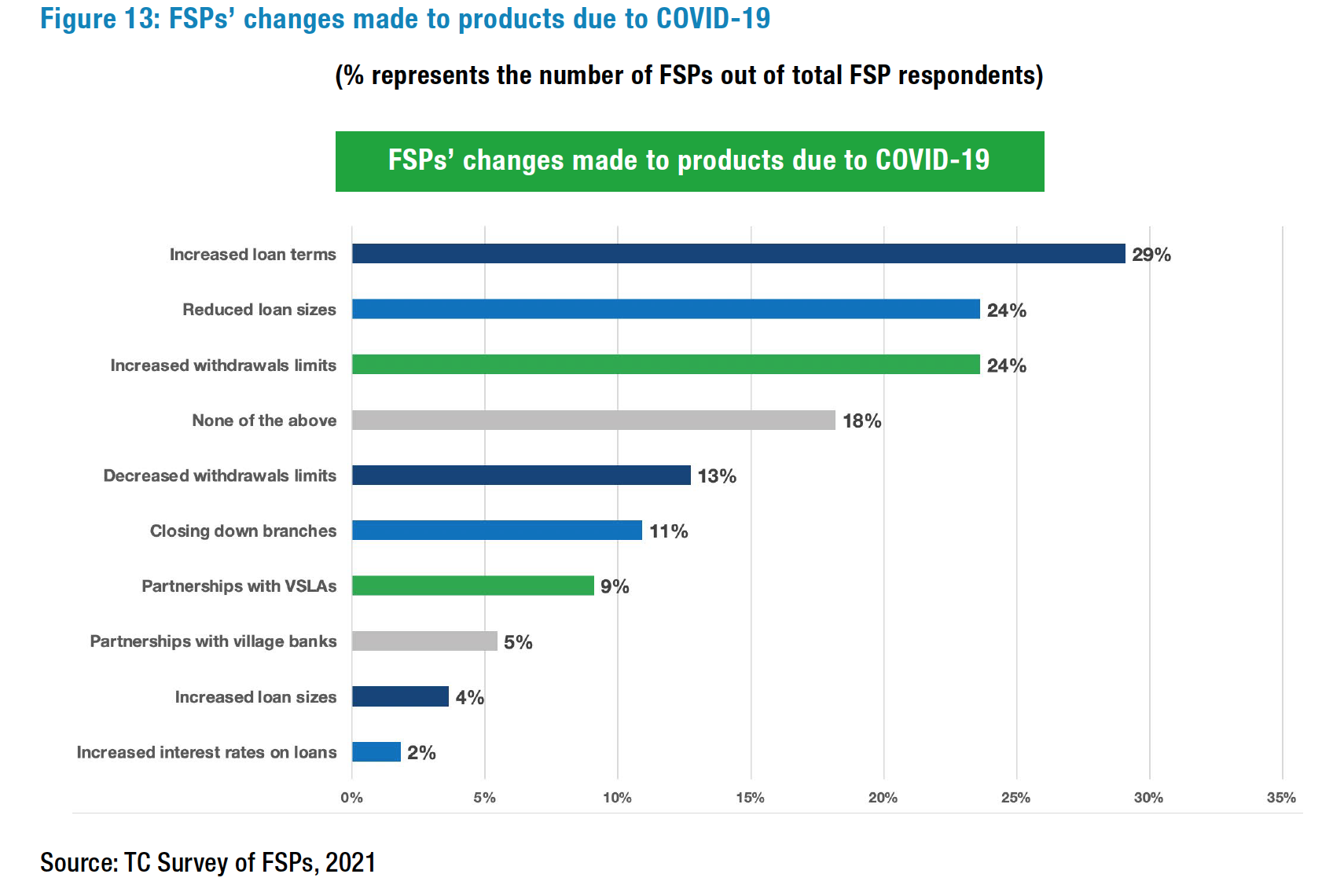

FSPs also made changes to their financial products and to their product terms in response to COVID-19 challenges (see Figure 13). Three main changes were:

- Increasing loan terms (29% of all FSPs surveyed);

- Reducing loan sizes (24% of FSPs); and

- Increasing withdrawal limits for customers (24% of FSPs).

Given that lockdowns curtailed their clients’ ability to continue with their economic activities, it made business sense for FSPs to increase loan terms to allow their clients more time to repay their loans while still maintaining client relationships. Reducing loan sizes for new loans helped FSPs to minimize their credit exposure and manage liquidity issues in the COVID-19 operating environment.

To minimize the frequency of client trips to FSP facilities for cash withdrawal purposes, 24% of FSPs surveyed increased cash withdrawal limits for their clients. An exception to this was Rwanda, where cash withdrawal limits were reduced to encourage clients to shift to electronic payment mechanisms. One respondent noted that the ATMs in Rwanda were dispensing less cash than usual in order to encourage use of electronic payments.

A few FSPs (9%) partnered with VSLAs and village banks to serve existing customers in remote rural areas. 11% of respondents cited branch closures as a key strategy employed to reduce costs during COVID-19. However, not many FSPs took that route as such a move would be detrimental for their business and for financial inclusion in rural areas. For example, in cases where rural branches were meant to serve the rural population and smallholder farmers, closing down a branch would most likely make access difficult for those segments. In Zambia, the financial supervisors noted that rural branch closures did not necessarily reduce the financial access of the rural population as FSPs would have created alternative delivery channels such as mobile banking or banking through agents.

Other changes made to products include introducing new loan products, such as loans to schools and teachers with a grace period for repayment up to when the schools reopen, and new agricultural loans targeted at financially excluded groups. The agricultural sector was deemed an essential service that was not as affected by lockdowns. Other measures cited by FSPs include waiving penalty fees, allowing flexibility for clients to redeem part or all of their investments at will, introducing refinancing and loan rescheduling options, and offering moratoriums for all loans. Secondary research also suggests that loan rescheduling heightened significantly during COVID-19, supported mostly by government directives where rescue packages included either repayment moratoriums or refinancing mechanisms.

3.4 SUMMARY: FSP CHANGES TO DELIVERY CHANNELS DURING COVID-19

FSPs across the three countries adapted their financial services delivery channels in response to COVID-19 to different extents.

Those FSPs that moved from F2F to non-F2F channels to comply with social distancing rules moved mainly to mobile banking. The speed and ease with which FSPs could switch to non-F2F delivery channels depended on various factors, such as the physical infrastructure to support the switch to digital delivery of financial services, the policy environment, and the financial and digital literacy levels of the general populace.

The next chapter looks into the implications of these changes on financially excluded groups.

4. Financially excluded customer groups: Impact of COVID-19 and FSPs’ shift to non-F2F delivery

The changes in delivery channels made by FSPs in their responses to COVID-19 were ideally meant to ensure that they would continue to serve their target customers, including the financially excluded or vulnerable customer groups. Non-F2F, primarily digital delivery, is supposed to be a fundamental enabler of financial inclusion and has been hailed as accelerating digital financial inclusion as FSPs would be able to reach customers even in remote rural areas (FAO, 2021). However, current literature points to key risks or downsides of digital delivery with regards to financial inclusion, which is corroborated in the survey results.

First, there are significant concerns about digital delivery widening the financial inclusion gap between those with and without access to the technological tools needed for digital access. Vulnerable populations, including rural customers, smallholder farmers, women, the elderly, and the very poor may not have access to the simple-feature phones that are needed to access digital wallets using USSD codes, which is the most basic requirement for mobile banking. According to a GSMA 2020 [17] study, women are 20% less likely to use the internet on a mobile phone than men. Another GSMA report in 2015 [18] indicated that 200 million fewer women than men in developing countries have access to mobile phones.

Furthermore, there are concerns around data privacy, transparency, and predatory lending (FAO, 2021) that may hinder the uptake of financial services delivered digitally, especially by vulnerable groups. ADECOR noted that even when the government had reduced fees for certain digital financial services to zero for three months, most rural households still did not trust the digital concept and uptake was much slower than in urban areas.

The study sought to understand how the different financially excluded customer groups were affected by the shift to non- F2F digital delivery by FSPs. As comprehensive data is lacking, the nature of the evidence here is anecdotal, and is based on FSPs’ and consumer associations’ interactions with these vulnerable groups and their perceptions of the challenges faced by these groups. FSPs highlighted several drivers of the impact on these vulnerable groups, some of which were corroborated by consumer associations and by the financial supervisors during discussions with the TC research team.

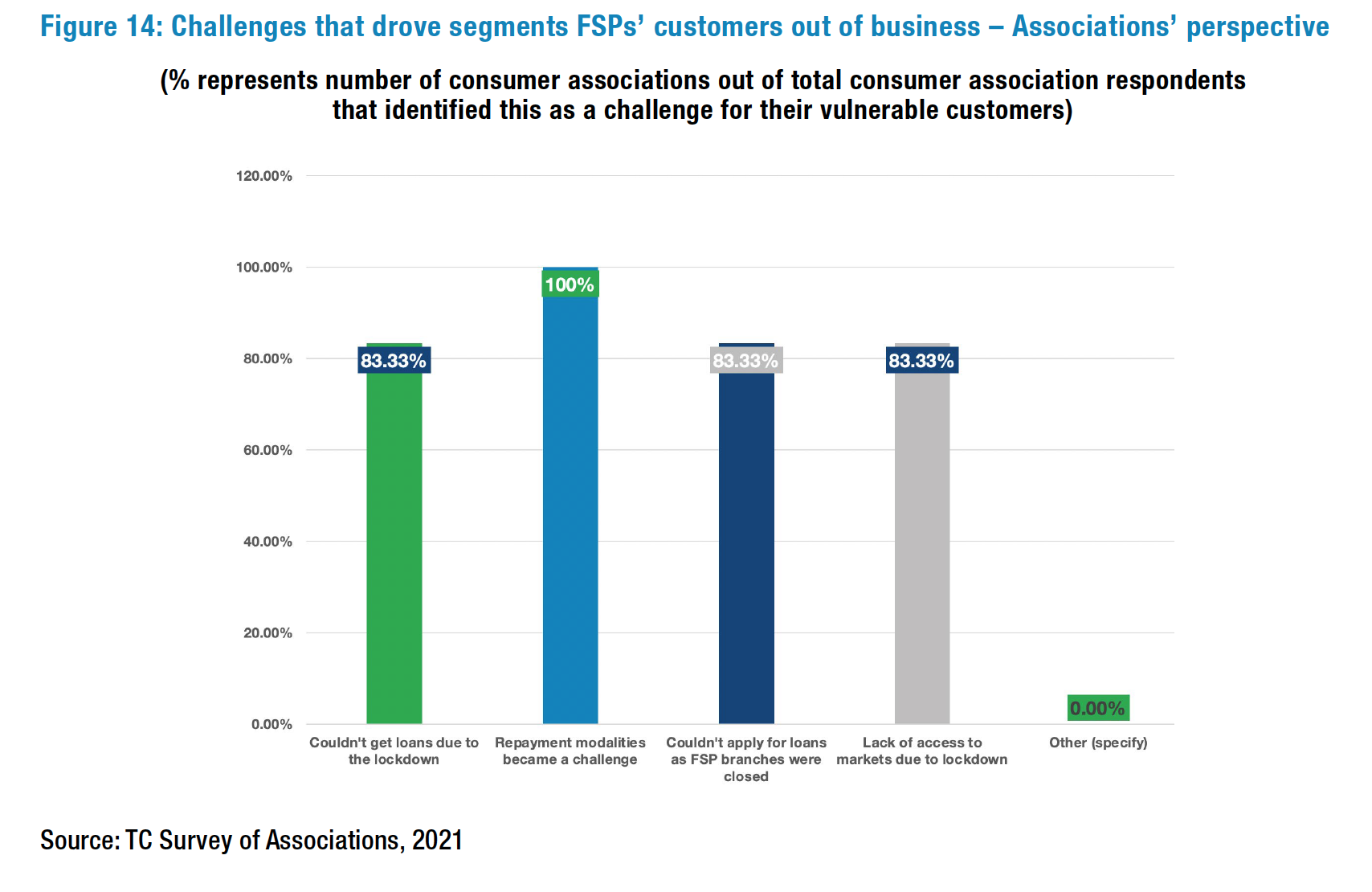

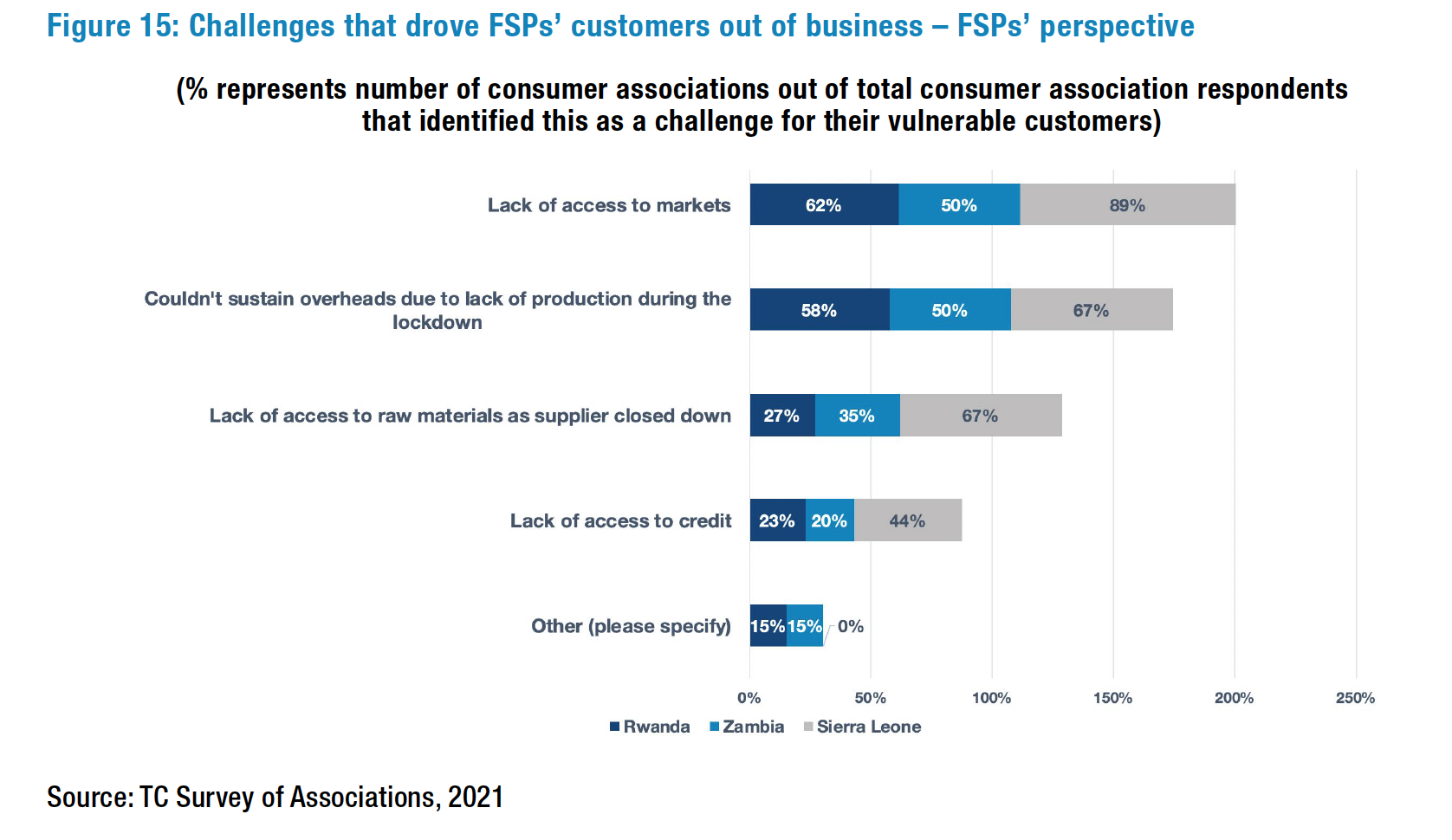

Consumer associations reported that the greatest impact of Covid-19 from a financial inclusion perspective was the lack of access to repayment modalities by vulnerable groups, which in turn affected their access to future credit and FSPs’ willingness to lend to these groups. This perception was shared across the three countries but differed in how the associations and the FSPs perceived the impact on their vulnerable customer groups (see Figures 14 and 15 below).

FSPs believed that the greatest impact on client segments was the lack of access to markets which in turn affected their sale revenues. However, consumer associations, focusing mostly on clients that had borrowed, felt that the greatest challenge was access to alternative repayment channels. It took a bit of time for FSPs that were not already linked to mobile phone payments to get connected and to advise clients on how to repay.

4.1 IMPACT ON WOMEN

“How can I use my phone to

withdraw my money at the bank?”

asked one lady in Rwanda.

Women, the majority of whom are active in the informal sector that suffered the most due to COVID-19 lockdowns, were severely impacted economically. Even in Zambia, where there was a partial lockdown, women entrepreneurs recorded reduced incomes due to the depressed demand for their goods and services, except for those providing essential services. Many lost their jobs while others closed their small businesses, all of which negatively impacted their livelihoods. One respondent noted that the closure of local markets meant that many women who ran small businesses in these markets lost their incomes. Women who were cross-border traders in the three countries were affected by travel restrictions to countries such as China, South Africa, and Turkey. Most of these women could not adapt to the new technology-driven environment for making business transactions through e-commerce; for example by placing orders online and making electronic payments to offshore suppliers. Even though some digitally-literate women managed to adapt to digital forms of transacting, many did not trust these platforms. For example, in Rwanda one respondent cited lack of trust among women about digital transactions, which meant that the push towards a cashless economy had not yet gained much traction, particularly among low-income groups of women.

In all three countries, poor connectivity in urban areas but more so in rural areas compounded the challenges of digital financial service delivery. Cashless transactions were fraught with challenges; for example, funds erroneously reflected in the system as having been transferred but not going through. Such incidents made women more hesitant to rely on digital banking. In Rwanda and Zambia, women were reported to prefer and to be more reliant on SACCOs and informal savings groups instead of digital delivery for financial services. In Zambia, clients also complained about the high cost of digital transactions.

To address the lack of familiarity and trust with digital transactions, consumer associations are working together with the regulatory authorities and associations to raise digital awareness. In Rwanda, the consumer associations have embarked on television and radio talk show awareness campaigns to promote the digital and cashless economy. Indeed, these campaigns in Rwanda may have borne results as described by Carboni and Bester (2020) [19] , which showed that women users or subscribers to person-to- person (P2P) services between early March and mid-April 2020 had increased from 151,000 to 610,000 subscribers. The increase is notable, although it is still less than the increase in male users where subscribers increased from 355,000 to 1,083,000.

One caveat is that without accurate data on the use of mobile phones within households, it may be difficult to know who actually uses or drives the digital transactions since mobile phones in families tended to be used by more than one person. One survey respondent noted that a woman might not own a mobile phone or might not be digitally literate and therefore ask her husband to transact on her behalf. In financial surveys, such transactions will be tagged to the (male) owner of the phone when in actual fact the transactions had been driven by the women in the families, thus under-reporting women’s use of digital financial services.

Besides digital literacy, the traditional barriers for women accessing financial services still exist, including lack of appropriate identification for fulfilling KYC requirements, low access to phones, and high cost of P2P transactions on typically smaller amounts handled by women entrepreneurs. [20] These barriers should be addressed if women are to benefit from FSPs’ shift to digital service delivery due to COVID-19. Financial supervisors can play a pivotal role in addressing these barriers. For example, the Bank of Sierra Leone is working with KIVA to launch an identification linked to the credit reference bureau.

4.2 IMPACT ON YOUTHS

Youth unemployment was already high in the three countries pre-COVID. COVID-19 aggravated the situation, thereby making access to financial services even more difficult for this vulnerable group. Job losses among youths compounded the challenge as companies either downsized or closed operations, including some youth-owned businesses. FSPs in Rwanda expressed the view that most youth businesses in Rwanda are in hospitality, transport, and recreation sectors, and these sectors were severely impacted by lockdowns.

Being the more tech-savvy category among vulnerable groups, youths’ usage of other digital services or content increased during COVID-19. However, their use of digital platforms did not translate into the use of financial services. Survey respondents noted that the value of funds that moved on the platforms used by youths was very limited.

4.3 IMPACT ON SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (SMES)

SMEs, particularly those in sectors that were locked down, were severely impacted by COVID-19. Many SMEs reacted by closing operations and laying off staff, leaving the barest minimum headcount onboard. One SME said “we are heavily impacted due to long lockdowns. Without producing, [we are] not able to repay existing loans and when back to the market, [there is] no sufficient money to continue operating as usual”. The need for loans generally declined due to reduction in demand of goods and services during lockdowns. Production was also halted due to the lack of inputs. Halting trading during lockdowns severely handicapped the SMEs’ capacity to repay their loans, which in turn now affects their ability to access additional business loans to revive their businesses. Besides credit, the demand for insurance products by SMEs also reduced as insurance was viewed as an unnecessary expense during the downturn.

Most SMEs were not positioned to attract new customers through an online presence, and as such were hard-hit by the COVID-19 lockdowns. The shift to digital commerce was slow or non-existent mostly due to SMEs’ unfamiliarity with online commerce platforms and the high cost of setting up a presence on these platforms. The SMEs that were involved in cross border trading activities had to shut down, especially when physical travel to import goods ceased. In a few cases, FSPs provided mentoring and coaching services to some SMEs to enable them to shift into profitable segments or adopt online shopping.

4.4 IMPACT ON THE RURAL POPULACE AND SMALLHOLDER FARMERS (SHFS)

During COVID-19, access to financial services became even more difficult for the rural populace as the few financial services providers that had some presence in rural areas either closed their branches or could not service them due to travel restrictions during the lockdowns. However, in terms of livelihoods, FSPs noted that rural areas were not as affected as urban areas since their main economic activities were in the agriculture sector that was not as affected by COVID-19 restrictions. The rural customers’ main challenge was limited access to markets for their farm produce, which could not reach their regular urban markets due to travel restrictions. In addition, some rural businesses could not restock as value chains were disrupted, affecting access to inputs by farmers. Due to poor internet access and physical infrastructure for mobile networks in rural areas, the rural customers were unable to access mainstream digital financial services.

Overall, the usage of digital transactions platforms increased more in urban areas than in rural areas where mostly the educated and literate are using these platforms, with the majority of rural populations still transacting in cash. In Sierra Leone, where the shift to digital delivery of financial services was not as pronounced, most FSPs continued to offer F2F financial services in rural areas for borrower groups amidst COVID-19 protocols. In Rwanda, services through SACCOs and other MFIs with rural outreach continued. For those FSPs still engaged in group lending, limiting the number of participants at group meetings or asking group leaders to attend instead of the whole group helped to ensure that rural borrowers continued to access financial services. Rural SACCOs in Rwanda witnessed an increase in demand for savings services.

| The main challenge for smallholder farmers was limited access to markets. This resulted in spoilage of produce, particularly during lockdowns, with the exception of Zambia where there was a partial lockdown. In general, the demand for loans from SHFs was suppressed due to reduction in demand for their produce since their end users, such as hotels, were not operating normally. On the ground, SHFs continued day-to-day activities, selling their produce to the limited accessible markets in the local communities. In Rwanda, SACCOs continued to trust SHFs but gave them smaller loans. |  |

ADECOR, a consumer association in Rwanda, highlighted that peoples’ saving practices during COVID-19 changed significantly. “For savings, people are saving more. Because of COVID-19, now they know the benefits of saving. So now when they get money, they do not use it immediately. They save saying that perhaps lockdown is coming again. Even those who don’t know how to save, now they’re trying to save. Even those dealing with SACCOs, even the poorest, because they have seen the consequences of not saving”. This resonated with findings from other countries, where precautionary savings increased by vulnerable populations.

|

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in an increase in precautionary savings as people became more aware of the importance of saving in safeguarding their money amidst economic uncertainty. This was because, as economic activities slowed down in response to COVID-19, many clients were forced to live off of their savings (Bikas FINCA Nepal - FinDev Interview April 2021). |

4.5 SUMMARY: IMPACT OF SHIFT TO NON-F2F DELIVERY CHANNELS ON FINANCIAL INCLUSION OF EXCLUDED GROUPS

The shift to non-F2F channels offered the possibility of: (a) reaching out to hitherto financially excluded customer segments, such as women and smallholder farmers in remote areas; and (b) lowering costs of delivery, making it easier for the FSPs to take on potentially less profitable customers from vulnerable groups. In practice, however, FSPs have not yet capitalized on the potential to expand outreach to these groups, at least not in the short term.

While FSPs are keen to retain and expand their customer base, low digital and financial literacy among the financially excluded groups is hindering the FSPs’ expansion to these groups. On the other hand, the shift to non-F2F channels may increase the FSPs’ reach to the financially excluded groups in future,as many FSPs interviewed said that they would continue with the shift to non-F2F digital delivery as a long-term business strategy.

5. Supervisory Risks From Shift To Non-F2F Delivery Channels

FSPs’ changes to their delivery channels aimed to maintain “last mile” access and provide financial services to their clients in innovative ways. However, these innovations may result in the emergence of new risks in the financial sector that may not have been prominent on the financial supervisors’ radar, or FSPs’ exposure to existing risks may increase. The study sought to establish which of the supervisory risks changed and heightened due to FSPs’ adaptations in their delivery models.

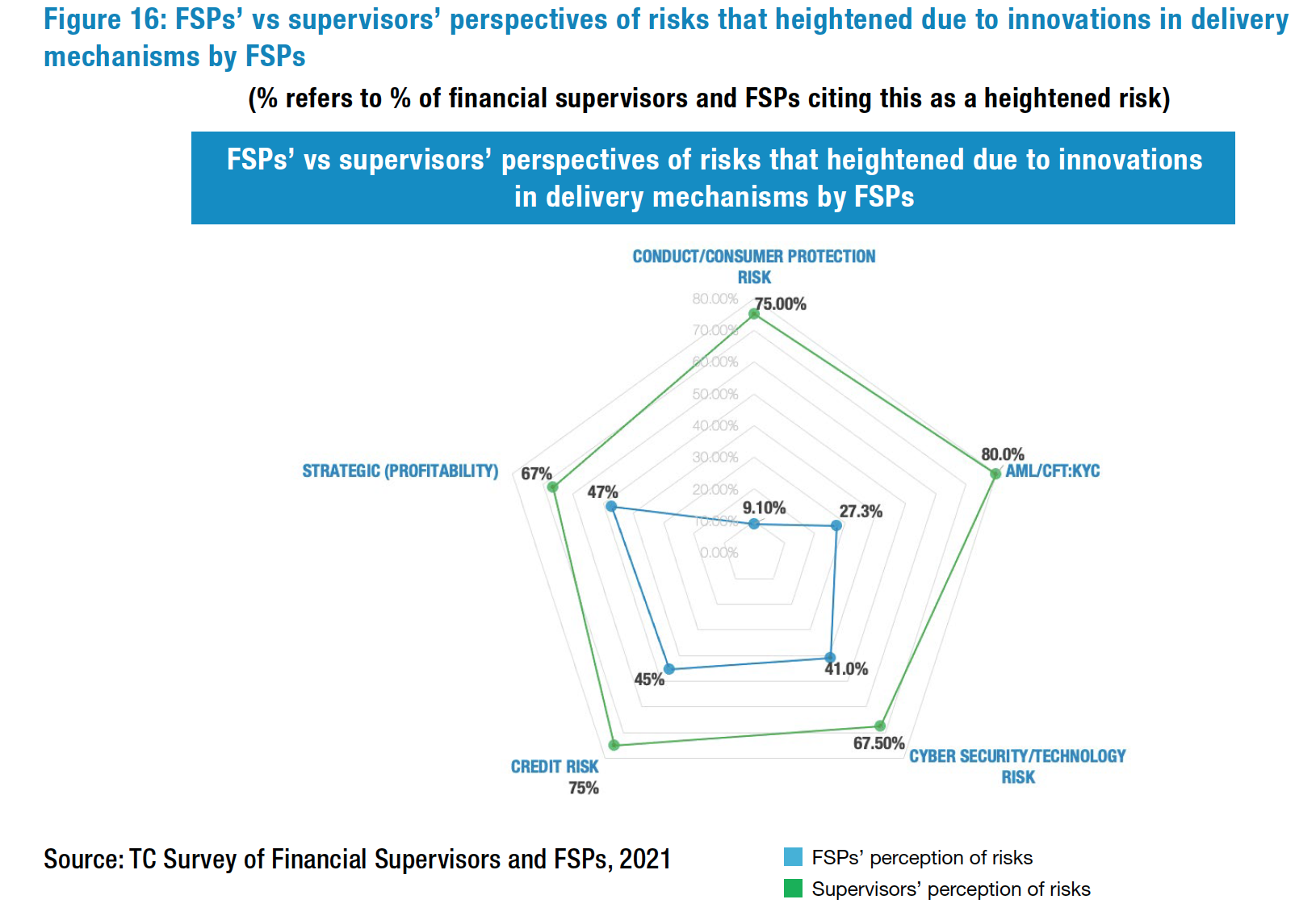

Survey results showed that perceptions of risks that have heightened due to shifts in delivery channels during COVID-19 differed between financial supervisors and FSPs. As depicted in Figure 16 below, financial supervisors ranked the top three risks as: anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism risk (AML/CFT), including KYC risk (cited by 80% of financial supervisors); credit risk (75%); and conduct risk and consumer protection concerns (75%). In contrast, the FSPs ranked their top three risks during COVID-19 as: strategic (profitability) risk (47%); credit risk (45%); and cybersecurity and technology risk (41%). Although strategic risk was not part of the top three for financial supervisors (cited by 67% of supervisors), it was closely trailing behind cybersecurity risk, which scored 67.5%. Nevertheless, as depicted in Figure 16 below, there is some overlap on the key risks between financial supervisors and FSPs, although their ranking of these risks may differ.

Credit risk was ranked one of the top three heightened risks during COVID-19 by both financial supervisors and FSPs, and this resonates with studies elsewhere. According to BIS (Carstens, 2020), credit risk is the first risk that was cited as having increased due to the impact of COVID-19 on economies globally. The one major risk cited by Carstens (2020) but not prioritized by financial supervisors surveyed in the study was liquidity risk, which was expected to rise due to pressure on FSPs’ liquidity as a result of increased client withdrawals at a time when client repayments were not flowing through.

The differences in risk perceptions between financial supervisors and FSPs are somewhat expected. Supervisors focus on financial stability, systemic risk and financial crime issues and prioritized risks such as AML/CFT, while FSPs focused on business goals prioritized strategic risks. Furthermore, when considering country-disaggregated data, it was clear that the supervisory authorities that had taken a proactive approach to discussing the emerging financial sector risks due to COVID-19, with their FSPs had a somewhat aligned risk prioritization. For example, at the start of the pandemic, the National Bank of Rwanda interacted with chief executive officers of FSPs and discussed the risks that were likely to increase and how the sector should respond. This not only aligned the two parties on the assessment of emerging risks in the financial sector, but enabled them to have a unified approach to risk mitigation strategies. Therefore, the difference in risk perceptions suggest there is room for financial supervisors to communicate their risk assessments and supervisory expectations to FSPs, particularly with respect to FSPs’ management of AML/CFT, credit, and conduct risks.

5.1 SUPERVISORY RISKS THAT HEIGHTENED DUE TO SHIFT TO NON-F2F DELIVERY CHANNELS

The section below discusses the key risks identified by both financial supervisors and FSPs that heightened due to innovations in delivery mechanisms by FSPs, starting with the risks prioritized by financial supervisors.

5.1.1 AML/CFT RISK

Financial supervisors ranked AML/CFT, including KYC risk, to have heightened the most as this risk was likely to affect all types of financial service providers, such as banks, fund managers, brokers, insurers, MFIs, and building societies. The survey showed a gap in the perception of AML/CFT risk between the financial supervisors and the FSPs, suggesting that supervisors may have to engage FSPs more on the potential risks with the shift to non-F2F delivery of financial services. 80% of supervisors rated KYC risk to have heightened due to the use of digital solutions by FSPs. Supervisors were rightly concerned that the submission of documents through electronic ways could result in challenges relating to verification of identity and increased AML/CFT risks. FSPs did not rate this risk that high, with only 27% of respondent FSPs saying that this risk heightened due to their innovations in delivery mechanisms. Those that felt that AML/CFT and KYC risks had heightened indicated that this was because high transaction limits “have led to high exposure on customer wallets with several incidences of fraud reported”, as noted by one FSP, and that when KYC processes are not done F2F, the risk of impersonation is heightened.

Policies put in place in the three countries prior to the pandemic helped the FSPs deal with the transition to receive KYC documents digitally. Firstly, even before COVID-19, as part of the proportionality principle all three countries were using ‘tiered KYC’, with simplified KYC allowed for the opening of basic accounts. These basic accounts were assessed to pose lower AML/CFT risk in that they would be limited in terms of value and type of transaction. Secondly, FSPs were expected to find ways of complementing online KYC documentation with other means of authentication. For example, Zambia passed a law, The Electronic Communications and Transactions Act, 2021, [21] which provided the legal framework for secure electronic signatures.

When the pandemic began, these pre-existing rules on simplified KYC practices helped to set the parameters that enabled FSPs to manage this AML/CFT risk with non-F2F delivery of financial services. In Rwanda, the supervisors expected FSPs to use a multifactor authentication process to ensure that the digitally communicated documents or signatures were properly verified.

5.1.2 CONDUCT RISK AND CONSUMER PROTECTION CONCERNS

Figure 16 above shows that 75% of financial supervisors believed that conduct risk and consumer protection concerns had heightened due to innovations in delivery mechanisms by FSPs. Their view was that FSP staff needed to ensure that the products were suitable for the clients who are purchasing them. They noted that the challenges were compounded by clients’ lack of understanding of these products due to limited financial literacy.

In contrast, most respondent FSPs felt that conduct risk had not changed due to their innovations in delivery mechanisms, as conduct rules are still enforced and normal conduct procedures still apply. Only 9% of respondent FSPs felt that this risk had heightened. The few FSPs who cited this risk highlighted that the introduction of remote work shifts and digital platforms for business increased conduct risk as staff could take advantage of the adaptations and use work time and electronic channels to conduct personal errands. As a result, they might fail to meet set business targets and at the same time compromise the customer experience, leading to reputational risk. Some FSPs felt that there is now an increased need for consumer protection, given that communications and Financial supervisors and FSPs alike in all three countries echoed the need for greater efforts on digital and financial literacy, and the authorities had already launched financial literacy campaigns before COVID-19. However, the financial supervisors noted the need to continue and enhance such campaigns to ensure effective outreach to the vulnerable customer groups that require this the most. ‘Digital literacy’, which was not the major thrust of pre-COVID financial literacy programs, may now need to be prioritized to enable excluded groups to access financial services through non-F2F channels.

5.1.3 CYBERSECURITY AND TECHNOLOGY RISK

Two-thirds of respondent financial supervisors indicated that this risk has heightened due to innovations in delivery mechanisms by FSPs. Their sense was that as FSPs rely more on information technology (IT) systems offering digital solutions, their exposure to IT risks increases. Cybersecurity risk was also identified in BIS (2020) as heightened due to the increased use of digital products. In Zambia, the Competition & Consumer Protection Commission (CCPC) reported an increase in the number of complaints related to digital finance scams.

|

Compared to financial supervisors, a lower proportion of FSPs (41%) believed that cybersecurity risk has increased. They noted that the increased risk was due to access to core banking systems offsite using VPN, additional remote access, and limited physical and technical controls of FSPs’ data centre in the remote working environment. Furthermore, the risk of hacking and more phishing emails coming into the work setup increased, with more remote access used by FSPs and with reliance on third party IT integration. FSPs were also concerned with the likelihood of passcode exposure. Client email accounts can be cloned and their data compromised. Medium sized banks in Rwanda and Zambia, however, indicated that they have platforms that monitor incidents of cybersecurity breaches and, so far, no incidents have been identified.

The increase in technology risk was deemed to have stemmed mainly from increased risk of failure in technology; for example, power outages, network failures, and increase in channels have led to a higher risk of cybercrimes. Furthermore, technological applications were becoming an imperative rather than an option for FSPs, increasing their exposure to technology risk. Integrating legacy IT systems has also increased risk; for example, integrating FSPs’ payment systems to core banking applications. Some FSP staff were reported to have faced adaptability problems in the use of technology, increasing the risk of human error, and operational risk when interfacing with these IT systems.

In response, all three countries are developing or reviewing their cybersecurity laws. Sierra Leone and Zambia are developing legislation. Rwanda is reviewing the current legislation and is considering increasing the use of non-F2F and digital delivery of financial services. From a consumer perspective, digital literacy, and not only financial literacy, was becoming a key concern for supervisors. For example, a consumer association in Rwanda indicated how the lack of consumer knowledge of digital delivery of financial services meant that unsuspecting clients were falling prey to unscrupulous agents, who would transfer funds to their own accounts instead of to the intended beneficiaries. Such incidences might be curtailed if clients were more digitally literate.

5.1.4 CREDIT RISK

75% of respondent financial supervisors felt that credit risk has heightened, largely driven by FSPs offering digital loans, which they consider risky as screening borrowers may be difficult. The default rate on such loans was reported to have increased.

| 45% of respondent FSPs felt that credit risk had heightened, albeit not necessarily due to changes they made in delivery channels but rather due to the depressed business environment. This decreased customers’ capacity to pay, resulting in increased defaults. Some indicated that they had to restructure parts of their loan books and increase loan loss provisions, while other FSPs resorted to conducting daily monitoring, calling defaulting clients, and entering into agreements to allow borrowers a grace period. |  |

Some FSPs in Sierra Leone felt that, due to COVID-19, relaxation of client screening processes, lack of sufficient on-site monitoring precipitated the increase in loan defaults.

5.1.5 STRATEGIC AND PROFITABILITY RISK

67% of respondent financial supervisors felt that this risk had increased, and some linked this risk to technology risk; that is, whether FSPs were able to make the strategic transition during COVID-19 or not. Most FSPs were now embarking on digital delivery channels for survival and were forced to accelerate digital transformation programs that may have been scheduled for the future. Restructuring operations, raising capital, and securing resources (both staffing and skills) in this area could affect their strategic positioning. In some ways, some FSPs had to reorganize their funding to prioritize capital expenditures to strengthen core banking systems as well as to tap into current applications that would allow digital transactions.

47% of respondent FSPs were of the view that strategic and profitability risk heightened due to increased non-performing loans (NPLs), increased loan loss provisions, payment holidays granted to clients, reduced insurance uptake against rising cost, slower economic growth, and a challenging operating environment for customers. Furthermore, the increase in operational expenses to manage the impact of the pandemic reduced profitability significantly; for example, installing IT software and ensuring all staff were connected remotely (on Zoom or Microsoft Teams) or onto core banking systems. One FSP from Zambia explained how they had partly halted business operations at the onset of COVID-19, thereby affecting their profitability targets. Another FSP in Sierra Leone explained that the initial reaction for most FSPs was to stop new disbursements, which in turn affected the growth of their assets and consequently affected profitability.

The only other risk that was not prioritized but which had been anticipated to increase at the onset of COVID-19 was liquidity risk. In Rwanda and Zambia, financial supervisors and FSPs alike assessed this risk to be well managed as COVID-19 recovery funds were set up to cushion FSPs and ensure that there was sufficient liquidity on the market. In both countries, these funds were not exhausted by the time of this study.

5.2 SUMMARY: RISK PERCEPTIONS OF FINANCIAL SUPERVISORS AND FSPS

The shift from F2F to non-F2F delivery accentuates certain risks in the FSPs’ business models that financial supervisors must closely supervise. The main risks are AML/CFT, operational, and cybersecurity. While FSPs are aware of these risks, they are also concerned about strategic risks and profitability in the economic downturn caused by COVID-19.

Supervisors are also aware that they need to enhance their supervision of FSPs’ technologically-driven techniques as transactions become more digitally driven. Financial supervision will have to adapt. As one financial supervisor explained; “I see this as an opportunity to reinvent the way services have been delivered, putting customer service at the forefront, convenience and things like that, but at the same time, tightening controls to ensure that we’re not opening up a can of worms. My hope is that it spurs innovation for improved service delivery going forward”. Off-site supervision became the only option, especially during lockdowns. For Zambia this has precipitated the use of electronic submissions of reports to the supervisors with electronic data warehousing at the authority, making the supervisors’ investments in their own IT and information-gathering capacity a priority.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1 CONCLUSIONS

FSPs across the three countries adapted their financial services delivery channels in response to COVID-19 to different extents.

Sierra Leone, which was less affected by COVID-19, retained most of the F2F delivery but maintained strict COVID-19 health protocols.

Zambia relied more on the use of agents in limited F2F delivery and also used digital delivery, such as mobile banking.

Rwanda, in line with national efforts to go cashless, switched mostly to non-F2F delivery through mobile and internet banking. phone and internet banking.

The shift from F2F to non-F2F was mostly to digital means, and the speed and ease with which FSPs could switch depended on:

The current state of national infrastructure, such mobile and internet networks in the country; for example, the prevalence of USSD codes and mobile phone penetration;

FSPs’ own strategic investment in this area pre-COVID, which was accelerated during the pandemic; and

Supportive policies by financial supervisors, in partnership with national authorities, for example, the policy of ‘zero charge’ on mobile transactions in Rwanda and the regulatory sandboxes in Zambia.

The move from F2F to non-F2F delivery accentuates certain risks in the FSPs’ business models that financial supervisors have to closely monitor and manage in the financial system. The main ones are AML/CFT, operational, and cybersecurity risks. FSPs are aware of these risks, but they are also concerned with strategic risks and reduced profitability amidst heightened credit risks in the economic downturn caused by COVID-19.

So far during the pandemic FSPs have not yet capitalized on the potential to expand outreach to financially excluded groups – at least not in the near term. Although the move to non-F2F channels offered the possibility of reaching out to financially excluded customer segments such as women and smallholder farmers in remote areas, and lowering costs of delivery, thereby making it easier for the FSPs to take on potentially less profitable customers from excluded groups, in practice this potential remains latent. Two major barriers exist: a) digital financial literacy of the potential customers (demand side; and b) lack of trust in digital delivery of financial services.

6.2 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FINANCIAL SUPERVISORS

The recommendations presented here for financial supervisors are structured around their mandates in financial stability and inclusion. While there may be some apparent tension between these two mandates, there are specific actions that enable financial supervisors to meet financial inclusion objectives on the basis of sound management of prudential risks in FSPs and overall financial stability.

Prudential objectives and financial stability

Financial supervisors should closely supervise the emerging risks in FSPs arising from the accelerated shift to non-F2F services delivery. Financial supervisors should consider:

a. Increasing communication and sharing the supervisor’s risk assessment of emerging risks (AML/CFT, operational, cybersecurity, etc.) during COVID-19 with FSPs.

b. Clearly setting out supervisory expectations to FSPs through rules or best practices guidelines on the enhanced risk management measures that FSPs should take to ramp up non-F2F delivery of financial services during the pandemic.

Examples of areas for best practices guidelines include:

- AML/CFT risk: where KYC documents are taken in non-F2F transactions (a more common practice during COVID-19), setting out rules and guidance required in FSPs to mitigate AML/CFT risks (for example, requirement for multifactor authentication for KYC).

- Operational risk: setting out supervisory expectations of how FSPs should manage increased reliance on outsourcing of key processes, such as customer onboarding to agents who are not employees of the FSPs. While use of agents is generally provided for in the previous laws, care should be taken to ensure the accompanying regulations keep pace with the changes to functions outsourced by FSPs to the agents during COVID-19.

- Cybersecurity risks: reviewing cybersecurity rules on FSPs to keep pace with the increased digitalization of FSPs’ operations. This process is already underway in Rwanda and Zambia.

These guidelines should be supplemented by thematic reviews or inspections of FSPs on these emerging risks.

c. Enhancing information gathering for effective supervision of these delivery channels. Financial supervisors will need to be confident that they know what delivery channels FSPs are using during COVID-19, and whether the information they currently require from FSPs allow them to make a risk assessment of these delivery channels. Given that it may be difficult to conduct onsite inspections during the pandemic, financial supervisors will have to invest more in digital data collection, analysis, and use. While the use of supervisory technology and regulatory technology (SupTech and RegTech) is still nascent in the three countries, financial supervisors highlighted this investment to be imperative.

Financial inclusion

Even while keeping a close eye on the risks, financial supervisors with financial inclusion mandates can still support the potential offered by the shift to non-F2F delivery by FSPs to reach out to financially excluded groups, who most need support in the economic downturn during the pandemic. Support from financial supervisors for national digital financial literacy efforts can yield financial inclusion dividends in the long term as FSPs shift towards digital service delivery. In particular, financial supervisors should consider:

a. Working with other stakeholders on digital financial literacy: the more financially literate consumers are, the better for financial inclusion and for the stability of the whole system and the use of innovative methods, such as the ‘digital ambassadors’ in Rwanda;

b. Elaborating supervisory expectations on risk-based KYC for FSPs that facilitate the onboarding of financially excluded groups as customers in the formal financial system through simpler KYC requirements for these customers that pose low risk;